The state’s role in creating positive-sum games

Many countries have developed policy aimed at supporting the growth of domestic venture capital ecosystems — hoping to close the gap with the US.

In the EU, a key premise is that that underdeveloped private markets leave a “‘growth-capital gap” for scaling companies, limiting the potential of EU-based tech startups.

This problem is one of the key targets in Mario Draghi’s report on EU competitiveness.

Bluntly, this is what happens when bureaucrats are left to design industrial policy: Solutions are designed to patch-over outcomes, ignoring a more problematic diagnosis.

In truth:

- There is less growth investment in the EU because there are simply fewer attractive investments.

- The most obvious opportunities are snapped up by faster-moving US investors with stronger brands.

- Thus, there is even less market impetus for the development of the EU’s growth capital environment.

So, pouring money into this “growth-capital gap” has predictably negative outcomes:

- It disproportionately funds low-performing companies who cannot raise from independent investors.

- It enables an extractive layer of service providers, consultants and corporations who exploit inefficiency.

Instead of addressing a lack of investment by injecting more capital, the EU must tackle the root cause: aiming policy at generating more opportunity.

Instead of allocating capital to a known quantity of growth-stage companies, policy must drive capital into raw potential, at the earliest stages, with faith that it will electrify entrepreneurship.

The “inception capital gap”

To frame this with a few obvious but important facts:

- The EU has a significantly larger population than the US (450M vs 340M).

- Pre-seed funding in the US was approximately 13x the scale of pre-seed funding in the EU in 2023.1

- Angel funding in the US was approximately 23x the scale of angel funding in the EU in 2023.2

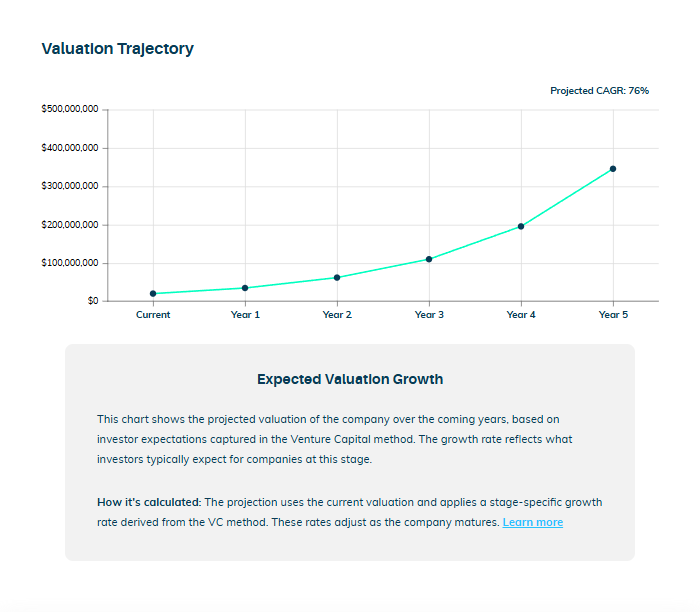

While the growth-scale capital gap might appear more obvious in sheer scale (the total US VC environment is ~$130B larger than the EU / about 4x the scale), it is important to remember that all growth activity is downstream of early investment.

If companies cannot raise angel capital, or institutional pre-seed and seed rounds, they will never reach the point of contributing to the opportunity of growth-stage investment.

