Early-stage VC can be one of two things:

- A complex, collaborative and positive-sum discipline

- A simple, adversarial and zero-sum competition

The difference between the two is whether or not you pretend there’s a legitimate consensus on “good deals”, and therefore whether competition and access are meaningful forces.

If you embrace this fantasy, a few convenient things happen:

- You can win at VC by brand building

- You can win at VC by exploiting relationships

- Venture capital becomes “scalable”

- Capital and influence concentrates

Thus, venture capital morphs from a loose collection of boutique investors into an oligopolistic mob.

The rent-seeking behavior this enables is so seductive that it has been able to resist all contrary evidence:

- Venture capital exhibits weak persistence of performance

- Relationships do not contribute to persistence

- Consensus investments underperform

- Scale erodes returns

What’s left is an industry with few leaders and many followers. For the weak-willed majority, conviction atrophies and cements their position as vulnerable minor parties in a commensal relationship.

While this is problematic in a few obvious ways (the failure of fiduciary duty to LPs, the failure to founders), there is one critical issue: it completely undermines the positive-sum attitude that has been central to venture capital’s success.

Finite Games and Infinite Games

You might hear investors saying that venture capital feels more competitive than ever. What they really mean is that venture capital is more adversarial than ever.

As power and capital concentrates, and the focus is increasingly on winning a finite number of the “best” deals in each vintage, venture capital is necessarily less competitive.

Truly competitive games are infinite games. You don’t just care about winning, you also care about the scale of that win.

To use basketball as an analogy:

A finite game player might simply care whether or not their team wins the next game, and the next championship. As long as they win, that’s all that matters.

An infinite game player cares about stats like the ~42,000 US city parks with basketball hoops. They care that ~40% of 13-17 year olds regularly play pick-up basketball, and the ~18,000 US high schools that sponsor basketball programs.

Many competitive pursuits die as a finite games because they are dominated by an early elite who are hostile to newcomers and casuals. They choose winning smaller victories over competing for a larger outcome.

Venture capital, the success of Silicon Valley, and much of today’s technological progress, was built on an infinite game: The pursuit of abundance through innovation, rather than simply dominating the status quo.

When an investor (either GP or LP) says indiscriminately that VC does not need more capital, they are implicitly using a finite game lens. They prefer that competition is restricted, and cannot see how that also limits the scale of opportunity for the category as a whole.

In the US, this attitude is becoming a problem as boutique firms are displaced by agglomerators. While the two aren’t in direct competition for LP dollars, the environment is increasingly defined by the participants with the most influence.

In Europe, this attitude is an entrenched problem. European venture capital did not emerge from an infinite game mindset as it did in the US. For all the anecdotes about Europe’s merchant banks, venture capital is an import that has quickly been seized by opportunists. This is why Europe’s venture capital scene has remained relatively small, at a cost to growth and prosperity. There has never been a vision for abundance.

City Parks for Entrepreneurship

If you want to take an infinite game approach to venture capital, you need to care that entrepreneurship is accessible, and that the interface between capital and talent is healthy.

To the agglomerators, this interface is addressed by scout programs where ambitious young adults seek startups that fit a pattern — as the incentives are to optimise for partner approval. So, more capital flows into SF/NY, Stanford and Harvard Grads, ex-Mag7 employees, AI tools, etc. The pool of opportunity narrows, but you aim to win more of it.

To the boutique investors, this interface is addressed by scouring college campuses and builder communities. They are looking for outliers; the people with ideas so outlandish that it may not have even occured to them to seek investment yet. The pool of opportunity grows, and you may win more of it.

The former is obviously a finite game. The latter is obviously an infinite game.

If the goal is (as commonly stated) the pursuit of abundance through progress, venture capital is implicitly an infinite game and we should care deeply about the entrepreneurial equivalent of city park basketball courts; distributing awareness, access and opportunity as widely as possible.

The fact that so much of the industry is focused on gatekeeping and exclusivity is an obvious signal of distress.

Rothenberg’s Paradox

A paradox in this story is that the scale of capital going to the finite game is much larger, and is growing more quickly.

How then is that the finite game?

This reflects what we might call Rothenberg’s Paradox: any successful infinite game creates opportunity for rent-seeking via finite game players. The scale of capital becomes the central opportunity, like a snake eating its own tail.

For now, venture capital maintains the illusion of a booming industry with growing opportunity — while it’s really just getting better at financial engineering and wealth extraction.

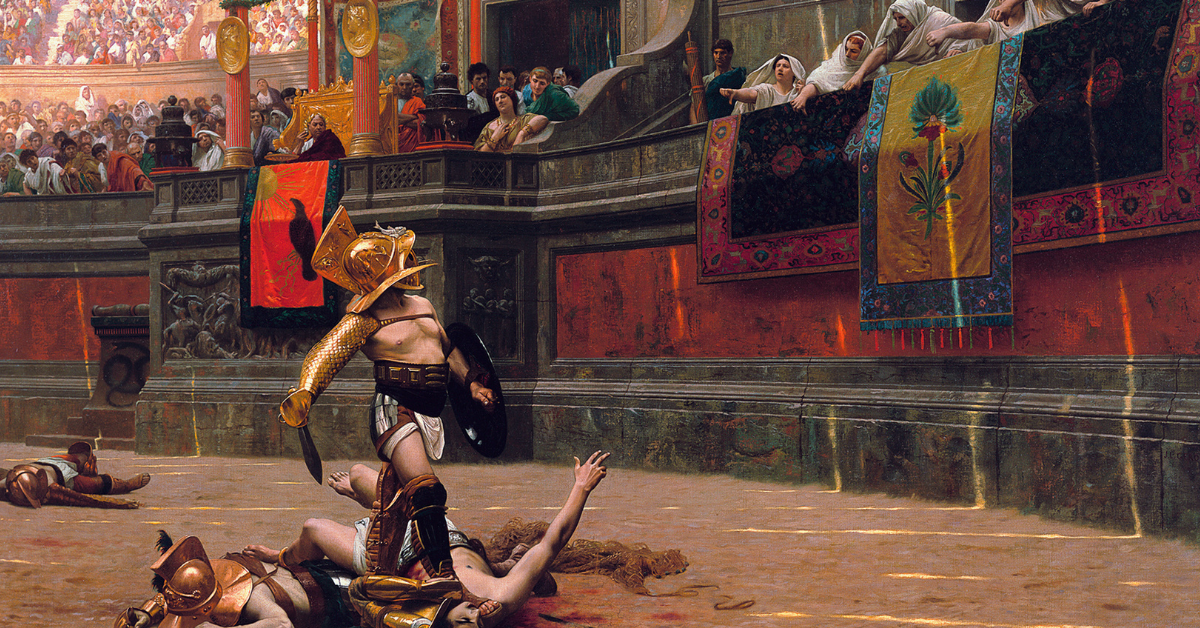

(top image: “Pollice Verso”, by Jean-Léon Gérôme)

Leave a Reply