Why the most investible founders might have the least fundable ideas

“What do you look for? Grit — sure… everyone likes to say that… intelligence… obviously — the right balance of taking feedback & independence — sure. But you have to go deeper — have a deeper framework on really what makes for great founders who are going to stick it through and be winners AND what is the shorthand you can share with your partners / each other on WHY you as a lead investor actually believe in this person / the bet you are making.”

Sam Lessin, GP at Slow (Draft letter to LPs)

Four basic premises for early-stage investing:

- Non-consensus investments produce stronger returns

- Proactive origination strategies drive outperformance

- Founder attributes create antipatterns for investment

- Track record isn’t a reliable signal of future success

Accepting all of these means acknowledging that first-check VCs should generally source their own deals without relying heavily on signals like traction, market activity, or credentials.

This is the torturous reality of being the first money in: reaching conviction on little more than a story.

And you must be able to do that in a thoughtful manner that can be explained to others, and learned from in future.

A Complicated Package

The “jockey’s versus horses” debate goes back to the very beginnings of venture capital. It has also become painfully reductive: given a choice between markets, technologies or people, being explicitly pro-founder has the best optics.

Of course, it’s never that simple. All information is useful in the decision-making process, and each aspect tells you something valuable about the others.

- The approach described by Peter Thiel is to consider the whole pitch as “some kind of complicated package deal,” combining people, ideas and technology.

- Or, as Nabeel Hyatt puts it, the way to “separate hucksters who do a good pitch from people who are real executors is to look at the thing that comes out of their hands”.

- Indeed, Sam Altman described the Y Combinator screening process as looking closely at the “non-obvious brilliance of the idea” being presented.

Indeed, the problem a person chooses to solve, and how they approach solving it, can tell you a lot about the person..

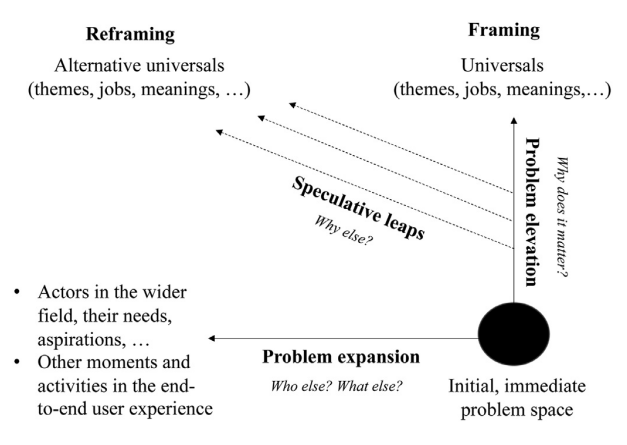

Another way to frame this is outlined by Mattia Bianchi and Roberto Verganti in “Entrepreneurs as Designers of Problems Worth Solving“:

“Finding meaningful problems to address is a critical driver of innovation and entrepreneurship in today’s turbulent environment, possibly even more so than problem solving.”

“Designing a problem is mainly based on inventively reframing a situation through its expansion, elevation, and prospective sensemaking. The outcome is a more meaningful problem when it aligns the entrepreneur’s purpose with how society, technology, and culture are changing.”

Entrepreneurs as designers of problems worth solving

Bianchi and Verganti’s suggestion is that the act of identifying important problems is itself indicative of potential, and a precursor to “designing problems”: the addition of novel aspects which weren’t part of the original problem scope.

problems

This process demonstrates that a founding team has a deep understanding of a particular problem (and the universe around it) and a novel and thoughtful solution.

Finding Outliers and Avoiding Hucksters

Understanding and evaluating qualitative traits is obviously very difficult, especially when the playbook of what VCs say they look for is now wide-open for study.

However, while there’s a strong canon of common wisdom about the attributes of “good founders”, very few VCs have build a framework for recognising, documenting and reflecting on them.

An example framework that overlaps with the “problem design” approach is the list of attributes used by 1517 Fund, as described in Michael Gibson’s book, ‘Paper Belt on Fire‘:

- Edge control

- Crawl-walk-run

- Hyperfluency

- Emotional depth & resilience

- Sustaining motivation

- The alpha-gamma tensive brilliance

- Egoless ambition

- Friday-night-Dyson-sphere

- Wily & wondrous

- Alchemy

(Descriptions and examples for the first 8 are included in the book. The final two may be included in a forthcoming update.)

