In 2014, Mark Schaefer coined the term “Content Shock“, to describe the point at which the amount of content being produced outgrew our available time to consume it. The implication being that a lot of content would be written that would be entirely overlooked.

The upshot: increased spend on SEM and social media platforms, and content that was increasingly designed to grab attention.

A similar phenomenon is happening with startups today, as highlighted by Sam Lessin, in his draft letter to LPs.

A summary of the problem:

Investors can only view so many pitches, so they rely on early signals of competence (pitch quality, MVP, early traction) to filter through opportunties efficiently. Not perfect, but it works.

Today, with AI, it’s easier for anyone to develop a high quality pitch, a slick looking MVP, and even some initial revenue. Some of these are companies that would have emerged without AI, but many are just riding the wave and trying to get lucky.

There’s a narrative violation happening right now that a lot of people aren’t talking about. The AI hype is certainly frothy and those frothy rounds are making the news. But the reality is that most AI companies just don’t get funding…

Elizabeth Yin, Co-founder of Hustle Fund

This happens in every cycle:

- Some founders see genuine opportunity to do something important with the new technology.

- Some see an opportunity to exploit investor enthusiasm to raise a load of money.

With AI, the technology driving the enthusiasm also makes it easier to build a startup. Specifically, that it makes it easier to build a startup that passes a typical VC’s filters.

The outcome is a huge amount of time spent chasing dead ends. Which may or may not involve capital deployed.

Screening for Outliers

This isn’t necessarily a problem at the first stage of screening inbound deals, where it’s relatively easy to select for a two basic truths:

- Do we think the problem is important?

- Do we think the founders are credible?

Or, in a pragmatic sense, is the startup on a path that seems likely to unlock vast amounts of economic energy?

For an example of how to scale this process, look no further than Y Combinator. For obvious reasons, that organisation has become very good at screening applications in large volume.

A central element to this process is the single slide format which partners use to review applications. It contains much of the information needed to make the judgement mentioned above, but much more importantly it doesn’t include information that may introduce bias.1

This isn’t something you should farm out to associates or agents, and neither should you rely on warm intros for signal.

You just have to do the work™.

Recognising Talent

The hard part begins when you turn your attention to a pool of viable opportunities and need to determine which have real potential.

You can make a judgement on whether you think the problem is important, which reflects on the quality of the founders in the “package deal” nature of pitches.

What you can no longer do as easily is test for founder credibility, given the glossy-finish provided by AI tools. This can be broken down in two main categories:

- Do they understand the business model?

Acquisition costs, unit economics, procurement timelines, cashflow, customer appetite, margins and moats? - Do they understand the implementation?

The physics, transaction costs, regulation, R&D, infrastructure requirements and scalability?

Previously, you could get a good understanding of this from a well-developed pitch deck and an MVP. Today, AI can fill in a lot of those answers for otherwise incompetent or poorly-motivated founders.

One clue for how this problem may be addressed lies in Sam’s letter to LPs:

A generation ago to make an investment VCs would say ‘where is your detailed business plan’. The business plan as an artifact served two purposes for investors; (1) it allowed you to ideally actually know / get up to speed on the business, (2) the form of the business plan and the thinking inside it told you something about how smart / talented / diligent the team was. It was easy for investors to process relative volume of inbound because they could read a few pages of a bad business plan (just like a bad script) and say ‘pass’ vs. ‘oh this person is smart’.

Sam Lessin, GP at Slow

Sam suggests that business plans fell out of favour because (similar to today’s problem) it became easier to build a prototype and put together a nice deck. I’d take that a step further, with some observations learned via Equidam’s 14 years in the business of valuation and fundraising:

The prolonged zero interest-rate period and the surge of SaaS solutions destroyed financial literacy in venture capital. It reduced much of the logic to a simple formula:

CAC: $20

ARR/customer: $4

Net cash: -$16

Multiple: 20x

$1 Invested = $4 in (gross) NAV For over a decade, all many VCs cared about was how soon cash-incinerating SaaS growth engines could convert capital calls into NAV inflation and enable subsequent funds.

The upshot was that investors, founders, advisors, and accelerators all forgot the basics of finance and economics. Cash flow doesn’t matter that much for SaaS… Projections are just extensions of the typical growth logic, and don’t serve a useful purpose… Theyr’e all just the same assumptions… The atrophy accelerated as capital flowed more freely, with fewer questions asked.

Another (infuriating) consequence was that in a decade of unprecidented investment in venture capital, most of the money was shovelled into recursive NAV inflation, and very little progress was made on important problems in biotech, energy, infrastructure etc.

By way of example, Equidam would have had a MUCH easier time over the last 15 years if it conjured up some bullshit private market multiples to value SaaS companies. Instead, with the mission to help get funding to the best opportunities, it has stuck by a principled and rigorous approach to valuation.

Particularly, this includes using projections properly, and consequently most of what Equidam does is actually teaching founders how to do projections well, and teaching investors how to parse them.