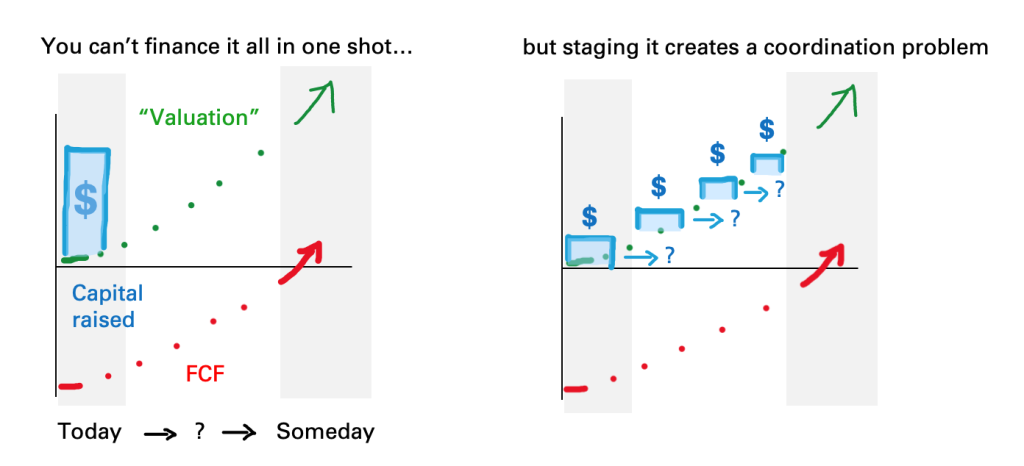

Breaking Zero-Sum Loops

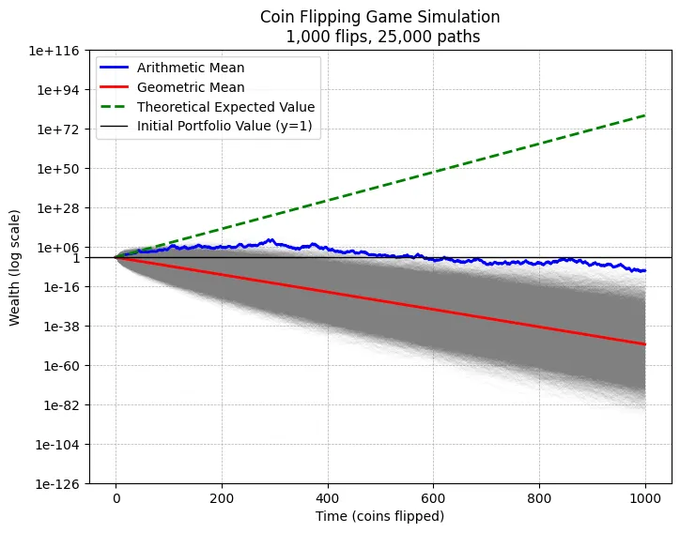

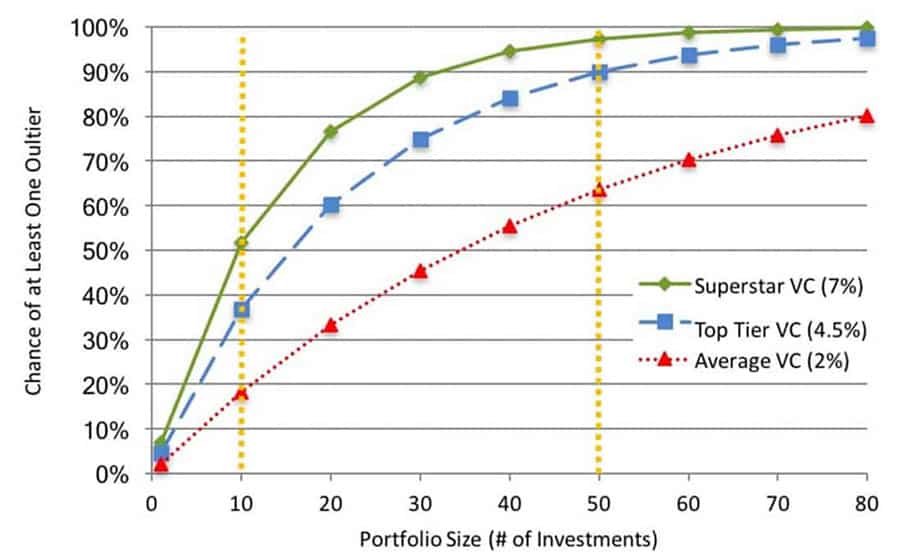

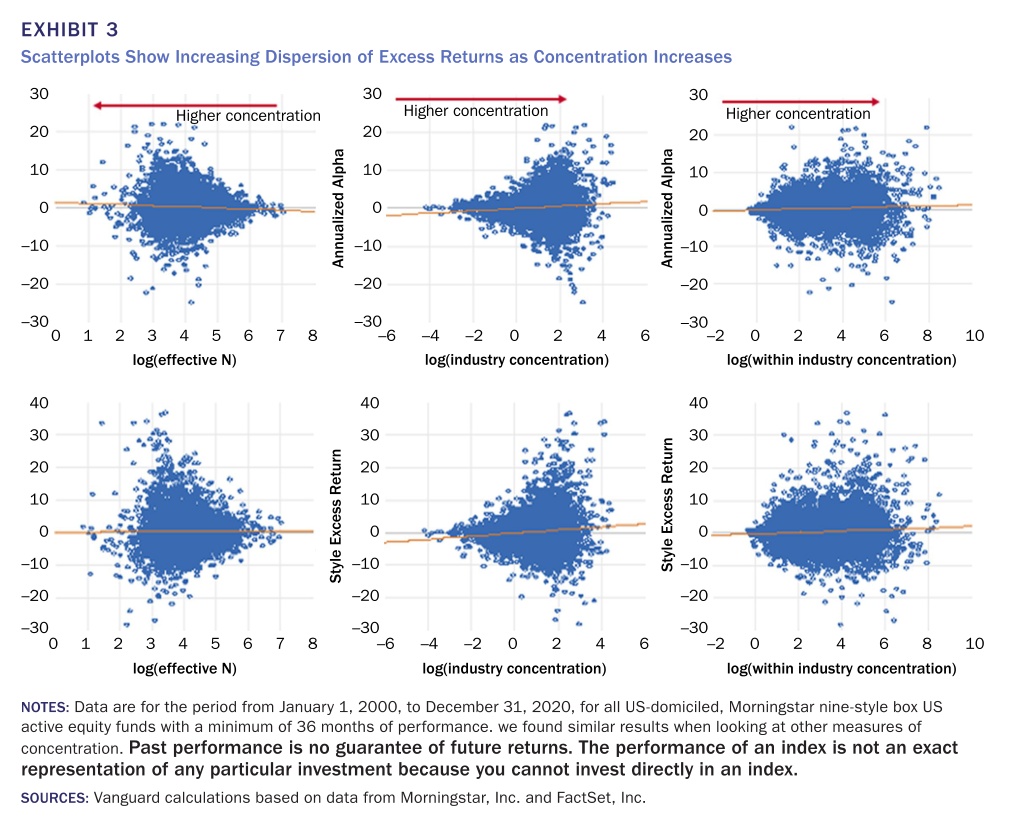

The problem many young venture capital ecosystems face is that haven’t truly embraced the spirit of (ad)venture: escape from zero-sum thinking.

The usual loop looks something like this:

