Why the industry loves confidence men

“Venture capital has thrived in uncertainty: uncertain technologies, uncertain market trends and uncertain capital availability.”

Michael Eisenberg, Founding Partner at Aleph

Early-stage venture capital is characterised by uncertainty. Success lies in high-risk, non-consensus ideas that take many years to play out.

There are two ways that LPs grapple with this uncertainty, as institutional allocators to VC:

- Seeking competence: managers that understand how to extract value from uncertainty.

- Seeking confidence: managers that inspire the most certainty about future success.

For reasons best described by Daniel Kahneman, LPs are inclined towards the latter. This manifests as poorly managed risk; under-developed portfolio construction and overconcentration.

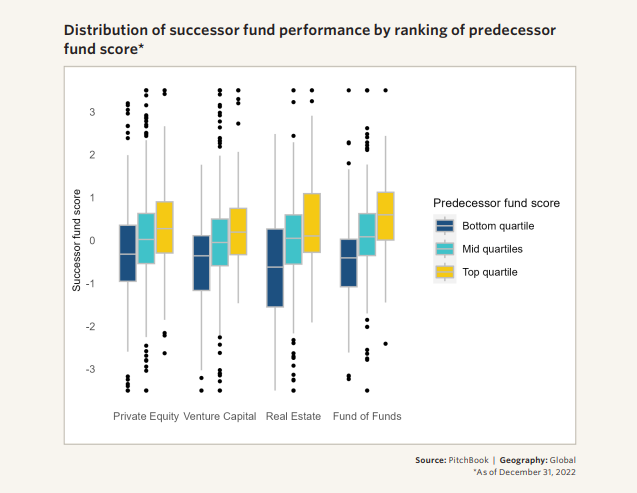

This is despite a large body of research illustrating the following:

- Overconfidence is a prevalent bias in venture capital.

- Larger portfolios are likely to outperform smaller portfolios.

- Concentration creates more downside than upside.

- Diversification encourages VCs to take more idiosyncratic risk, which drives outperformance.

Indeed, this is not without precedent. Some of the greatest early-stage VCs have unusually large portfolios: Boost VC, First Round, BoxGroup and Precursor are obvious examples.

Despite the data, and the many anecdotal success stories, LPs are notoriously hesistant to back diversified strategies. By believing they can diversify at the LP level, across a portfolio of firms, they miss the systematic benefits of diversification and inhibit the compounding gains from process refinement.

