The danger of inherited biases in VC LLM applications

There’s a fascinating history of research comparing venture capital decisions to algorithmic outcomes. In a basic sense, these studies pitch human judgement against machine scoring systems.

What’s particularly interesting about these studies (detailed below) is the clarity they provide about our vulnerability to cognitive biases. Where investors are able to reason objectively, they comfortably outperform algorithms. Where they can’t, they are soundly beaten.

This topic is increasingly relevant, as more studies are released looking at the use of LLMs in the venture capital decision making process (also detailed below).

The main point I will explore here is that humans represent one end of a spectrum (hyper qualitative), and algorithms represent the other (hyper quantitative), and LLMs land somewhere else entirely: they offer powerful automation, but have inherited our very human biases.

There are also important points related to the GP:LP interface and the relationship-based nature of venture capital, which are both connected to the question of why venture capitalists have resisted these findings so far.

Not Better, Not Worse, But Different

Fittingly titled, Predictably Bad Investments by Diag Davenport covers the basic sin of pattern matching. Looking at a sample of 16,000 startups, and comparing real-world outcomes versus the output of an algorithm, the study finds that bad investment decisions are typically a product of over-indexing on founder attributes (particularly “star power” and charisma) and under-indexing on the idea itself.

This theme appears again in Machine Learning About Venture Capital Choices by Victor Lyonnet and Léa H. Stern, where again venture capital outcomes are compared to algorithmic choices. This study goes beyond venture-backed companies, using government data for a perspective on missed opportunities. The conclusion is that not only do venture capitalists make predictably bad investments, they also miss predictably good ones by overweighting “great founder”stereotypes.

These papers bear important consequences for venture capital, but are ignored for an uncomfortable truth they reveal: the common industry wisdom about picking founders doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

The real answer is a little more complicated. To help complete the picture, we can turn to Do Algorithms Make Better — and Fairer — Investments Than Angel Investors? by Torben Antretter, Ivo Blohm, Charlotta Sirén and Dietmar Grichnik. Here, the authors compare the performance of human investors against an algorithm once again. Importantly, they don’t simply look for a winner, but an understanding of who wins, and why.

Once again, the study found that an algorithm broadly outperformed human investors, producing an IRR of 7.26%, versus an average of 2.56% from the 255 angel investors. However, humans still came out on top by a wide margin, with experienced investors who showed negligible signs of cognitive bias producing an average IRR of 22.75%. Crucially, it was the lack of bias rather than the experience which drove that outperformance; experienced investors with clear signs of bias produced a fairly pathetic 2.87% IRR.

Combining the three papers, we can drill further into the conclusion: algorithms outperform most human investors because an algorithm cannot be swayed by charisma, it does not care if you went to the same university, if you live in the same area, have similar facial features or matched political beliefs. Investors who wish to fall into the high-performing category must master these cognitive biases, to reduce the drag they produce on investment performance.

Another perspective on this question can be found in And the Children Shall Lead: Gender Diversity and Performance in Venture Capital by Paul Gompers and Sophie Wang. This study examined the make-up of venture capital investment teams, finding that diversity is positively related to returns when it is the result of the firm recognising and controlling the same cognitive biases. If there’s institutional clarity about objectively recognising talent, it will reflect through the whole system.

