For as long as there has been business, there has been fraud, and ‘cooking the books’ is about as old as it gets. In recent years, the extreme focus on revenue has produced dangerous incentives for founders and investors to cut corners. Those chickens are now coming home to roost.

Now a regular feature in tech media, we’ve seen a growing number of cases in which startups have been caught fabricating revenue (and associated metrics like accounts, deposits, transactions, etc). Given the focus on financial performance for venture backed businesses, it has left the impression that you might escape scrutiny if your numbers look good at a glance.

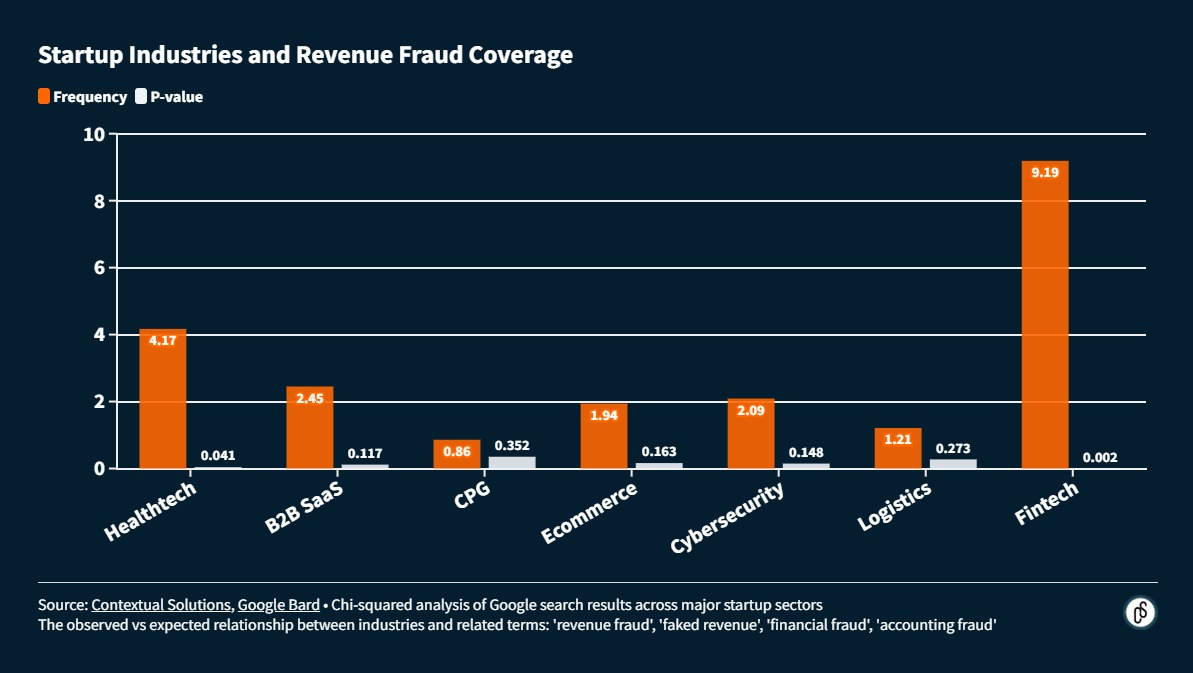

The most recent examples include Banking as a Service (BaaS) up-and-comer, Solid; financial aid startup, Frank; notorious cryptocurrency exchange, FTX; and mobile money interoperability provider, Dash. It’s not deliberate that all of these examples are Fintech companies, though it does appear that Fintech is the sector most commonly associated with revenue fraud.

Is this a consequence of the fundraising environment? Is there a deeper problem in Fintech?

The pressure of hypergrowth

While venture capital has taken a much more moderate tone towards growth in 2023, with mentions of ‘quality revenue’ and ‘sustainability’, this wasn’t always the case. Up until early 2022 the strategy du jour was raising huge amounts of capital at inflated valuations in order to fund aggressive growth to try and justify said valuations.

