Polish-American scientist and philosopher Alfred Korzybski is remembered for his statement, “the map is not the territory”.

The map-territory concept, which runs parallel to Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality, reminds us not to confuse the abstract with the actual. The map is not the territory. The menu is not the meal. The words are not the meaning.

Consider how this relates to the “literalisation” of the art world, from the mid-twentieth century, as described by Will Manidis:

“The collector doesn’t look at the painting and judge it. The collector reads the critic, then looks at the painting through the critic’s eyes. The painting is not an object in its own right but a theory to be validated. The taste is not in the looking. The taste is in knowing which theory is fashionable to subscribe to.”

Will Manidis, Against Taste

In this context, there is the “territory” of exploring art and how it makes you feel, or there is the “map” of critics’ opinions. The former is more rewarding, while the latter offers a lazy mirage of sophistication and intellect.

Consider how this is reflected in your own life.

When you feel like reading a book, do you explore genres you enjoy, read a page or two of likely candidates, and buy the most promising? Or, do you reach for the books which you are told are most-often read by successful intellectuals of good taste?

Then, consider the influence of signals; the Keynesian beauty contest problem, where judges are asked to pick a winner based on the number of votes they predict each contestant will get. In trying to exercise the preferences of others, their own preferences are distorted and the reality of beauty is detached from the question.

We all like to believe we have “taste”, despite outsourcing many of our decisions to others. We routinely seek the comfort of authority, rather than striving to make better judgements, despite recognising it as a crude proxy — with parallels to Daniel Kahneman’s Hazards of Confidence.

This is rational, in some situations.

If you’ve planned a movie night and have no idea what to watch, by all means look for the movie with the most postive reviews. But keep in mind…

- A well-rated movie is more likely to be good, but it’s not necessarily more likely to be great for you.

- If everyone did the same, we’d have the same small set of movies being watched, forever.

Indeed, research shows that the long-term consequence of such an environment (overreliance on social influence) would be stagnation and a growing concentration of viewership in the top-rated incumbents.

The emergence of a perverse form of “power law”.

“Hit songs, books, and movies are many times more successful than average, suggesting that ‘‘the best’’ alternatives are qualitatively different from ‘‘the rest’’; yet experts routinely fail to predict which products will succeed. We investigated this paradox experimentally, by creating an artificial ‘‘music market’’ in which 14,341 participants downloaded previously unknown songs either with or without knowledge of previous participants’ choices. Increasing the strength of social influence increased both inequality and unpredictability of success. Success was also only partly determined by quality: The best songs rarely did poorly, and the worst rarely did well, but any other result was possible.”

Experimental Study of Inequality and Unpredictability in an Artificial Cultural Market

Anchors and Followers

Ultimately, in every area of our lives, there are “anchors” who connect the map with reality (what is good), and there are “followers” who use the map as a more convenient interface (what do people think is good).

Anchors are those with the confidence to share their truly independent, personal judgement on quality. Right or wrong.

“I know what I like and what I don’t like, and I’m decisive about what I like and what I don’t like”

Rick Rubin

…and if there are too many followers, relative to anchors, you get consensus-driven stagnation; the role of anchors includes recognising the birth of new opportunities, and the death of old ones…

“The audience don’t know what they want. The audience only knows what has come before.”

