Venture capital is a pyramid, not a barbell

With the need to coordinate capital across successive rounds of funding, venture capital is functionally pyramid-shaped.

In theory, you start with small Seed funds, progressively larger funds through the Series rounds, and the largest pools of institutional capital for companies on the brink of exit.

This is mostly explained via crude “fund returner” math, where each investment is expected to be able to return at least 1x of the fund based on the round’s entry price.

This arrangement defies the pattern of most maturing asset classes, where there is an emergent “barbell distribution” of small specialists and large generalists, for three main reasons:

- The (theoretical) need for a spectrum of different fund sizes to meet the range of capital requirements across the various stages of growth and funding.

- The lack of independence, as boutique firms do not offer meaningfully different exposure, as they rely on follow-on capital from large firms for their portfolio companies.

- The LP relationship, as boutique firms are often selected and capitalised by large firms for the purpose of generating market intelligence and deal flow.

In contrast, consider the division of PE:

Small and large are competing strategies. Boutique firms focus on small to mid-cap opportunities for growth potential while large firms focus on driving efficiency in large-caps. Boutiques may exit an investment to a large firm, but they do not share exposure.1

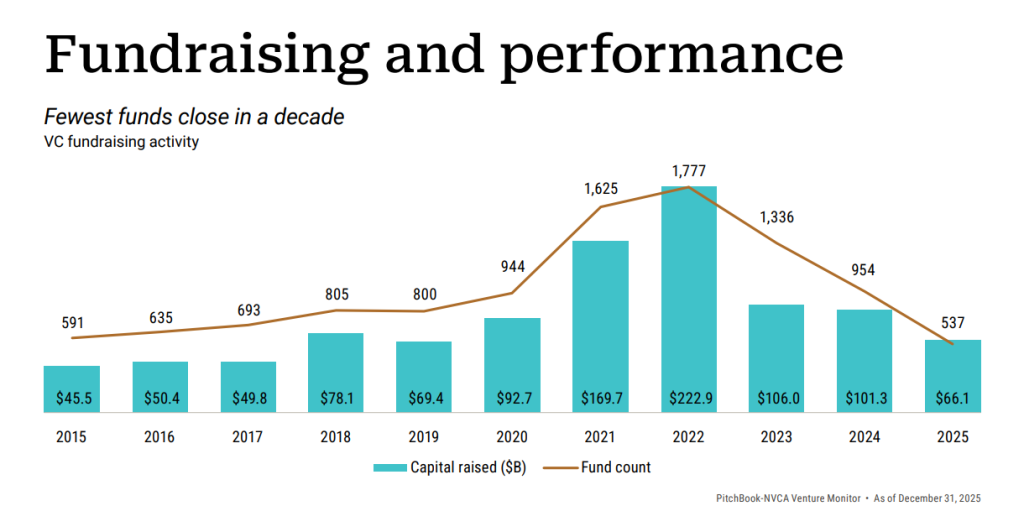

So, what is referred to as the “barbelling” of venture capital is actually just an increasing top-heaviness, as repeated cycles of consolidation hit everyone except the whales and a handful of annointed/legacy boutique firms.

It’s not the shifting of the distribution outwards, towards each end of a spectrum. It’s the shift of capital upwards, moving it out of the “base” of boutique managers into the hands of large firms. Like a dangerous game of Jenga.

The resulting problem is that small firms are being consumed by the large fund strategy through their reliance on them as providers of both follow-on and LP capital.