If you study these attributes, and the story behind them, you will understand an important qualification: they reflect markers of outlier behavior. The intent is to seek out extraordinary people, rather than create template for ordinary brilliance.

Indeed, the industry’s more common reliance on gut-feel and credentials is likely to exclude outliers, and limits the potential for constructive reflection on (and true accountability for) investment decisions:

“For example, VCs often discuss the ‘chemistry’ between themselves and the entrepreneur. The deal often falls through if the chemistry is not right. Such intuitive, or “gut feel”, decision making is difficult to quantify or objectively analyze.

The added complexity from subjective information further clouds the decision making process and invites the decision maker toward more biases. Due to the complexity of the decision and the VCs’ intuitive approach, VCs may have a difficult time introspecting about their decision process. In other words, VCs do not have a comprehensive understanding of how they make the decision.”

A lack of insight: do venture capitalists really understand their own decision process?

There are two typical outcomes of this laziness:

- Investors resort to simple patterns in their understanding of founder potential, falling prey to exactly what Kahneman describes in The Hazards of Confidence, and producing predictably worse outcomes.

- In the absence of an objective process, the analysis of founder potential is displaced by homophily, where investor ego equates “high potential” with “similar to myself” across everything from facial features to political beliefs.

Instead, the best way to understand something like determination or clarity might be to look for founders with a well-designed problem. For example, making humanity multi-planetary, making energy too cheap to meter, tapping atmospheric rivers, or building the telescope for drug discovery.

- If a founder has designed a problem which seems high on importance and low on popularity with investors, they’re likely in it for the right reasons.

- If they can articulate the problem in a novel and coherent manner then there’s a good chance they’ll be able to find a solution where others will fail.

- If the story of that “problem design” process feels deeply personal (it keeps them awake at night, and busy on weekends) there’s a good chance they will persevere.

- If their approach to the problem shows a willingness to go back to basics and do the work to learn whatever is required, they likely have the agency required for entrepreneurship.

It doesn’t matter if the founder ends up pivoting. That may even be desirable. It doesn’t alter the value of what you can learn from their approach to designing and solving problems.

Thus, some of the least obviously “fundable” ideas may be the most deserving of investment, if you use the right lens. Investors should seek founders that have picked good quests over those that choose lower friction.

Conspicuous Consumption

At the opposite end of this spectrum are rage bait startups and the blight of limbic capitalism.

It is no coincidence that these companies are always at the dead-centre of consensus. The playbook is simple:

- Build in a competitive category

- Pursue viral stunts that make you unignorable

- Raise a huge round to fund more virality / growth

This exploit a basic premise of scaled venture capital: the largest firms cannot afford to miss potential winners.

A startup can look like a potential winner by having a track record of success, a density of technical talent, or by commanding enough attention to become an object of desire; the ‘conspicuous consumption‘ of venture activity.

As long as they pass one of these legibility tests, they get onto the treadmill of “tier-1 VC” convention bidding where success is hitting milestones to earn staying on the treadmill. Capital feeds growth on hype-adjusted multiples, producing fuzzy venture math which is capable of any conclusion you desire.

The only problem these companies truly solve is scaled capital allocation and systematic AUM growth for venture capital firms. The founder becomes a minor player in a largely commensal relationship designed to support the VC’s ambitions.

“The hyper-normative world of consensus-seeking is dripping with incentives that would make you their slave. And if you don’t have anything, in particular, that you believe, then they will likely succeed.”

Build What’s Fundable

Fund Good Quests

Without revisiting the topic of bifurcation yet again, it is clear that one of the models described above works for traditional VCs, while the other is geared toward the scaled allocators.

So, if you are an early stage investor, one of the best things you can ask yourself in the early stages of evaluating a company is whether the founders are designers of a problem worth solving.

It may not lead you to companies that grow rapidly, which may make raising your next fund more of a challenge. But, like proper risk management, it’s the right approach if you really care about maximising returns and building a durable legacy as a venture investor.

(top image: “Astronomer Copernicus“/ “Conversations with God”, by Jan Matejko)

Leave a Reply