Best Served Cold

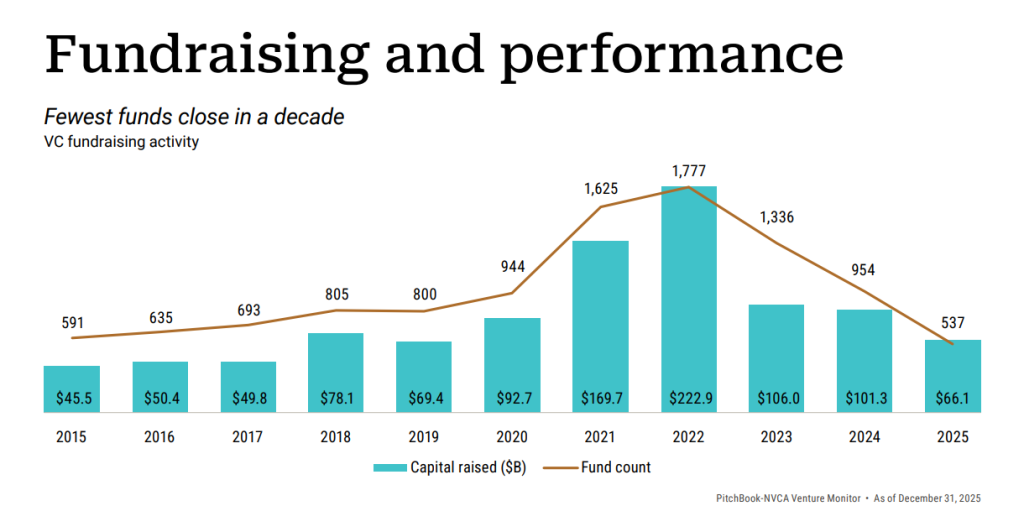

As a fundamentally illiquid strategy, studies on venture capital investment behaviour must address the question of cycles. How do these conclusions change if the market hits a bump, versus periods of sustained growth?

In the cases of investor biases, and the over-reliance on subjective founder attributes, we can turn to Venture Capitalists’ Decision-Making Under Changing Resource Availability: Exploring the Use of Evaluative Selection Criteria by Noah John Pettit. Unsurprisingly, the study finds that investors in “hot markets” tend to lean further into faster subjective judgements (i.e. more System 1 Thinking) as the possibility of failure seems remote in periods of abundance. Implicitly, this amplifies the issues described above, relating to cognitive biases and founder attributes.

This finding is reproduced in Venture Capitalists’ Decision-Making in Hot and Cold Markets: The Effect of Signals and Cheap Talk, by Simon Kleinert and Marie Hildebrand. Not only do venture capitalists rely more on “cheap talk” (e.g. promises of rapid growth) from charismatic founders in hot markets, but the Fear of Missing Out leads them to neglect more useful but costly analysis. Mirroring the studies above, venture capitalists end up relying on predictably poor information, and ignoring predictably useful information.

Amongst a host of other adverse incentives, this FOMO-driven laziness helps drive hot markets into the typically spectacular end-of-cycle crash. It’s a tragedy, as when capital is most readily available for important ideas, it is allocated most recklessly.

Compromising With Context

All of this brings us to LLMs, and the central question: are they a “better” algorithm with more context for qualitative reasoning for venture capital decisions? Or, have they simply inhereted the same biases of human investors from their training data?

There are a few pros and cons to consider.

For example, in Petit’s paper on decision making with changing resource availability, an identified challenge for investors was “laziness”. The unwillingness, particularly in hot markets, to spend time processing and analysing complex information about an investment opportunity. Here, LLMs clearly offer the benefit of streamlining this process. By making complex signals less costly, it might reduce the influence of “cheap talk” — particularly in hot markets.

Similarly, Davenport’s paper on predictably bad investments highlighted investors’ vulnerability to founders with extreme charisma. This seems like a problem LLMs should be able to avoid, unless the founder is a well-known figure and features in the training set via past writing or press coverage.

On the other hand, the problems identified in Stern and Foster’s paper, where venture capitalists built the stereotype of a “great founder”, are likely to be magnified. As these stereotypes are entrenched in the discourse of venture capital, and have influenced past investment activity, they will have been trained into LLMs. This risks exacerbating the pattern-matching problem, including amplifying negative biases like the prejudice against solo founders, minority founders, and startups outside of traditional hubs.

Biased Echoes: Generative AI Models Reinforce Investment Biases and Increase Portfolio Risks of Private Investors, by Philipp Winder, Christian Hildebrand and Jochen Hartmann, looks specifically at the manifestation of these biases in LLMs. This study found that LLMs exhibit the same cognitive biases as human investors (in some cases, more severely) and increase portfolio risk across all five dimensions measured (geographical cluster risk, sector cluster risk, trend chasing risk, active investment allocation risk, and total expense risk). Additionally, the study found that basic debiasing measures (e.g. prompting the model to ignore certain data) only partially mitigated the issue.

With all of that in mind, we can turn to two more recent papers on the use of LLMs in venture capital, how they eliminate, modify or magnify our existing cognitive biases, and the implication for their use in future.

VCBench: Benchmarking LLMs in Venture Capital set LLMs on 9,000 anonymised founder profiles to test their “picking” ability. The study demonstrated that LLMs can more confidently pick winners, beating top-performing venture capitalists. For example, DeepSeek-V3 was correct in 59.1% of its picks. However, that came at the cost of being extremely selective; it only identified 24 out of 810 available winners. In a more realistic environment (~135 winners in the sample) it would end up performing similarly to a good VC firm (picking 4 winners, 18 losers).

It’s also worth noting that a “winner” in the VCBench paper is an exit of more than $500M (or more than $500M in cumulative fundraising), which doesn’t represent an overwhelming success by today’s metrics.