Portfolio Maths

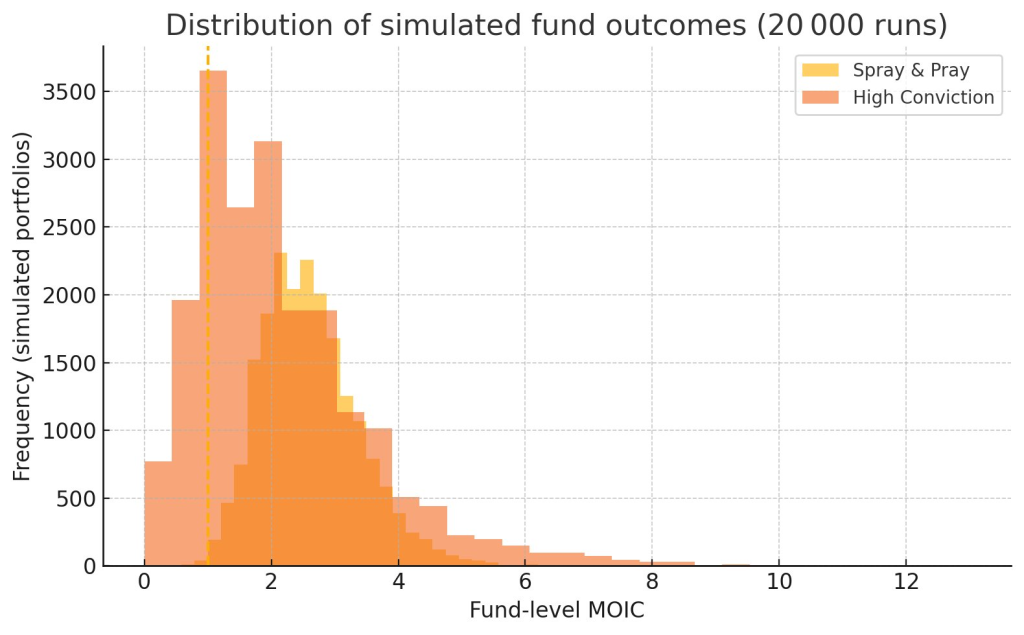

Earlier this year I posted a breakdown of expected venture capital returns based on simulating two seed portfolio models: one with 100 small checks, the other with 20 larger checks.

The graphic was meant to illustrate a simple point: based on a typical range of VC outcomes, the more diversified portfolio was likely to outperform, delivering a narrower and more attractive band of potential return scenarios.

“Typical” is the operative word there, as while the graphic implies the diversified portfolio wont exceed a 6x return, that’s only if you deliver average performance. It’s entirely possible for a GP to outperform in either strategy — although research indicates that the diversified portfolio is likely to have more upside.

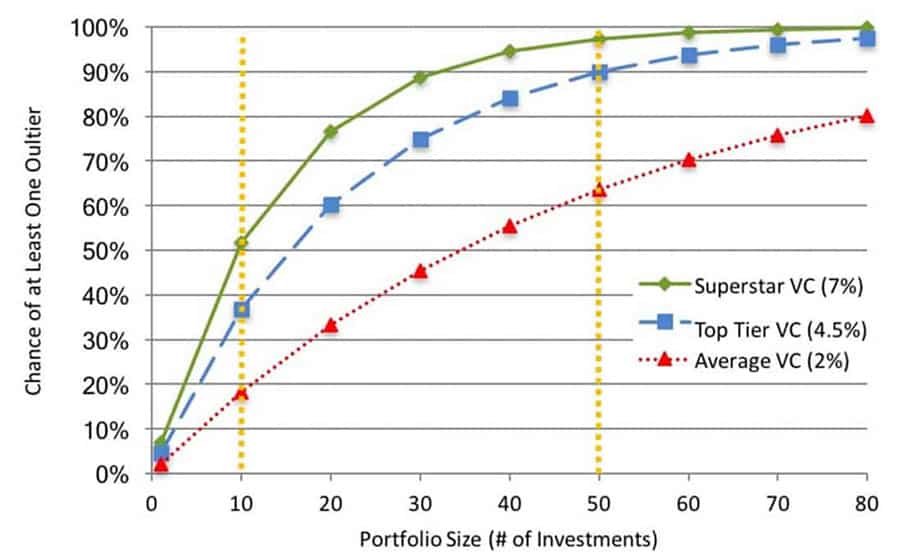

The statistical basis for this is simple: given venture capital’s reliance on outliers outcomes, the low probability and low predictability of those outcomes, it is more beneficial to make more investments (with lower ownership), than to have more ownership (with fewer investments).

There are similar simulations and portfolio calculations from a number of other sources, which all point to the same conclusion: venture capital is systematically and unnecessarily overconcentrated.

The coversation that followed (credit to the always-insightful Peter Walker for sharing it with his audience) highlighted a deeper problem with the industry’s understanding of portfolio strategy, risk management and cognitive biases.

Overconfidence

A good place to start is Daniel Kahneman’s work on cognitive biases in investing:

“The confidence we experience as we make a judgment is not a reasoned evaluation of the probability that it is right. Confidence is a feeling, one determined mostly by the coherence of the story and by the ease with which it comes to mind, even when the evidence for the story is sparse and unreliable. The bias toward coherence favors overconfidence. An individual who expresses high confidence probably has a good story, which may or may not be true.”

Daniel Kahneman, “Don’t Blink! Hazards of Confidence”

As a crude summary, imagine an LP speaks to two VCs:

- One says they’ll invest in 100 companies and expect that ~75 of them will be be writen-off. The fund returns will primarily hinge on ~1-5 investments.