Companies are taking on huge burn rates to justify spending the capital they are raising in these enormous financings, putting their long-term viability in jeopardy. Late-stage investors, desperately afraid of missing out on acquiring shareholding positions in possible “unicorn” companies, have essentially abandoned their traditional risk analysis.”

Bill Gurley, GP at Benchmark

Nowhere has this been felt more keenly than in the Fintech industry, a darling of the venture capital industry since the post-financial crisis wave of evolution kicked off around 2010.

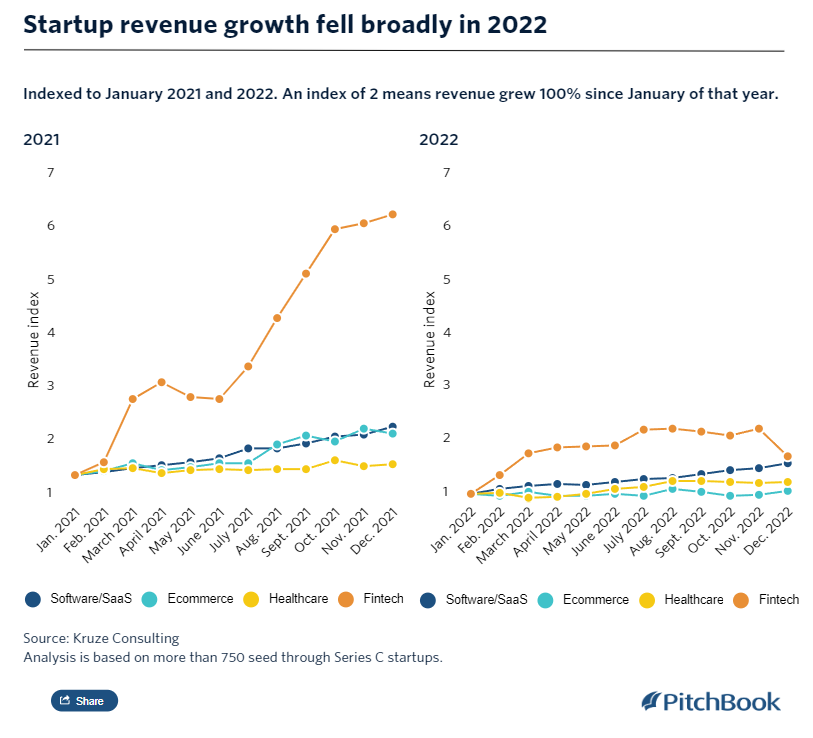

The startup-led digitalisation of financial products, including the ability to scale at a rate far surpassing incumbents by using a different playbook (see how Revolut has scaled internationally by adhering to just the regulatory minimums), has driven incredible revenue growth for Fintech in recent years.

After achieving more than 500% growth in 2021, the juggernaut Fintech growth finally began to stall in November. We can speculate on the reasons, but the chief suspects are the impact of COVID’s Omicron variant on business confidence, the beginning of the current surge in inflation, as well as growing fears of deeper economic woes spurred by the pandemic.

None of those factors will be much comfort to founders who will continue to try and live up to the expectations of the extreme growth demonstrated in 2021. For many investors, the benchmark has been set and the goal is to return to it, for the sake of their fund performance.

Smoke and mirrors

Even at the best of times you will see a range of behaviours, from subtle manipulation to outright fraud, in startup financials. With so much on the line, and relatively little accountability, there’s a clear incentive to cut corners.

