Web3 has largely failed, and we should talk about it

There’s an elephant in the room.

In the space of just a few months, NFT PFPs have vanished from Twitter, .eth usernames have fallen out of vogue, and a whole category of social media celebrities has vanished.

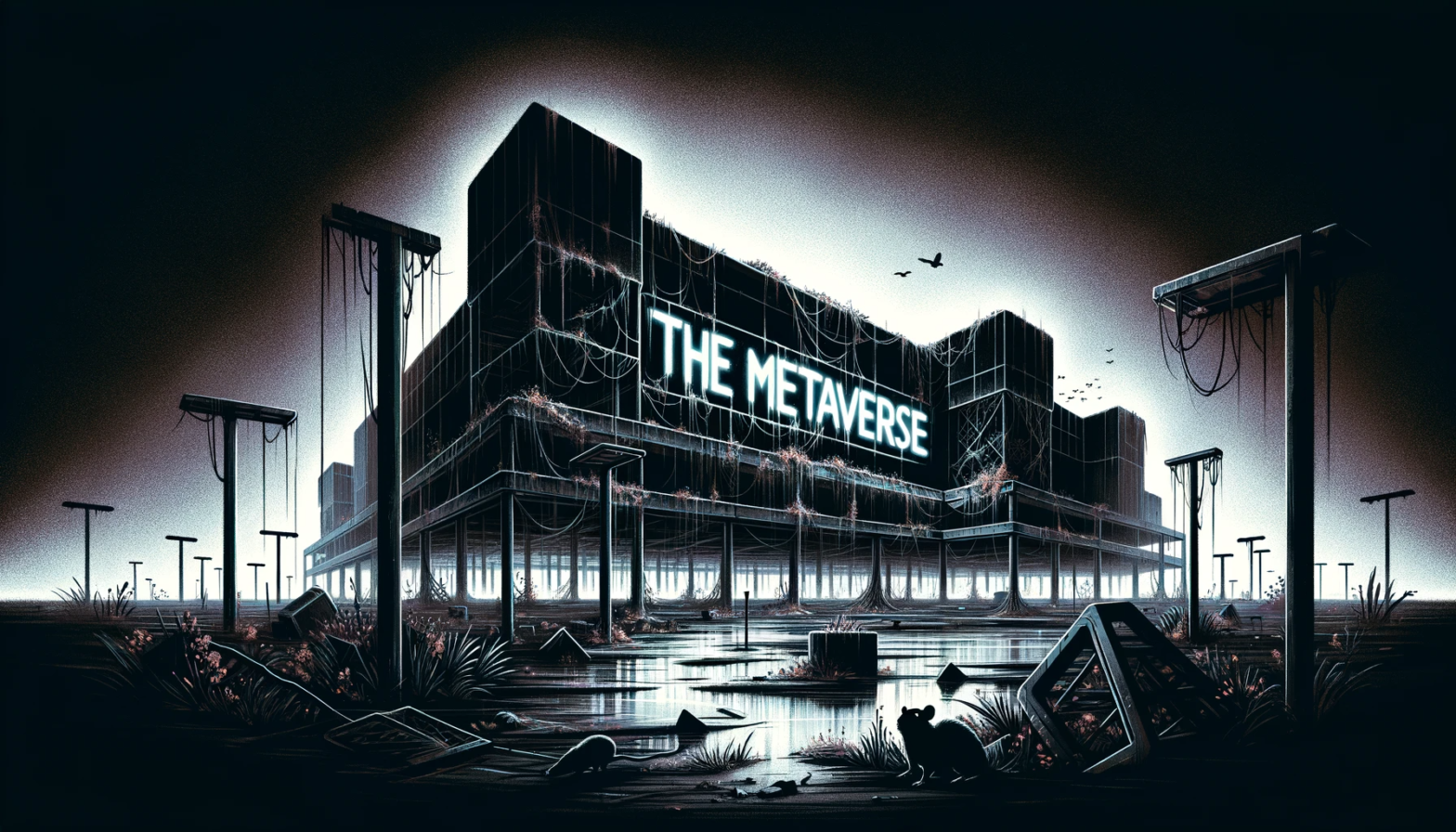

The tech world went from frothing at the mouth about the future of the internet, how life would be different in the metaverse, to “oh hey, is that AI I see over there?” and wandering off.

