I had a meeting once with Howard Marks, who I had wanted to meet for a long time. He’s a famous bond investor that does a lot of writing. For 15 minutes he asked me questions about the venture industry, a lot of structural questions, and I answered him as best I could.

He said, “That’s a really shitty industry”. I said, “Why do you say that, what do you mean?”, and he said “Cyclical collapse is built into the structure.”

Bill Gurley on his conversation with Howard Marks, All In Summit, May 2022

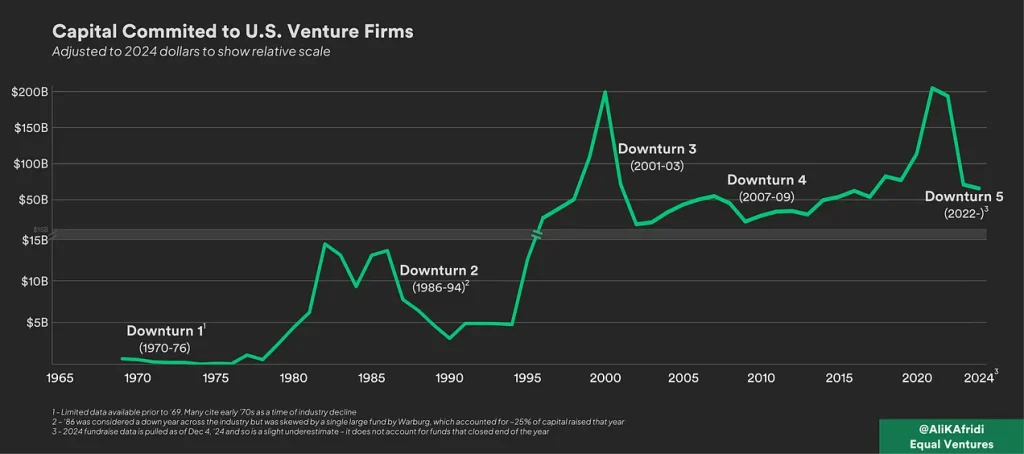

‘2024’ could have been a short chapter in the history of venture capital. Another post-boom year of declining deal activity, recovering valuations, recaps and shutdowns. We left it with the public markets looking healthy and hope that IPOs might reappear on the horizon. All good reasons to flip the page to 2025.

Before you move on from 2024 entirely, consider the boiling frog. Venture capital has been quietly outgrowing traditional definitions over the last 15 years. Last year, as AI drove heat into a cool market, the cracks started to appear.

The venture capital industry has historically worked as a relay race where investors at one stage bring in the next stage of investors to fund and support companies as they scale. Right now, it feels like AI investing breaks this model in a few important ways.

Charles Hudson, Managing Partner at Precursor Ventures

This isn’t just about inflated valuations, overcapitalisation and ZIRP. It’s about the effort of a few firms to outgrow the boom-and-bust nature of venture capital through a new model for investing.

Consider the well documented rivalry between Andreessen Horowitz and Benchmark, with their opposing views on capital abundance in venture.

Bill Gurley declined my requests for comment, but he has publicly bemoaned all the money that firms such as a16z are pumping into the system at a time when he and many other V.C.s worry that the tech sector is experiencing another bubble. So many investors from outside the Valley want in on the startup world that valuations have been soaring: last year, thirty-eight U.S. startups received billion-dollar valuations, twenty-three more than in 2013. Many V.C.s have told their companies to raise as much money as possible now, to have a buffer against a crash.

“The Mind of Marc Andreessen“, by Tad Friend

Benchmark has set the standard for “traditional” venture capital, managing small and efficient funds, close relationships with founders, and exemplary returns. In contrast, Andreessen Horowitz represents the era of ‘capital of a competitive advantage’; a confluence of hyper-scalable SaaS, digital growth channels, and historically low interest rates. Not merely a competing venture strategy, but the emergence of a fundamentally new product that trades efficiency for scale.

The divergence of Andreessen Horowitz (and a few similar firms) from the traditional playbook has created some confusion, as greener GPs attempted to emulate aspects of both. Lacking either the AUM of Andreessen Horowitz or the discipline of Benchmark, they inevitably hit the slippery slope of badly managed risk. This can also be seen in the muddled logic on topics like entry multiples, valuation and concentration, where the ‘common wisdom’ has often made little practical sense.

Fortunately, there is light at the end of the tunnel: As this new product is better understood by LPs, GPs and founders, the chaos is better controlled: LPs will have more realistic return expectations, benchmarks and timelines. GPs will be able to identify coherent strategies and compatible advice. Founders will have a clearer choice between traditional venture capital, and the new model of “venture bank”, and the expectations associated with each.

Too Big to Fail

In 2009, with the launch of their first fund, Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen slipped into the role of VC brilliantly. They had strong opinions about capital efficiency and portfolio structure, a level of sophistication that surpasses many of today’s GPs.