Rick Rubin

Hyperreality

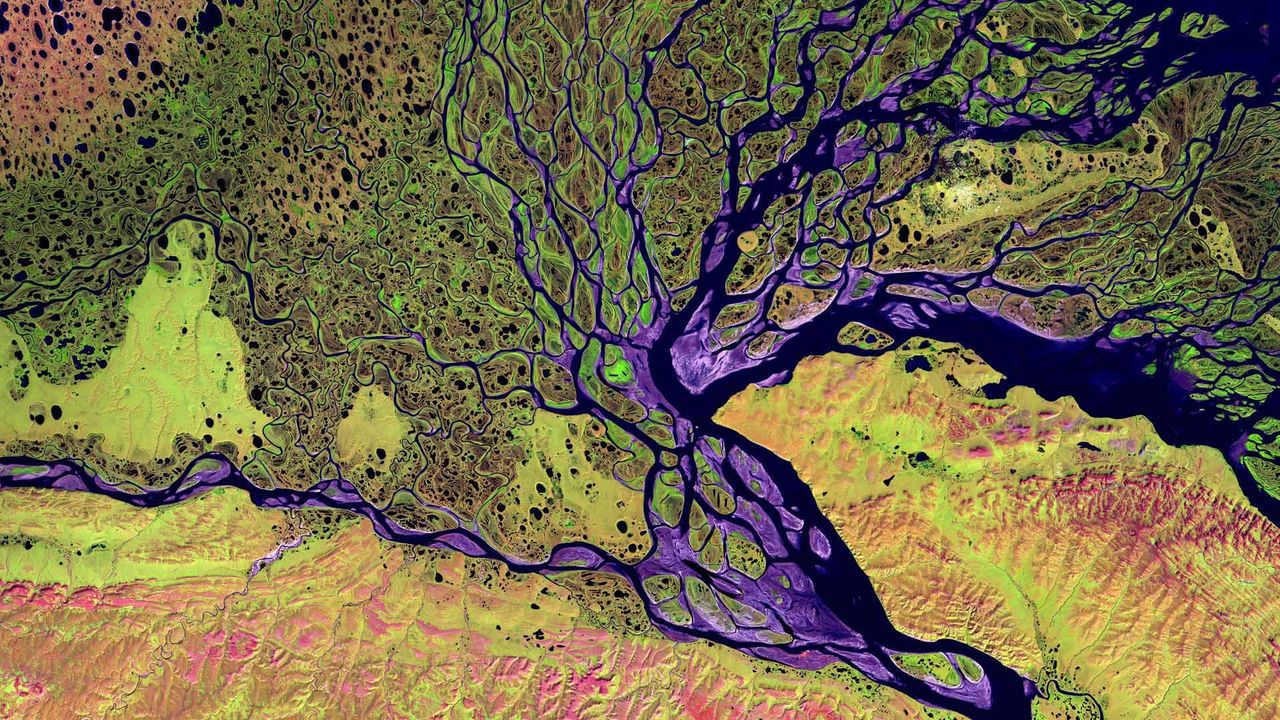

In a venture capital context, the map is a sprawling network of nodes, between which flow currents of capital and signal. These nodes may be venture capital firms, startups, angels, tech luminaries, or successful founders.

If you go back to the 70s, the map was a handful of disparate nodes with limited current. A huge amount of uncharted territory. Emerging, but inconsequential. Investment decisions were made without any regard for other investors, or even any notion that such regard would have merit. Essentially, everyone was an anchor.