- The second explains that they have a powerful network advantage, and they’ll deliver huge returns from concentrated ownership in just 15 companies.

The LP is likely to go with the second VC, who builds more confidence by telling a simpler and more coherent story; they simply have access to “better investments”. What’s not to love?

And few investors demand diversified funds, so GPs don’t offer them. A slow and steady “venture is a numbers game” pitch is much less emotionally compelling than “I am a rock star who can consistently beat the odds.” And GPs need an emotionally appealing pitch to get funded.

The Pervasive, Head-Scratching, Risk-Exploding Problem With Venture Capital

LPs want to hear confidence, so that’s what VCs offer. Thus, “overconfidence” is by far the most prevalent and dangerous cognitive bias in VC behaviour.

This mode of favouring confidence over competence leads to a number of dogmatic beliefs amongst the LP community:

- That relationships drive better investments in VC — which is only vaguely true in hot markets when it’s easy to collect markups from your friends.

- That venture capital funds themselves operate with power law outcomes — which is only true because of the unnecessary and toxic levels of concentration.

- That VCs are supposed to “pick” their way to success — rather than relying on well designed origination strategies and a systematic approach to capturing outliers.

Overconcentration

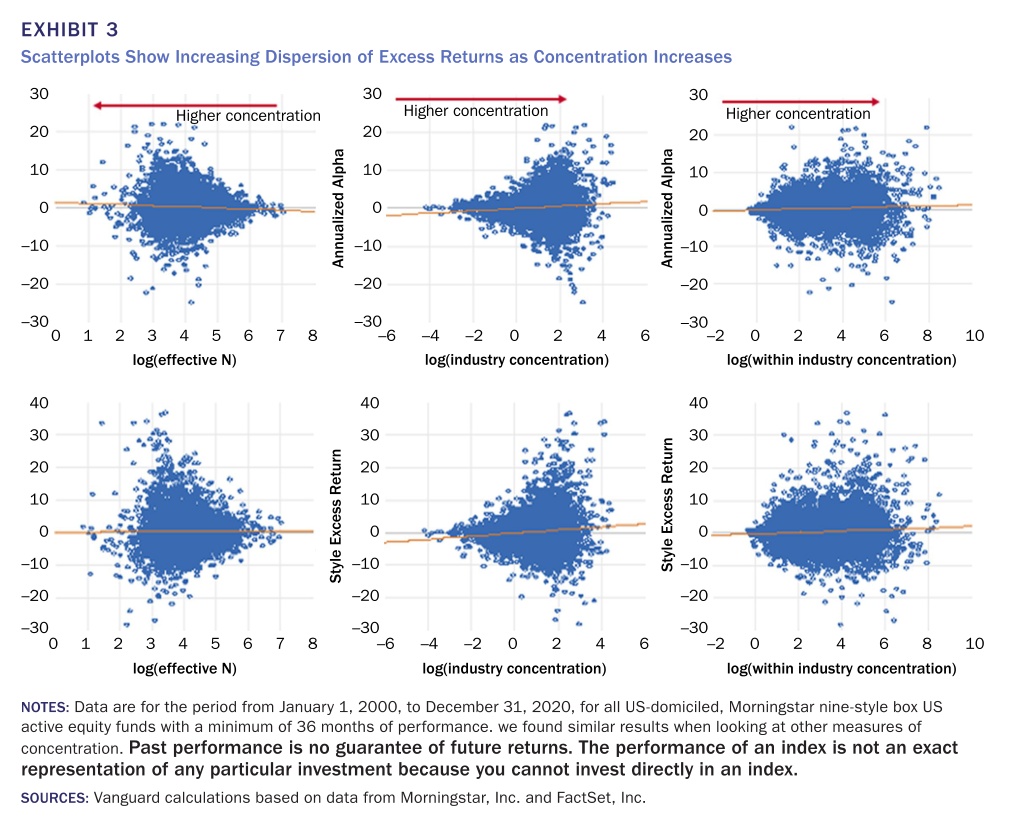

Overconfidence primarily manifests as overconcentration; portfolios with poorly managed risk. Too much capital, concentrated into too few investments, with high levels of uncertainty. This is typically measured with the Sharpe Ratio in grown-up investment strategies.