I’m not surprised. I’ve spent a good amount of time writing about how web3 products have ignored consumer interests, and perhaps even more writing about how web3 has had to ignore the past in order to fake progress the present.

I don’t mind that we’ve moved on. But we should talk about why. There should be some accountability and humility from those who were the most bullish.

I asked on Twitter whether anyone had dared write a web3 post-mortem:

The comparison is apt, and I suggest reading the linked article to better understand why. To summarise: the technology was cool but awkward to use, and ultimately consumers didn’t care that much.1

So what does any of this have to do with referral programs?2

The above explains fairly well, I think, why web3 failed to cross the chasm. There was technology, and there was money, but it was not being used to solve real problems. And yet, for a period of time, it had us all capitvated – if not actually invested. Why?

Web3 had a monumental referral program

One curiosity to look back upon, in all of this, is that hype for NFTs was front-running interest in ‘web3’ or ‘metaverse’.

In Feb 2021 we were keen to learn more about these magical jpgs, but it wasn’t until April that metaverse reared its head, and only by December was interest in web3 picking up steam.

But… weren’t web3 and metaverse concepts the use case for NFTs? How could the interest preceed the use case?

In the beginning, people were hoodwinked into thinking this was a ‘digital art’ revolution and – thanks to a few exceptional examples – a lucrative one at that.

‘Digital art’ seems quaint in comparison to the grand promises of an internet revolution which came later. It doesn’t matter; it was enough. Our interest was captured, and money started to flow into the ecosystem. Consider, at this point, the old gold rush analogy about selling picks and shovels.

NFTs provided a sufficient level of interest and capital for creative (and ethically questionable) people to invent new ways to sell more NFTs. Most metaverse ideas were borne out of this NFT gold rush, as well as much of what drives ‘web3’.

The more ambitious these ideas became, the more we talked about it, the more celebrities and brands got involved, the more certain it all seemed. We’d share interesting projects as ‘alpha’ in exclusive chat groups, and we’d proudly represent our NFT project of choice on social media.

The noise created was incredible, and the message was clear: join us in getting rich, or miss the train.

This fundamentally optimised web3 adoption for those who wanted to get rich, not those who were interested in building the next interation of the internet.

Trust, privacy and decentralisation? Nowhere to be seen.

Much like crypto, and for similar reasons, it became cannibalistic. People backing one project would lash out at others. All competition was a threat. There was no spirit of collaboration. All motivation was pointed toward increasing the (perceived) value of a project.

That’s a fine motivation if you are an investor, but it’s fatal when your investors are also your ‘users’. Much like a startup focusing efforts on increasing valuation rather than increasing value to users, it’s going to end with a bang.

In conclusion…

The collapse of web3 can be attributed entirely to the perversion of its growth.

The ecosystem created was built around a bubble, without any incentives for long term growth. No reason to spend time identifying and solving real problems.

It’s a shame, because buried deep in there were some people genuinely trying to build a better future, but it is incredibly difficult to maintain that focus if ‘financialization’ happens too early.

Additional reading:

Why you should rethink referral programs

About a month ago, Mobolaji Olorisade and Grillo Adebiyi, of African Fintech giant Cowrywise, released a retrospective on their experimentation with referral programs for customer acquisition.

It’s a supremely interesting read, and I reccomend checking it out, but I’ll provide a brief summary below.

In short: referral programs are a perverse sign-up incentive, which lead to all kinds of unintended consequences. Rather than calibrating your focus on your ideal customer profile, it drags you in other directions – towards those that see an opportunity to exploit the program.

Of all of the users of your product, it is the ones that found you organically, because you’re a perfect fit for their needs, which will sign up most readily and have have the greatest loyalty. In practical terms: the strongest LTV/CAC.

- If you imagine that 3D TVs had developed a similar rabidly absolutist mentality to web3 enthusiasts, demanding 3D content be exclusive to 3D TVs – and 3D TVs ONLY support 3D content, the parallels are perhaps even more vivid. [↩]

- Paid referral programs are a common growth strategy in the Fintech world, particularly in the ‘growth at all costs’ era. Startups would spend VC money on paying new users to onboard, depositing $10 or $25 in their new digital wallet, because all that mattered was rate of acquisition. [↩]