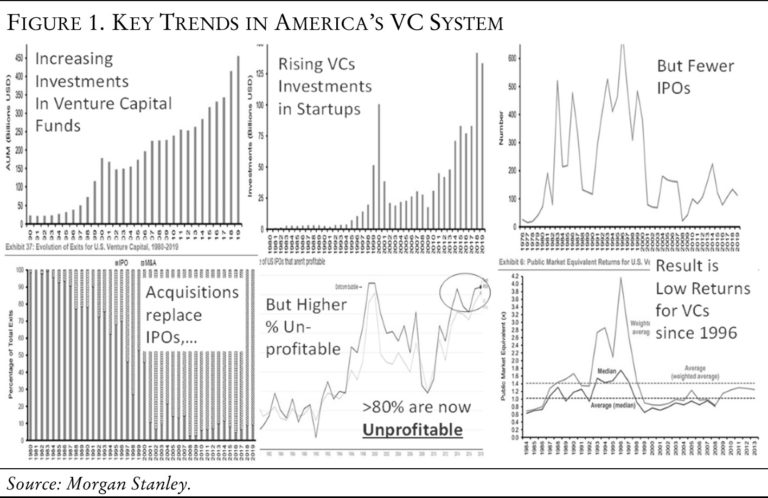

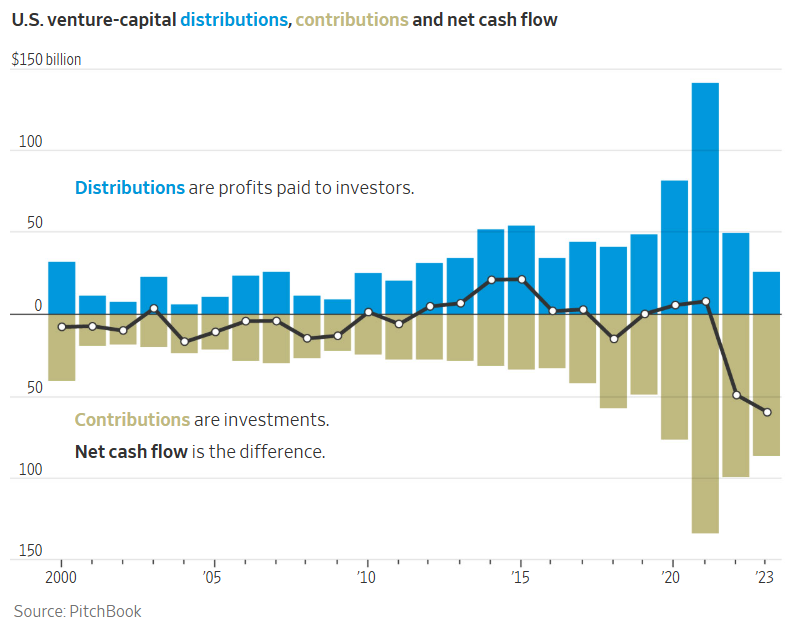

As venture capital has scaled, the map has become the primary lens of our understanding. Who’s investing in what? Which companies raised how much? What do people think about a particular technology? What is in the headlines timeline? Virtually everyone is a follower.

Signal chases capital. Capital chases signal.

Returning to the the Keynesian beauty contest, the consistent winners will not be those who best recognise beauty. It will be those who understand what a drift to consensus will do to the concept of beauty, arrive there first, and advertise it to others.

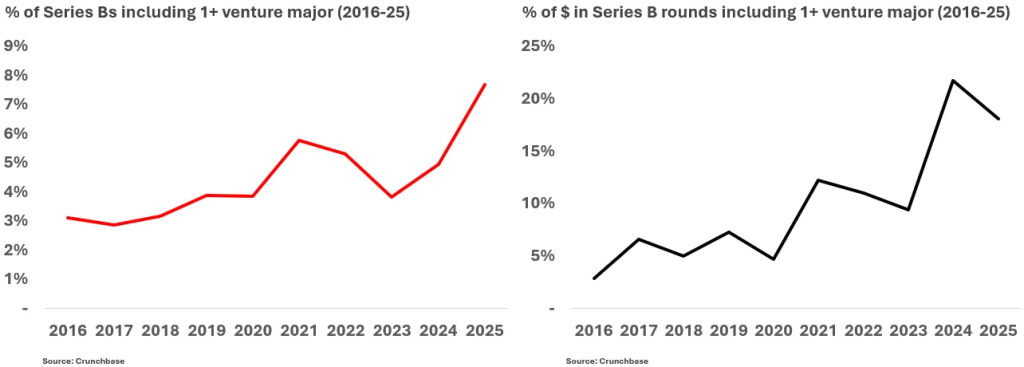

Clearly, the same forces are at work in venture capital today. The largest firms have become the fastest to understand the map, and the most able to exploit an ability to shape consensus.