Despite the success of that first outing, capturing huge outcomes like Skype, the market soon presented a new opportunity. In 2010, rebounding from the GFC, incumbent firms were raising funds in excess of $1B—a throwback to the dotcom exuberance that Benchmark had criticised. Institutional money was once again on the hunt for new opportunities and software had begun ‘eating the world’.

As entrepreneurs (another contrast to Gurley) Horowitz and Andreessen felt no loyalty to the traditional playbook. They saw an opportunity to innovate; the chance to build a scalable model for venture capital and take a dominant position. So, they invested heavily in media to build a ‘household name’ brand. They sought network effects by launching scouts programs and accelerators. Platform teams were assembled to handle their growing portfolio. Rather than an investment team, they built something more like a sales force. Essentially, they exploited a “boom loop”: raising money to maximise exposure, manufacture category winners, distribute healthy markups and raise more capital. In this environment, venture capital became a cutthroat zero-sum game with very little discipline.

Some of the VCs who funded predation succeeded spectacularly, and the basic incentives of venture investing that tempt VCs to employ this strategy persist. The goal of antitrust law is to push businesses away from socially costly anticompetitive behavior and towards developing socially valuable efficiencies and innovations. We think that Silicon Valley could use a nudge in that direction.

“Venture Predation“, by Matthew T. Wansley & Samuel N. Weinstein

Jump to mid-2022, and the post-ZIRP hangover experienced by the venture market. Almost everyone had gotten caught-up during the decade of near-zero interest rates capped off by pandemic-driven irrationality (except Gurley, who had stepped back from Benchmark in 2020). The critics of the Andreessen Horowitz model began to emerge, pointing to their inflated check sizes and irrational pursuit of “Web3.0”. Now, like everyone else, Andreessen Horowitz would surely suffer from falling returns and backlash from LPs?

It happens that Andreessen Horowitz raised more than $14B in new funds during the first half of 2022, close to the combined total of their funds raised in the preceding three years. They were well prepared for the fundraising winter of 2023, a year which many large firms used to rebalance their portfolios through secondary transactions—playing on the extreme heat around companies like OpenAI, SpaceX and Anduril.

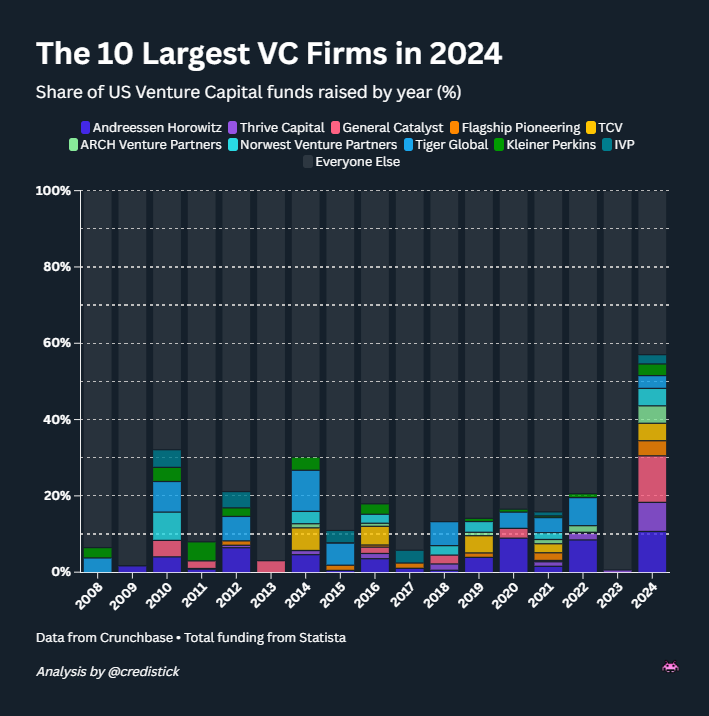

In 2024, as the slump continued (down roughly 50% from the funds raised by VCs in 2020 and 2021) Andreessen Horowitz came back and raised another $7B. In fact, the 10 largest venture banks raised more than half of all venture dollars last year. The firms that had contributed most to the collapse were suffering from it the least. How could this be? The outcome frustrated many smaller GPs who had been squeezed out of deals and were having a harder time closing funds.

Plans Measured in Decades

If you want to build a venture bank, you need billions of dollars on a regular basis, and it needs to be truly patient capital. Not high-net-worths, not family offices, perhaps only the largest pension funds and endowments. Most of all, you need sovereign wealth.

This transition away from venture capital’s traditional LP base was the central gambit of venture banks. With performance stabilised by the scale of their AUM, the ability to extend into other assets and an internationally recognised brand, they are able to court some of the world’s largest pools of capital. Rather than hunting alpha, they farm ‘innovation beta’—indexing across as much of the fast-growing tech market as possible, with exposure to every hot theme, at every stage, both private, public and tokenised.