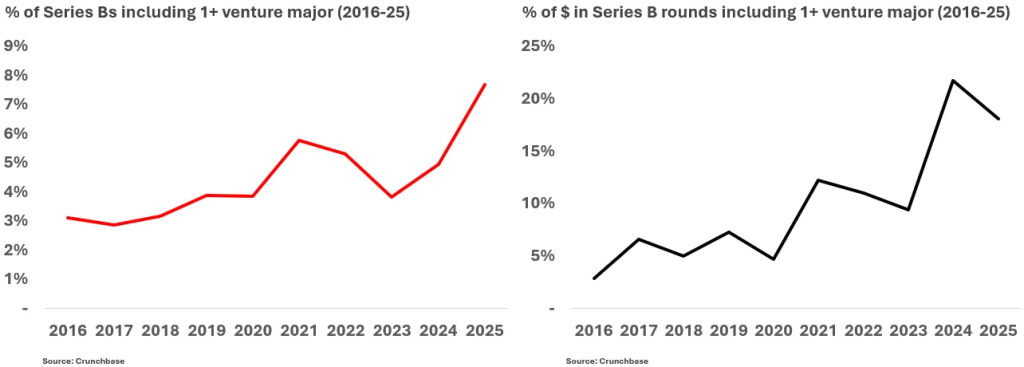

Indeed, if you invest in a company today, who do you hope does the Series B? Increasingly, it’s a large firm.

A Seed firm must now prioritise companies with the potential to be fund returners for >$1B funds (especially when combined with LP enmeshment), which is a significant adjustment in strategy — and a major limitation.

This implies a smaller pool of relevant opportunities.

More capital being raised on shorter horizons.

More dilution.

Stolen Growth

The growth in VC funds, chasing the incentives of larger LPs and the associated fee income, has necessitated larger exits.

How can an investment strategy manifest larger exits? Simple, hold them longer and feed them with more capital, which solves the allocation problem as well.

Effectively, this is growth transferred from public markets.

Most venture investors (particularly those without many exits to their name) would have you believe this is good; that public markets are burdensome and bad for innovation.

Not only are they wrong, they are obscuring the extreme cost of private capital, and the misaligned incentives in private markets (myopic focus on revenue growth).

In the past, venture-backed companies could exit at a range of sizes and still yield excellent, profitable outcomes. Today, the dumb assumption is that exits need to be huge, which conveniently fits the interest of large firms.

For everyone else, going public is beneficial. It’s good for unprofitable companies, and it’s good for innovative companies. It’s just not good for venture capital, because the large firms need somewhere to put their money.

“We find that less profitable companies with higher investment needs are more likely to IPO. After going public, these firms increase their investments in both tangible and intangible assets relative to comparable firms that remain private. Importantly, they finance this increased investment not just through equity but also by raising more debt capital and expanding the number of banks they borrow from, suggesting the IPO facilitates their overall ability to raise funds.”

Access to Capital and the IPO Decision: An Analysis of US Private Firms

To be clear about the consequences of this:

There are companies that could have achieved modest exits (great for small firms), which would have then compounded in public markets for decades. Many have been denied that opportunity because they seemed unsuitable for the large firm model of venture capital.

The implicit justification is that private markets are a better environment for growth, and so if a company isn’t suitable for private market investors it couldn’t become a good public markets opportunity either. This is incorrect on all counts.

Many companies will be able to hit IPO-ready metrics with less private capital than is force-fed to them today, and will fare better in public markets.

Indeed, there’s a point at which extended time in private markets will erode the appeal of a company for public market investors.

Thus, the increasingly top-heaviness of venture capital is:

- Limiting the range of companies that might be offered venture capital to begin with.

- Holding them private for longer, to absorb more capital and generate markups.

- Producing worse quality exit outcomes for everyone on the other end of the trade.

This is bad for founders, it’s bad for innovation, and it’s bad for the market. The only beneficiaries are those extracting fees..

Two years ago I suggested that venture capital needed to embrace divergence; to split cleanly into small and large funds that are in competition for LP dollars rather than enmeshed with each other.

This change would allow venture capital to grow towards the “barbel” distribution of mature asset classes, and would allow for targeted regulation that eased the burden on small firms while increasing scrutiny on the problematic large firms.

The case for this grows clearer every day.

(top image: “The Sea of Ice”, by Caspar David Friedrich)

(title inspired by a conversation between Bryce Roberts of Indie and Michael Dempsey of Compound)

- A relationship I’ve argued that VC should emulate. [↩]

Leave a Reply