This is a question I saw on Reddit’s often-comical /r/venturecapital, which I thought was interesting enough to write out a decent response to. It hits at the root of a few major problems in the asset class which are always worth addressing.

A 409A valuation, named after Section 409A of the United States Internal Revenue Code (IRC), refers to the process of determining the fair market value of a privately held company’s common stock. It is often conducted to comply with the tax rules governing non-qualified deferred compensation plans, such as stock options, stock appreciation rights (SARs), and other equity-based compensation arrangements.

A lovely summary from ChatGPT

First thing’s first: Generally speaking, VCs don’t care about valuation, and especially not ‘fair value’.

…and that’s quite reasonable. VCs have their own investment strategy, their own approach to calculating risk vs potential, and if it works for them (and their LPs) then great. More power to them.

What’s important here is that while we often use the word valuation in reference to deal terms and portfolio performance, what we really should say 99% of the time is price.

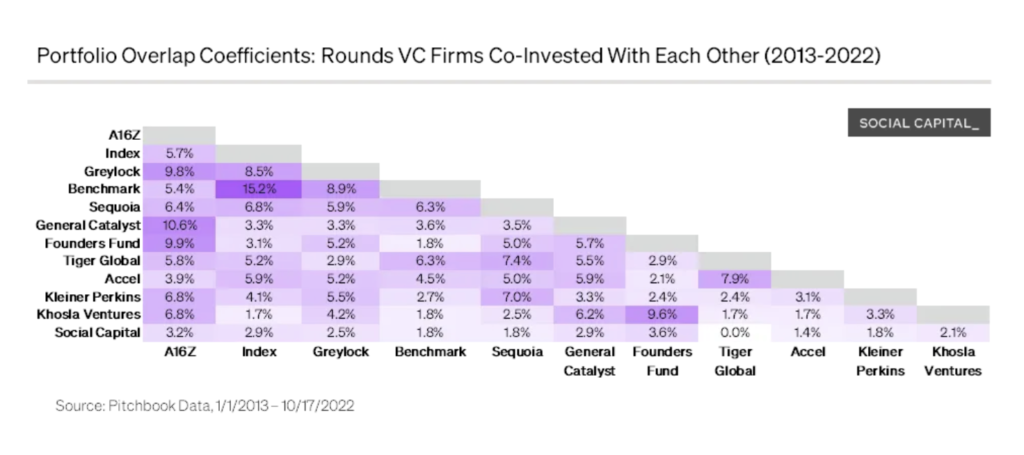

In venture capital, price factors in a number of things, including the advantages of preferred stock over common stock, but most significantly it is geared at reflecting what the market would be likely to pay for that startup at the time. This is why VCs focus so much on comparable deals when pricing rounds, even if it ends up being a bit circular, with everyone copying everyone elses homework.1

So that is the status quo. But why are VCs interested in preferred stock in the first place?

Venture capital is all about power law, right? The idea is to invest in many startups, expect to lose money on 80%, and make a varying amount of money back from the remaining 20%.

So why do they care so much about downside protection, rather than maximising that upside?

When you add a liquidation preference to a deal, the implied value of the equity increases, meaning you get a smaller % for your capital. Lower returns at exit. That kind of trade-off flies in the face of power law, so why is it of interest?

There’s a clue in this great article from William Rice:

Liquidation preferences insulate VC firms from losses, so they can delay markdowns until after they raise another fund. VC returns follow a J-curve, therefore losses come much earlier than returns. Liquidation preferences can serve as valid reasons to not mark-down investments as companies begin to miss milestones or don’t receive an exciting Series A valuation bump.

William Rice, “Slugging Percentage vs. Batting Average: How Loss Aversion Hurts Seed Investors”

Liquidation preferences are mostly an irratational response from loss-averse VCs, some of whom may be trying to shield themselves against reporting poor performance to LPs. Maybe that’s overly cynical; I’m all ears if anyone has a better explanation.

The core assertion here is that in a more rational and healthy market, liquidation preferences probably wouldn’t exist and VCs would just buy common stock.

An industry with few standards

Now that we have some understanding of how equity is priced and why preferences exist, let’s return to the original proposition: that VC investments could be marked up or down based on 409a valuations.