A lot of the detail is lost when you’re operating at that altitude. Valuation, consensus, discipline, markets… they all matter less if you’ve escaped the typical venture capital fund cycles. Liquidity can be delivered through the secondary market, continuation funds, distributions of public stock or sales of crypto holdings. If it’s a tough market for IPOs, you have the scope to wait it out. When there’s a ‘liquidity window’, like 2021, you can jettison as much as possible—as quickly as possible.

If success in venture capital is primarily about being in the right place, at the right time, the proposition of venture banks is to be everywhere, all the time.

Our results suggest that the early success of VC firms depends almost entirely on having been “in the right place at the right time”—that is, investing in industries and in regions that did particularly well in a given year.

“The persistent effect of initial success“, by Ramana Nanda, Sampsa Samila and Olav Sorenson

There is also opportunity in this bifurcation for GPs at traditional firms. While venture banks smother consensus themes, they do so on behalf of this new class of supersized LP. For everyone else, there should be less competition in the traditional LP base—once they recover their enthusiasm for the asset class.

The shift obliges smaller firms to focus on non-consensus themes—which they should have been doing all along. Access to ‘hot deals’ is no longer a core proposition for LPs, as it becomes clearer that the juice isn’t worth the squeeze. Instead, GPs should focus on evergreen investing theory. This includes portfolios structured to optimise for outliers and manage risk and a sourcing process that minimises bias, or what Joe Milam calls “Process Alpha”.

The conventional venture model relied on the power law to rationalize overly concentrated portfolios and “hot deal chasing” when basic portfolio management theory emphasizes (non-systematic) risk management through diversification.

“How to Construct and Manage Optimized Venture Portfolios“, by Joe Milam

Essentially, venture capital goes back to being a positive-sum game that effectively finances innovation, and looks less like a ponzi scheme.

A number of other positive consequences could emerge from this correction:

In moving away from consensus themes, VCs will be forced to develop an approach to understanding the value in novel propositions.

So much funding in the valley has rushed towards the consumer, at the expense of what we would argue are more significant projects.

Nicholas Zamiska, Office of the CEO, Palantir

Some of that shift has been cultural, but much is simply that the pervasive practice of pricing with ARR multiples has favoured well-understood segments over the last decade. Deep tech and hardware suffered because VCs simply weren’t sure how to put a price tag on those companies.

Calculating or qualifying potential valuation using the simplistic and crude tool of a revenue multiple (also known as the price/revenue or price/sales ratio) was quite trendy back during the Internet bubble of the late 1990s. Perhaps it is not peculiar that our good friend the price/revenue ratio is back in vogue. But investors and analysts beware; this is a remarkably dangerous technique, because all revenues are not created equal.

Bill Gurley, GP at Benchmark

As VCs develop a keener and more independent sense for value, the exit pipeline begins to look a lot healthier. Metrics that look at financial health in addition to sheer growth of revenue will more effectively align companies with the expectations of both public market investors and prospective acquirers. Like the old days of venture, much of growth and prosperity will be available for mass market retail participation — which is great for the ‘soft power’ of tech.

Some of the world’s most highly valued public tech companies entered the public markets with quite modest valuations, at least by today’s standards. Microsoft, Amazon, Oracle and Cisco all debuted with market caps south of $1 billion. Of those, only Microsoft topped $500 million. This translated to relatively modest gains for their private market investors, compared to the massive value appreciation they have all experienced post-IPO.

“Who’s reaping the gains from the rise of unicorns?“, by Adley Bowden

On the other hand, venture banks who have developed monster companies like OpenAI, SpaceX and Anduril, will be able to keep tapping into this expanded pool of private market capital via secondaries. Where companies are strategically sensitive, particularly in the realms of AI or defense, this may be seen as preferable to public company disclosure requirements or the threat from activist shareholders.

Secondary markets also represent an opportunity for traditional venture capital. As managers pick up better standards for valuation, providing greater transparency and explainability, activity is bound to increase. This means more options for liquidity, more consistent buy-sell tension to keep prices under control, and participation from a more diverse base of investors. Finally, it also offers greater cap table flexibility to founders and early investors.

Let’s be realistic here; you’re better off in the fullness of time if certain players are in your cap table, and not a seed fund.

Mike Maples, Jr, Co-Founding Partner at Floodgate

Clarity Precedes Success

2025 should mark the end of confusion about venture banks and their role in the ecosystem. After a decade of increasingly confused standards and benchmarks for traditional VC, the two products have been neatly split by the wedge of AI.

This is an opportunity for rehabilitation, as the confusion around the change has created more issues than the change itself. Both sides are now able to lean into their strengths, consensus vs non-consensus, alpha vs beta, and deliver the commensurate returns to LPs with matched expectations.

Make no mistake, 2025 will be a crucible for venture capital. The divergence of exits from public market performance is worse than ever, and confidence is low. Despite this, there seems to be a resurgence of smaller firms raising capital—matching historical patterns where incumbents lead the rest of the market by a year.

Critically, how will smaller GPs execute in the new environment? Will they learn the lessons from the last five years and play to their strengths? Or will they keep trying to span the chasm of small fund risk tolerance and large fund risk appetite?

Leave a Reply