The influence of concentration is obviously double-edged, as it compounds both good and bad investment decisions.

However, research shows that this amplification is not evenly distributed: overconcentration hurts underperformers more than it helps overperformers.

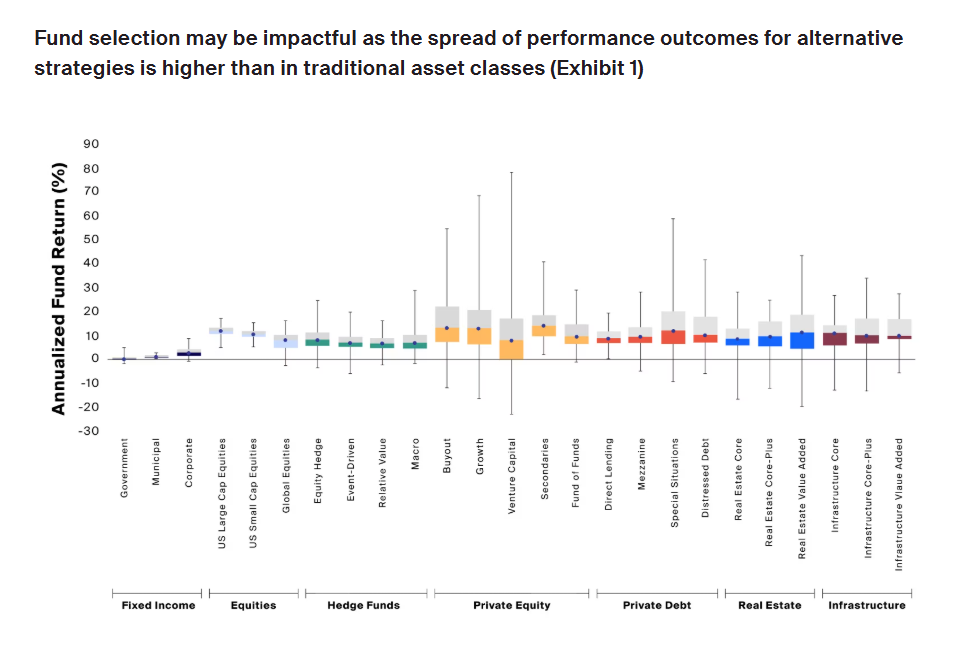

So, if venture capital were systamatically overconcentrated, you would expect to see a wider distribution of returns and a lower average return, relative to other strategies. As it happens, that’s an accurate description:

Persistence

There’s a good argument that the poor persistence of performance in venture capital can be attributed to shallow narratives around “picking” which undermine basic theory around portfolio construction and behavioral economics.

Not only does this damage persistence, it’s particularly toxic for new entrants who may attempt to piece together a strategy from the “common wisdom” available to them.

Instead of being encouraged to adopt practices that are optimal for more consistent above-benchmark returns, emerging managers are pushed toward the “rockstar” narrative of outsized promises.

Thus, they end up taking excessive risk and, more often than not, imploding; only 1/3 managers make it to fund 2, and only 1/10 make it to fund 4 .

You might raise an eyebrow at this, if you are familiar with the history of venture capital incumbents strategically freezing out new entrants in order to maintain advantageous pricing power.

Intitutional Insecurity

“Perhaps the most powerful lesson from Marks is the idea of ‘uncomfortably idiosyncratic’ investing. Citing the late David Swensen of Yale, Marks emphasizes that successful investment management requires taking positions that feel uneasy because they go against the grain.”

Howard Marks on ‘Behind the Memo’:

If investment performance is driven by adopting “uncomfortably idiosyncratic” positions, it’s reasonable to assume this is especially true for early stage venture capital — where non-consensus investing drives outperformance.