In some cases, VCs do set marks with 409a valuations, but not all. Unfortunately – as with much of VC – there are no real standards.2

Some VCs will only set marks based on fundraising activity, some will also consider 409a updates, some will factor new SAFE caps. Some will ignore downrounds, some won’t.

The way VCs price rounds is subjective and non-standardised, and therefore way they track the value of those investments is also subjective and non-standardised.

It might be going too far to say that this was all designed to obscure performance and protect charlatans, but this is probably how I would design VC if that was my intention.

Performance > relationships

Putting aside deal pricing for now: a VC firm could use any framework that provides a systematic read on fair value, such as this one from Equidam, and apply that to tracking portfolio company performance.

This would represent a huge shift in how VCs operate, and how they manage relationships with LPs. It’s also something that I’ve written about at some length before.

The horizon for useful feedback could be annual (or even quarterly) rather than 5-10 years.

LPs could hold fund managers accountable for performance, and we may see that many household names (which attrract the lion’s share of capital and startup attention) are actually dramatically underperforming. They could more confidently back emerging managers, who could provide more meaningful metrics of success.

VCs would be able to follow portco growth more precisely and learn much more quickly about what works and what doesn’t. Good managers would be able to fundraise much more easily.

Crucially, it would make VC an industry based on performance rather than relationships and hype chasing as it is today. It would make VC better at backing innovation, which is what the whole asset class was built around.

Startups are volatile, but capital should be stable

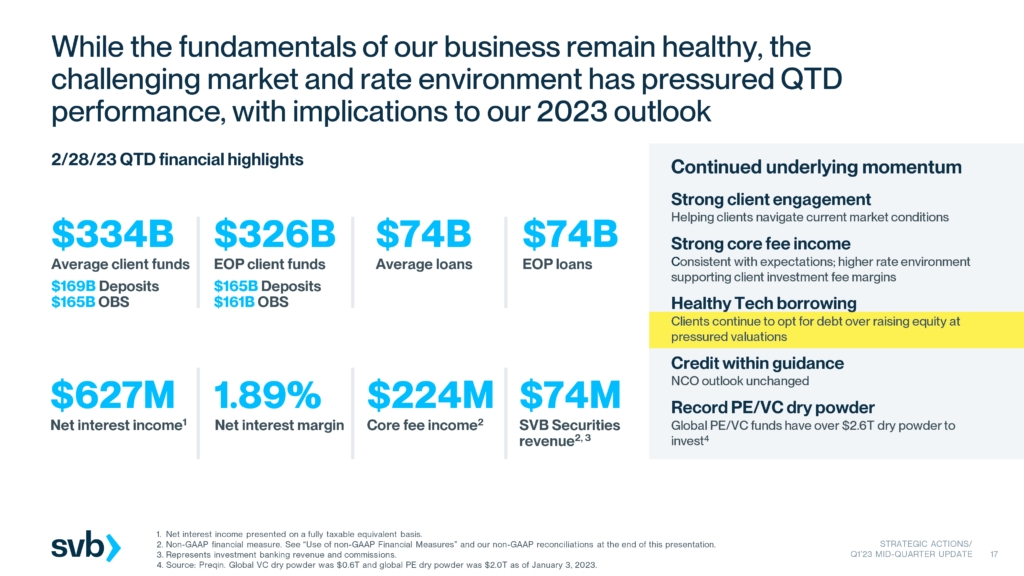

Finally, if VCs were also to price deals based at least partially on fair value, we’d avoid momentum-driven valuation rollercoasters like we’ve seen in the last two years. Much less risk of valuation bubbles and crashes, more stability for LPs and VC funds, more consistent access to capital for founders, and – again – an asset class that could better serve innovation.3

A more objective and independent perspective on startup potential, better suited to investment in the innovative outliers that venture capital was created to support.

I’ve spoken to a number of people – LPs, VCs and founders – about this topic. There’s a near universal acceptance that a standard for private company valuation would be of huge benefit to the whole venture ecosystem.

Unfortunately, none of them are particularly incentivised to make a stand on it.

Some may benefit from the status quo, and the rest are keen to maintain their relationships by not making waves.