Fortunately, this too can be reduced down to a simple-ish formula:

- Is the founder’s pitch coherent and credible?

- If so, where do you expect the company to be, financially, in 3-5 years?

- What is the implied value at that point?

- Given typical success rates, anticipated dilution, and time to exit, what is the value today?

Essentially, the difference is that this approach looks at the specific future of the company in order to understand value, rather than applying a generic multiple to past performance. This is a much more appropriate lens when you’re looking for outliers.

The main criticism from ZIRPers is that the future is too uncertain, and projections are too unreliable. This earns them a blank stare and a strong cup of coffee.

The entire purpose of venture capital is to make well informed, rational judgements about the future. If you aren’t comfortable investing based on assumptions, then one of two things is true:

- You should not be working in venture capital.

- You don’t understand the assumptions.

(Though perhaps the second point also points to the first.)

This leads to one of the most misunderstood points about valuation, which I’ll try and use to pivot this article towards a conclusion:

Valuation is not intended to determine the right price.

It is an exercise which, when done properly, helps both sides of a transaction understand the assumptions and align their expectations. From that scenario, you get an indication of value which can inform the price you agree on, but the value is in the process itself.

Thus, the key here, and what has been missing from venture capital for more than a decade now, is a return to financial literacy, rather than financialisation.

Sit down with founders. Talk through their strategy together, using both the deck and the financial model as a guide. Connect it with questions about the business and technical implementation. Their answers, guided by your questions, should slot together to create a coherent and credible picture of the future.

Done well, this should give you a huge amount of insight into the founders, and their company.

Indeed, it turns out that founders who go through this process actually have a significantly easier time raising capital. This is one of the many reasons I’m so irate when people tell founders to “let the market price the round”. The process of valuation is so valuable, so useful, and so important to innovation.

So, you’re going to see a lot more startup pitches in your inbox over the next couple of years. It would be a grave mistake to ignore them, so you need to figure out how to embrace this process.

Step 1: Learn from Y Combinator’s process for screening deals. Particularly, learn what not to look at in order to reduce the vectors for bias in your process. Limit as much as possible.2

Step 2: Find a way to dig into this “complete package” of strategy, business model and technical implementation in a way that establishes founder credibility and can’t be faked with AI.

It doesn’t have to be all at once. You can start by asking them to send you a video talking through their financial model and deck to explain the underlying strategy and how it connects to revenue/profit targets and milestones. Eventually, though, it should probably be in-person, where hopefully you can get a sense for their passion and tenacity.

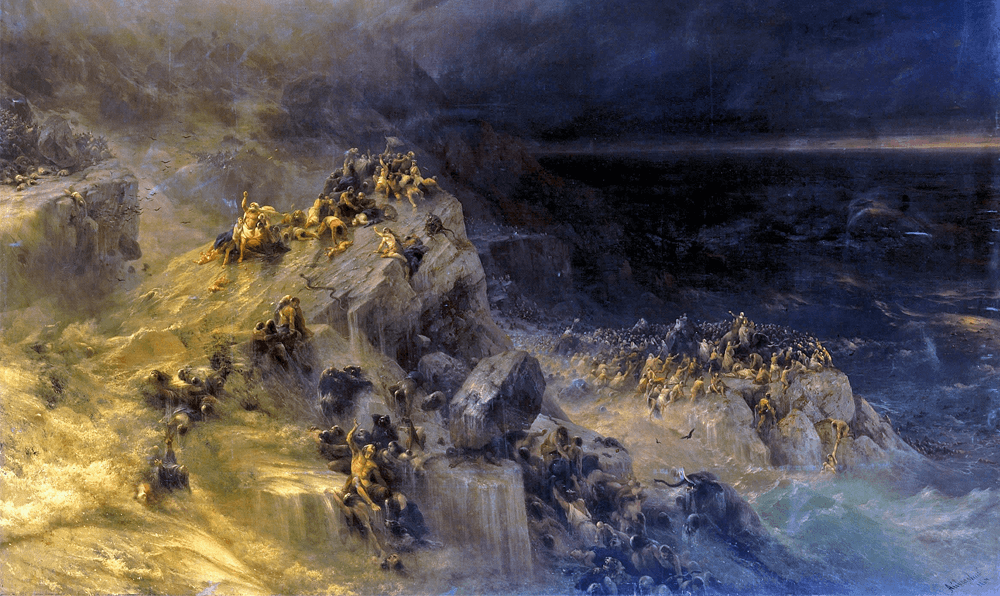

(header image: ‘Deluge’ by Ivan Aivazovsky)

- I can see why YC includes traction for their objectives, but I’d argue it’s perhaps a negative to include for a seed fund. i.e. it may bias your review towards companies with traction, rather than the best companies. [↩]

- To be honest, I don’t even like that the YC template includes the logo. It seems like unnecessary noise which may colour opinions early on. [↩]

Leave a Reply