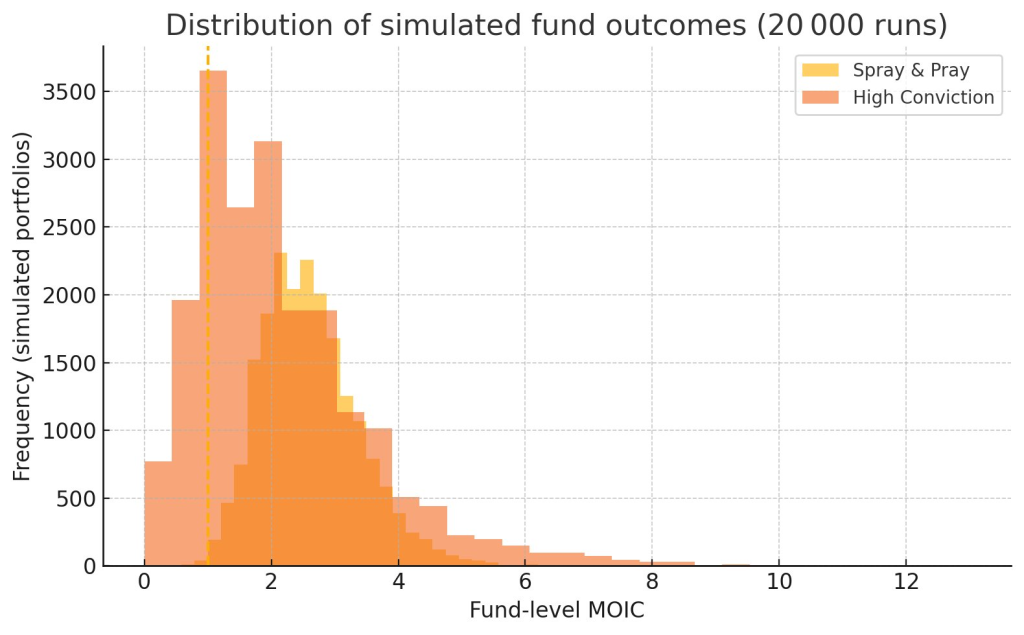

- A small pool of early-stage capital has a lower risk-appetite which manifests as restrictions on access.

- Restricted access means safer investments in companies that are inherently less likely to be outliers.

- It’s also reflected in credentialism and pattern-matching, which further erode returns over time.

- The outcome is a limited number of great outcomes which cannot sustain significant growth of the ecosytem.

The US was able to break this loop via a cultural tolerance of risk. Particularly, a general trend toward positive sum thinking and looseness, often described as a “frontier mentality”.

Outside of the US, this may be harder to achieve. Leverage can be applied via policy to help break the catch-22: finding motive to invest in the potential of future investment opportunities.

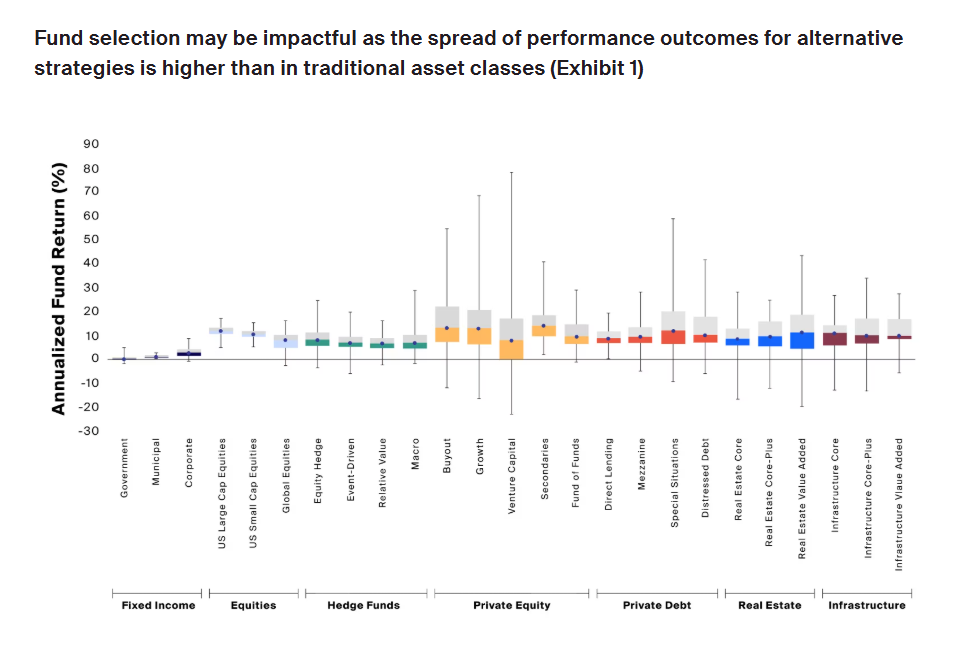

This is particularly true for institutional LPs, who are unfamiliar with the idiosyncracies of venture capital and more likely to think in Private Equity terms — reluctant to back GPs at the earliest stages, who take the greatest risk.