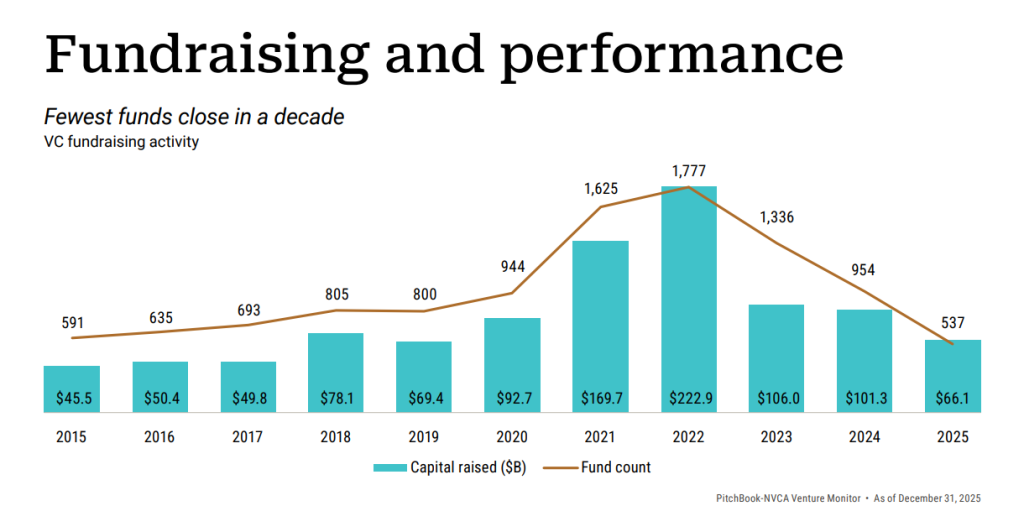

However, if everyone is focused on the map, while the actual territory is shifting, there’s a risk of dislocation — varieties of which we saw in 2000, 2007 and again in 2022.

A Brief Digression on Star Power

There are other parallels to draw between the movie industry and venture capital:

- Movie franchises and technology cycles

- Kevin Feige and Marc Andreessen

- Superstar actors and founders

A good example of the latter can be found in Michael Rosenbaum’s conversation with Jared Harris, where Harris talks about a meeting with Danny DeVito, early in his career.

DeVito praised him for disappearing into the roles he took, and wished him luck (“you’re gonna need it!”). Harris was puzzled, if he was doing a good job as an actor, why would he need luck?

DeVito explained, a good actor in hollywood is not a good actor; it’s a recognisable actor. Movie studios want stars.

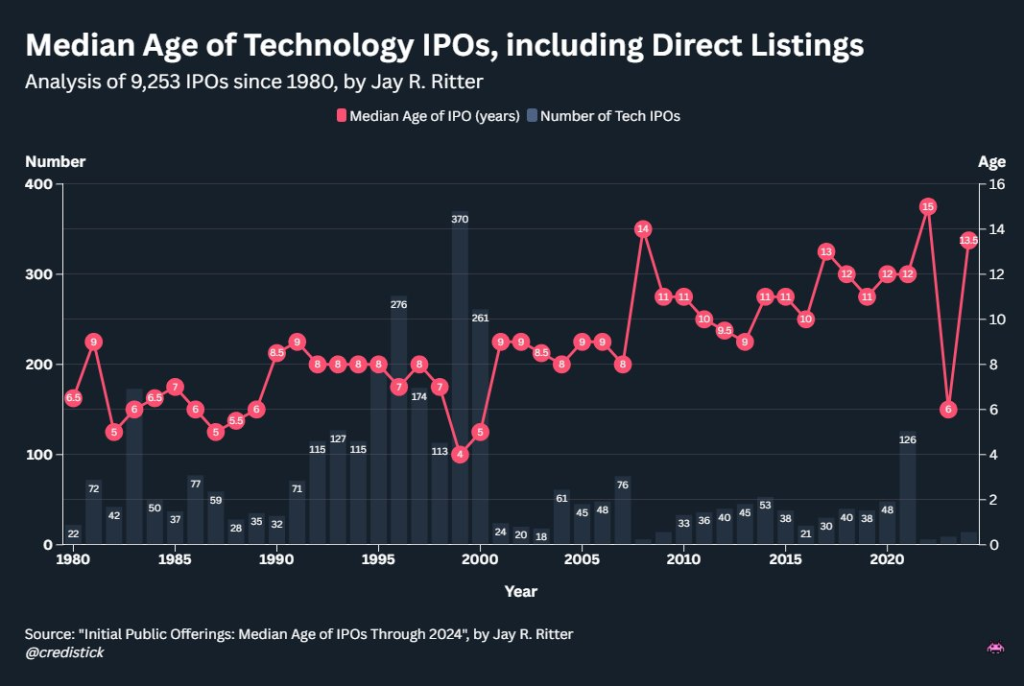

Increasingly, venture capital behaves the same way. Despite a mountain of evidence that it leads to predictably bad outcomes, venture capitalists look for the “star founder” archetype.

A good founder is not a good founder; it’s a fundable founder.