“You will know you are doing real venture capital when you aren’t competing with other investors to finance a deal but are instead offering to invest in people, industries and ideas that don’t yet have access to capital. That is where money can be most useful, and also where returns can be the highest.”

Sam Lessin, GP at Slow

VCs take a systematic approach to managing idiosyncratic risk through portfolio construction; optimising for larger outcomes and failure rates than other strategies. Indeed, VCs with larger portfolios appear comfortable accomodating more idiosyncratic risk, which ultimately contributes to stronger performance.

In fact, you could probably summarise the VC strategy as the art and science of systematically extracting value from idiosyncracy.

The lingering question, given all of this evidence, is why aren’t larger early-stage portfolios the default in venture capital?

The answer is agglomerator-leak; the “loudest model” of the mega-funds, which ends up influencing practices and perceptions across the whole venture market.

For example:

When you are investing billions in each cycle, you must pry your way into hottest companies of each vintage. The future of your firm depends on those bloated private-market darlings, and there is significant career-risk associated with missing them.

Thus, a number of ideological artefacts are spawned:

- “You must be in the category winners, at any cost.”

- “Only a handful of outcomes drive returns for each vintage.”

- “Concentrated ownership drives outperformance.”

These artefacts latch onto insecurity like Pinterest self-help quotes. GPs and LPs looking for confidence through coherence, biased toward simple ideas, lap up this accessible wisdom from venture’s most influential characters.

Unfortunately, it means they apply the same thinking to early-stage investing, and much smaller funds operating a very different strategy, even when all evidence suggests that’s a very silly thing to do.

Process Alpha

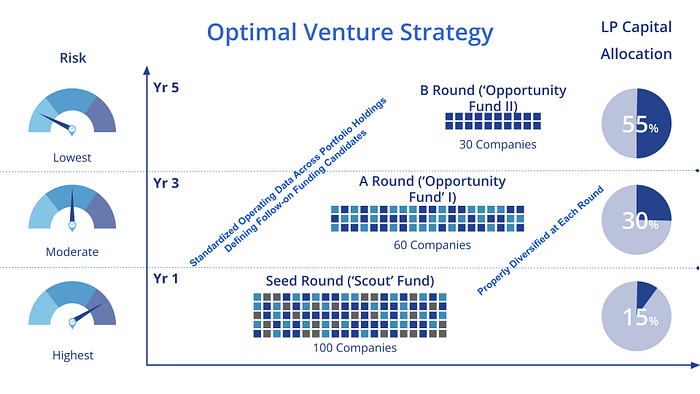

From a well-diversified base of initial investments, it is possibe for a VC to double-down on winners over subsequent rounds. This is a process that Joe Milam, founder of AngelSpan, has dubbed “process alpha“.

Staging your capital deployment properly over multiple rounds dramatically improves the IRR for investors, regardless of the MOIC/DPI. And given the natural failure rates of startups (usually within the first 2 or 3 yrs), optimizing on how much you invest in each round improves the risk-adjusted returns available.

The Impact Of Proper Venture Portfolio Construction-Optimized DPI & IRR

Essentially, this is how a VC can take the solid foundation of a well diversified initial portfolio and then build on that position with staged deployment into the best opportunities that emerge in subsequent rounds.

Conclusion

While it’s difficult to get into specific recommendations, it seems safe to make the case that early-stage venture capital firms should probably be significantly more diversified.

More importantly, the LP:GP interface is clearly problematic, and LPs need to think carefully about whether they bias towards confidence over competence.

In order to do so, they must grapple with the economic theory, and the reality of portfolio construction, to recognise why it’s important that there be a good level of diversification at the VC portfolio level.

“You should not take assertive and confident people at their own evaluation unless you have independent reason to believe that they know what they are talking about. Unfortunately, this advice is difficult to follow: overconfident professionals sincerely believe they have expertise, act as experts and look like experts. You will have to struggle to remind yourself that they may be in the grip of an illusion.”

Daniel Kahneman, “Don’t Blink! Hazards of Confidence”

(top image: The Cardsharps, by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio)

Leave a Reply