Manifesting opportunity

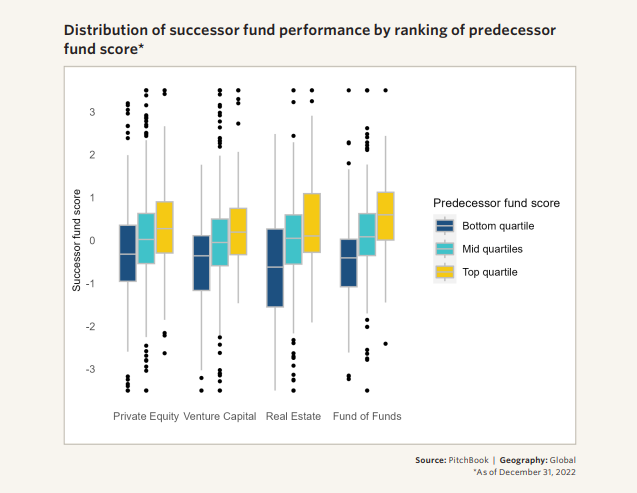

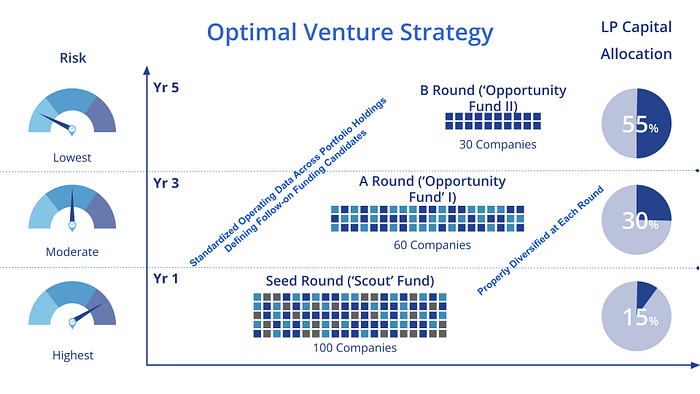

Following this logic, the role of the government should be to fund emerging managers (funds 1-3) who target venture capital investment at the earliest stages.

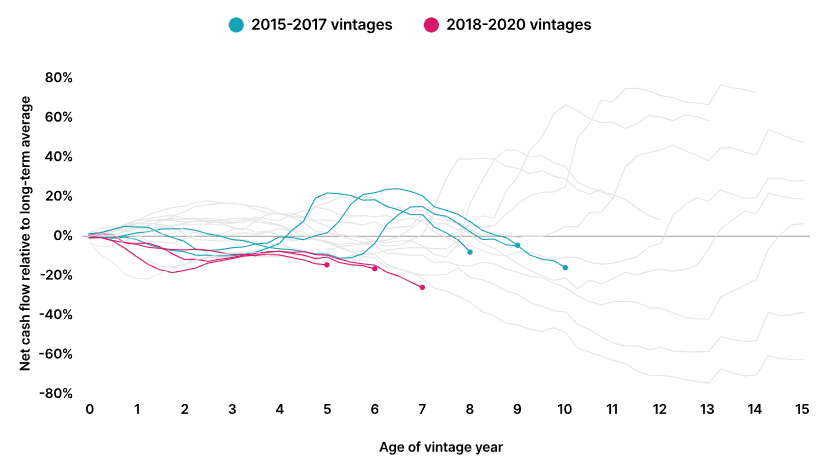

This allocation would be reduced over time as emerging managers develop their track record and attract more private LP capital. By fund 4, with roughly a decade in the market, GPs should be able to function independent of government capital.