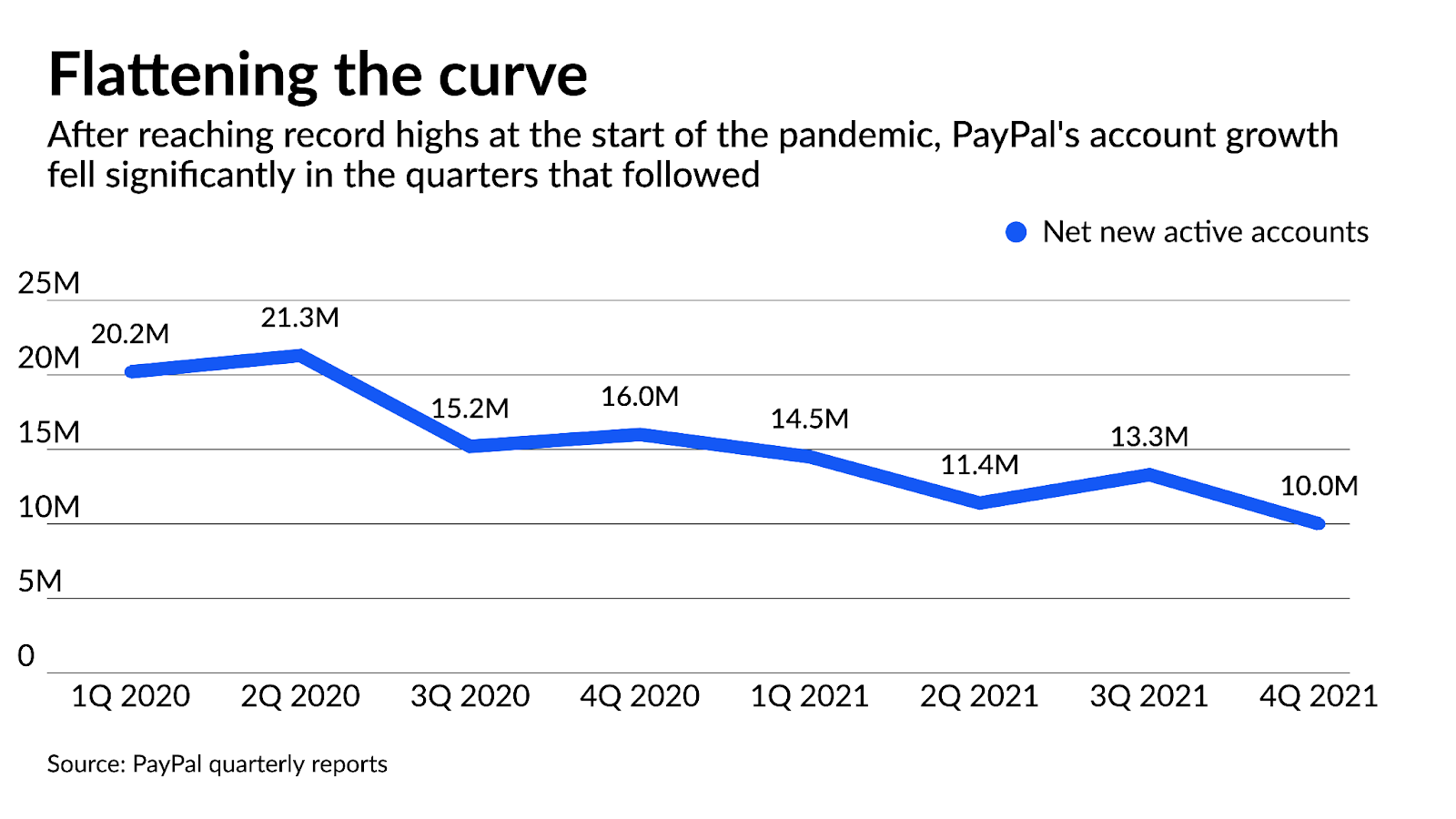

Combine that with the heights of ZIRP-drunk behaviour in 2021 and you will see real problems – even unintentional. An example of this would be PayPal’s admission that 4.5M fake accounts had been created to abuse their sign-up bonus schemes at the time. This admission was shortly followed by revised revenue projections, as they realised the huge outlay of capital was not going to yield the returns they had hoped.

Consider also how startup investments have been priced in recent years, with revenue multiples becoming the easy shorthand for valuation. In a 30x industry, as Fintech was at the peak, $1M in revenue became $30M in value – and due diligence wasn’t keeping up. Revenue was poorly scrutinized to begin with, and now it was having an outsized impact on fundraising.