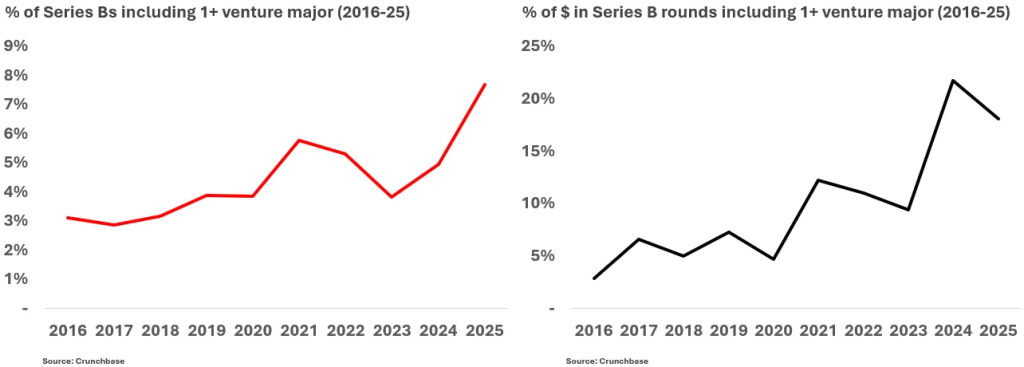

Essentially, LLMs were over-reliant on patterns and missed a lot of winners in the process. Implicitly, this approach might be more appropriate for later-stage investments in a more concentrated portfolio, or platform firms generating beta, and would struggle with the idiosyncrasy of early-stage venture capital.

Moving away from investment decisions, Generative AI-powered venture screening: Can large language models help venture capitalists? examines how quickly an LLM can analyse opportunities by distilling large sets of unstructured data. This study looks at the application of LLMs to tasks that might normally be assigned to an analyst, where it appears to be 537x faster and marginally more accurate.

While the potential gains in efficiency are immense, it’s worth considering the findings of The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers, and how long-term use of LLMs in investment decisions might impair human ability. In order to learn from past investments, investors must fully understand and appreciate why they were made. There’s a dangerous future where LLMs shape decisions, which shapes training sets, which shapes decisions. We end up stuck in a recursive loop in which venture capital loses touch with reality.

Do Things That Don’t Scale (and Scale Things That Do)

LLMs are powerful tools, but they are fundamentally backwards-looking in their reliance on training data, with limited ability to reason toward novel conclusions. Thus, they are quite specifically unsuited to early-stage venture capital investments where extreme idiosyncracy grapples with realities that may be a decade away.

That’s not to say they aren’t useful for venture capitalists. You might, for example, use an LLM to analyse deal memos and understand how your reasoning compares to real outcomes; whether your concerns are predictive of failure, or whether perceived strengths are predictive of success. A large, general model might play a part in identifying trends across research and industry which inform your thesis on future opportunities. They’re also increasingly capable of analysing financials and cap tables to produce useful insights without the typical burden of work.

In essence, LLMs can be used to wrangle data that might help shape how the firm operates. However, venture capital investments (done well) are pure alpha, extracted from the negative space. There are no patterns to work from, which precludes much of how LLMs reason. In essence, they give you a better map of what is known but they cannot tell you where to go in the unknown fog of opportunity. Indeed, this is exactly why cognitive biases also produce such a drag on venture capital investments; they are the application of patterns from the past to decisions about the future.

A Game of Telephone

Unfortunately the bias problem cannot be solved at the VC level alone. Much warped thinking spreads down through the market from LPs, who also enjoy being sold on “cheap talk” about opportunity and simple patterns. The myth of the rockstar stock picker is seductive, eliminating an awful lot of complex uncertainty from venture capital, for all parties. Far easier than embracing a reality where investors must be technically competent and disciplined.

Thus, the relationship between founder and VC, or VC and LP, is often boiled down to reductive factoids, like “venture capital is a people business”, or a “craft”. If they agree to this shared delusion that venture capital isn’t scientific, then they can abandon the hard work of scientific thought. Opportunistic founders build heat-seeking ARR printers that cater to the vision that VCs want to market to LPs. Allocation is filled, money is moved, marks go up, and most of the combined objectives are achieved.

This is the danger of LLMs. If they aren’t properly understood from a perspective of behavioral economics, they can easily be misapplied to produce even worse outcomes (both in fairness and performance) than we see today. It would be relatively trivial, for example, to create some hybrid model that performed well on VCBench, and sell LPs on how it would outperform the market in future — when no such thing is true. Instead, it would offer an accelerated version of the past, fuelling greater accumulation and faster markups, with a zero-G plummet at termination.