By increasing the capital availability for early-stage managers, they will increase risk appetite, diversify what gets investment, and enable a range of more innovative origination strategies. Esssesntially, this promotes the “entropic distribution” of capital, where capital flows through the cracks and crevices of industry to seek opportunity.

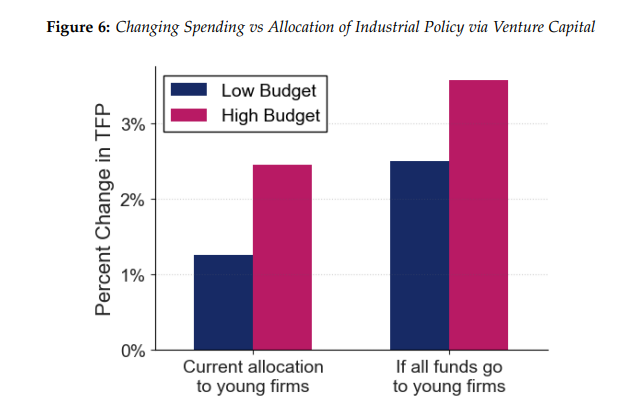

There is already significant data out there to establish that this approach works:

- Shifting allocated capital to early-stage investments produces the same uplift in productivity as doubling the total capital allocation (according to a 2025 study of government venture capital investment in Europe).

- Where governments fund emerging managers, they can produce above-market success rates (according to a 2024 study of activity in 15 EU member states) and better rates of job creation (according to a 2018 study on government-backed VC firms in Europe).

In addition, the lack of angel activity should be addressed more directly via tax reduction schemes — especially for employee stock compensation. Stock compensation is how Europe can create a flywheel which distributes success into new opportunities.

Summary: lessons for the EU (and beyond)

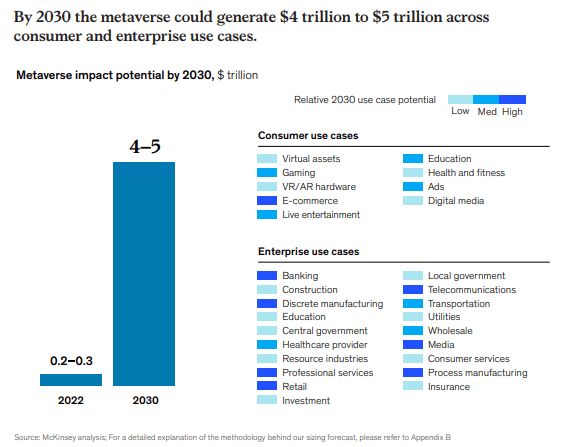

There is a significant delta between US growth-stage investing and EU growth-stage investing, and a lack of EU scale-up success stories.

At a glance, the obvious policy move is to push capital into growth investing. Indeed, the EU already commits significant capital to private markets — e.g. 37% of 2023’s VC total.

This is the EU throwing huge sums of money at symptom management. A colossal waste.

The more pressing concern (which could be addressed at less expense) is the gaping chasm between US angel and pre-seed funding versus the EU. Funding the generation engine of entrepreneurial potential.

Indeed, the EU is stuck in zero-sum thinking which is reflected in attitudes across the bloc; in competition between hubs, between governments, and even between specific actors within those ecosystems.

If institutional LPs in the EU are hesitant to solve this problem, by committing to the uncertainty of emerging managers in the earliest stages, the state should consider stepping in.3

While this is an almost non-existent view in policy today, the data is clear that this is the central opportunity for government investment in venture capital across a number of metrics:

- The growth of startup ecosystems

- Enabling technological innovation

- Driving high-skill job creation

- Return on government investment

- Feeding downstream growth ecosystems

(top image: The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder)

- A rough approximation of Europe minus the UK, and US data from Carta [↩]

- Calculated using EBAN per-country data, report also includes US estimate. [↩]

- Potentially with asymmetric terms that offer leverage to participating private institutions. [↩]