This all points back to the Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality; the point at which the map has effectively replaced the territory.

Inevitably, and recognisably, the outcome is stagnation.

Venture capital needs more anchors.

Return from Hyperreality

As elsewhere, the anchors of venture capital are individuals or organisations with trust in their process and confidence in their judgement. Examples include angels like Charlie Songhurst, firms like USV, and accelerators like Y Combinator. They have built confidence on a legacy of success.

Another crucial source of anchor behavior is from emerging managers — that is, genuine emerging managers rather than spin-outs. By the nature of their “outsider” status, and inability to compete in the consensus, they are anchored in reality.

Through their independence, imposed or otherwise, both of these groups exist in the territory of entrepreneurship, rather than the map of the venture market. Their judgment can be referenced against the map to see how far it might have drifted from reality.

Indeed, “anchors” can often be recognised by actions that contradict powerful market trends — not “follower” behavior.

For example, if you were paying attention to Mark Suster in 2021, you might have noticed him selling a meaningful percentage of his fund’s holdings. A sell signal, drowned out by the bull market, but an important anchor to reality for those paying attention.

Similarly, you might look at a firm like 1517 who have been meaningfully investing in industrial technology since 2015. A buy signal, drowned out by the frenzy for SaaS, but another important anchor to reality for those who cared.

Indeed, the extent to which the market noise (the map) drowns out these independent figures (anchors) is a primary driver of misallocation and grift today, and a reflection of the extent to which venture capital has scaled inappropriately.

Y Combinator

The world’s premiere accelerator, one of the more obvious examples above, is such a significant part of this equation that the effect has actually been studied.

“This study examined whether founder backgrounds predict funding outcomes within an elite cohort of Y Combinator startups, where all companies receive similar accelerator resources and network access. The analysis reveals that founder characteristics explain remarkably little of the variation in funding outcomes, with observable founder backgrounds accounting for less than 4% of funding differences.”

Founder Backgrounds and Startup Funding: Evidence from Y Combinator

Whatever has been “mapped” about the star quality of founders, Y Combinator rejects. It has its own process, built and refined over more than two decades. The decisions made in the screening and selection process are anchored in reality.

It’s hard to express how important this is. In a world where lazy credentialism is rampant, Y Combinator provides an alternative and more meaningful source of signal.

Consider that research shows founders will abandon ideas if fundraising is too difficult, in favour of lower quality, less innovative ideas that investors more readily understand.

Alternatively, consider research indicating that venture capital would benefit from providing better access to overlooked categories of founder, rather than simple pattern matching.

Through the strength of its signal, Y Combinator alleviates these problems — driving capital to the best opportunities; the most important ideas, and the most deserving founders.

As long as Y Combinator’s process remains scientific, objective and grounded in reality, it will continue to help drive progress.

It Takes Two

All of this is not to say that the “anchor” archetype is the only useful investor. Big pools of dumb money have their place in driving progress, but they are “followers” that need direction.

Both categories must scale together.

As the venture capital market grows, more anchor investors are needed to ensure that technology doesn’t stagnate.

Indeed, research shows that expanded inflows to venture capital have historically just increased funding to consensus opportunities, rather than opening the aperture of innovation.

“Increases in venture fund-raising which are driven by factors such as shifts in capital gains tax rates appear more likely to lead to more intense competition for transactions within an existing set of technologies than to greater diversity in the types of companies funded.”

Short-Term America Revisited? Boom and Bust in the Venture Capital Industry and the Impact on Innovation

This is why we need the boutique funds. We need more emerging managers. We need more great angel investors.

It’s why the growing concentration of capital in the hands of so few firms is concerning. It’s why the systematic enmeshment of firms and portfolio companies is worrying.

And it’s why we need programs like Y Combinator — in fact, we need more Y Combinators. I hope one silver lining of the recent political turmoil in California is that Y Combinator might decide to expand (back) to Boston. And, in doing so, proves the model can be replicated.

Y Combinator Austin? Y Combinator Miami? Yes please.

If venture capital is to scale, and to continue serve innovation properly, we need to ensure that it remains mapped to reality.

(top image: “The Geographer”, by Johannes Vermeer.)