The magnification of value produced a powerful incentive for founders to exaggerate revenue with any trick imaginable… of which there are many: ‘round tripping’, reporting gross revenue rather than net, sketchy definitions of ‘booked revenue’, or treating discounts and refunds as expenses rather than contra-revenue events. For many, it became common practice to fudge revenue reporting (to varying degrees) in order to inflate performance and exaggerate potential.

When I joined Flexport as co-CEO in September 2022, I found a company lacking process and financial discipline, including numerous customer-facing issues that resulted in significant lost customers and a revenue forecasting model that was consistently providing overly optimistic outputs.

Dave Clark, former co-CEO of Flexport

Unfortunately, conditions only worsened when the ZIRP-hangover began. After the leg-sweep of funding early in 2022, investors were briefly forgiving about slowed growth in the new environment but it didn’t last long. Today, founders are expected to live up to the kind of growth they had previously promised investors, without necessarily having the available venture capital dollars to afford it, all while angling more aggressively towards profit.

The crunch is real, and it will lead many founders to make bad decisions.

Challenges for investment due-diligence

A much discussed side-effect of the ZIRP-era coming to an end, with the collective tightening of belts in venture capital, is the resumed focus on proper due diligence with startup investments. This will include things like debt, leases and contracts, as well as the startup’s current and projected revenue.

This may already be catching out the lies from startups that exaggerate revenue to bump their valuation in a previous fundraising round, but it’s not always as clear cut. For this, we can look at the sordid history of GoMechanic, a startup caught in a revenue-faking scandal despite previously having sign-off on its accounts from Big Four accountants PwC and KPMG. The third time was the charm when EY finally managed to nail down where things were going wrong, including all kinds of accounting chicanery in a partially cash-based business.

This begs the question: how realistic is it for investors to catch-out revenue fraud for private companies, when there is so little in the way of enforced standards? Public companies are expected to adhere to GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Practices), but no such obligation exists for private companies. ASC 606 and IFRS 15 exist as revenue recognition standards for both private and public companies, but will continue to be ignored by startups for as long as they aren’t required by investors or properly scrutinised by board members.

For Fintech investors especially, this prompts the old debate about whether investors need to be experts in the industry in which they invest. If you are a partner at a financial services company (venture capital is really just a peculiar financing product), investing in financial services startups. should you not therefore have at least a minimum of financial literacy?

To go deeper down the rabbit-hole: there are questions about how much investors knew about some of these cases, before they were brought to light. When is it of interest to an investor to intervene, and go through the messy process of righting the ship, even when it may mean revising value downward for other investors, founders and employees? What if they just kept quiet, and let it be someone else’s problem?

Diligence isn’t cool; do it anyway

Increasingly, issues appear in the world of private company investment (and are amplified in the high risk/reward world of startups) which relate to a stark lack of transparency, accountability and regularity.

If venture capital firms invest in startups with the expectation that they will one day exit via IPO (and thus adhere to GAAP), why do they not require prospective investments and portfolio companies adhere to those standards from day one?

Startups are volatile in performance and unconventional by nature, making it impossible to standardise much about how they operate. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that conventional business wisdom is a plague on founders. However, much can be standardised about the ‘unsexy’ aspects of the fiduciary duty between founders and investors.

Founders are probably not jumping at the chance to apply accounting standards to their business. It is far easier, unless obliged otherwise, to sketch out an income statement with a degree of improvisation. A certain amount of poetic licence goes a long way for VCs, too.

However, it’s clear we are entering a new era for startups, with fresh scrutiny across the board – especially for Fintech. The world of startup investment is, slowly and painfully, moving towards greater levels of accountability.

We should also think carefully about the operating system of startup fundraising, and whether it really incentivises the best behavior and the best outcomes. I am a ‘techno-optimist’ in that I believe in the power of efficiently allocating capital to innovation… but that means real innovation, not monkey jpgs.

Leave a Reply