Affirmative Smokescreens

It’s an interesting era for venture capital, current market dynamics aside.

The optimistic case is that investors will run sensible experiments with what LLMs can add to their process, yielding a marginal uplift. The pessimistic case is that models will be thrown blindly and arrogantly at investment decisions, producing a decay which may not be obvious for years afterwards.

That fork in the road will be determined by whether or not the industry can develop a more sophisticated view on behavioral economics, and resist current incentives to embrace bias. This is part of a sustained battle to professionalise the strategy and squash rent-seeking grifters who achieved huge success in the ZIRP bull run.

Essentially, if investors are handed tools that can dramatically accelerate activity, it will end up amplifying the dominant philosophy. That could result in the more efficient allocation of capital to opportunity, or it could enable ever-greater AUM fee extraction. The worry is that incumbents already use “craft” as a smokescreen for accumulation, and LLMs offer a new and more exciting mirage of competence.

Projecting Forward

The highest performing venture capitalists in any (rational) environment are likely to have a particularly raw and tactile interface with the world. They are maximally open-minded, energetically curious, and have mastered the reflective act of developing opinions about the future. Most importantly, they have escaped the cognitive prisons of insecurity and ego — the harbingers of bias.

In the future, LLMs will empower these individuals by handling everything else. The grind of fund admin, portfolio maths, contracts, reporting and communications. Busy-work will be handled by agents, leaving the gifted to chase creativity, opportunity and serendipity. The missing heart of the AI Tin Man.

How quickly we can manifest this reality will depend on how soon we can exit the current trajectory, which itself is an artifact of broad economic financialisation.

References:

- Predictably Bad Investments: Evidence from Venture Capitalists – Diag Davenport University of Chicago, Booth School of Business, Princeton University – Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

- Machine Learning About Venture Capital Choices – Victor Lyonnet University of Michigan at Ann Arbor – Finance; Léa H. Stern University of Washington; Michael G. Foster School of Business

- Do Algorithms Make Better — and Fairer — Investments Than Angel Investors? – Torben Antretter, University of St.Gallen; Ivo Blohm, University of St.Gallen; Charlotta Sirén, University of St.Gallen; Dietmar Grichnik, University of St.Gallen

- Mirrored Matching: Facial Similarity and the Allocation of Venture Capital – Emmanuel Yimfor, Columbia University – Columbia Business School

- The Politics of Venture Capital Investment – Jeffery (Yudong) Wang, Boston College – Carroll School of Management

- And the Children Shall Lead: Gender Diversity and Performance in Venture Capital – Paul A. Gompers, Harvard School of Business; Sophie Q. Wang, Harvard School of Business

- Venture Capitalists’ Decision-Making Under Changing Resource Availability: Exploring the Use of Evaluative Selection Criteria – Noah John Pettit, University of Pennsylvania

- Daniel Kahneman Explains The Machinery of Thought

- Venture Capitalists’ Decision-Making in Hot and Cold Markets: The Effect of Signals and Cheap Talk – Simon Kleinert,School of Business and Economics, Maastricht University; Marie Hildebrand, School of Business and Economics, Maastricht University

- Biased Echoes: Generative AI Models Reinforce Investment Biases and Increase Portfolio Risks of Private Investors – Philipp Winder, University of St. Gallen; Christian Hildebrand, University of St. Gallen; Jochen Hartmann, TUM School of Management, Technical University of Munich

- VCBench: Benchmarking LLMs in Venture Capital – Rick Chen, Joseph Ternasky, Afriyie Samuel Kwesi, Ben Griffin, Aaron Ontoyin Yin, Zakari Salifu, Kelvin Amoaba, Xianling Mu, Fuat Alican, Yigit Ihlamur

- Generative AI-powered venture screening: Can large language models help venture capitalists? – Silvio Vismara, Gresa Latifi, Leonard Meinzinger, Alexander Pass

- The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers – Hao-Ping (Hank) Lee, Carnegie Mellon University; Advait Sarkar, Microsoft Research; Lev Tankelevitch, Microsoft Research; Ian Drosos, Microsoft Research; Sean Rintel, Microsoft Research; Richard Banks, Microsoft Research; Nicholas Wilson, Microsoft Research

- Startup Catering to Venture Capitalists – Xiyue (Ellen) Li, Chinese University of Hong Kong

(top image: “Ghost in the Shell”, by Production I.G)