Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome

Charlie Munger

One of the most thought-provoking articles in venture last year was Jamin Ball’s “Misaligned Incentives“, in which he talked about the difference between 2% firms and 20% firms.

The 2% firms are optimizing for deployment. The 20% are optimizing for large company outcomes. There’s one path where the incentives are aligned.

Jamin Ball, Partner at Altimeter Capital

The article was significantly because it was represented a large allocator acknowledging the issue with incentives in private markets. Not a novel take on the problem, but resounding confirmation.

Ball stopped short of suggesting an alternative incentive structure, which was probably wise given visceral opposition to change. Many influential firms have grown fat and happy in the laissez-faire status quo of venture capital.

Ball — like many people, myself included — framed carried interest as the ‘performance pay’ component of VC compensation. The problem is implicit: we have therefore accepted that fees are not connected to performance.

For decades, we’ve accepted the wisdom that carry = performance, and fees = operational pay. Nobody thought to question that reality.

Unfortuantely, for many firms (and certainly the majority of venture capital dollars under management), carry is a mirage. It exists so investors can pretend that performance is a meaningful component of their compensation while they continue optimising for scale.

European Waterfall vs. American Waterfall

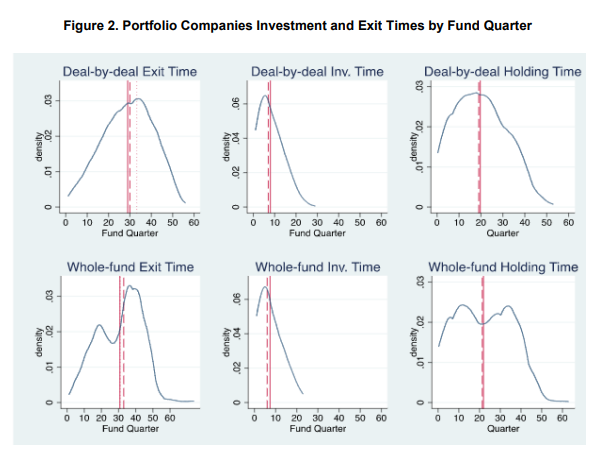

European waterfall is a whole-fund approach to carry, whereby GPs don’t receive carried interest until LPs have had 1x of the fund (plus a hurdle) returned to them. American waterfall operates on a deal-by-deal approach, with a clawback provision if the fund isn’t returned (plus a hurdle).

We know the american waterfall model (while imperfect) has historically outperformed, and yet the european waterfall has become standard. Venture capital has biased towards the ‘LP friendly’ approach to carried interest, even though it reduces their carry income, because it enables more easily scaling funds.

We find strong evidence that GP-friendly contracts are associated with better performance on both a gross- and net-of-fee basis. The public market equivalent (PME) is around 0.82 for fund-as-a-whole (LP-friendly) contracts but is over 1.24 for deal-by-deal (GP-friendly) contracts.

Paying for Performance in Private Equity: Evidence from VC Partnerships

In summary, the problem is not that VCs have picked fees over carry as the more attractive incentive, it’s that carry has been used as a smokescreen for the exploitation of fees.

Consider these few points, from the perspective of a seed GP:

- If you charge a fee to manage the fund, you should not raise a successor fund without a serious step-down in those fees. Otherwise, what are you being paid for?

- You should not charge management fees on investments you’re no longer truly managing. If you have no meaningful influence over a company in your portfolio, what are you being paid to do with it?

- Indeed, if you’re no longer truly managing those investments, it’s incumbent on you to sell enough of your stake to lock-in a reasonable return when the opportunity is available.

- If you raise a larger subsequent fund, you should be able to explain how that strategy allows you to extract a similar level of performance from a larger pool of capital. Otherwise, how can you rationally justify a larger total fee income?

- Everybody knows that markups are bullshit. If you want to raise a second fund, get at least 2x back to your LPs through secondaries first. DPI is the only proof that there’s value in your investments.

None of this should be surprising or even unintuitive, and yet…

- Successor fund step-downs are remarkably uncommon.

- Most US funds still do fees on total comitted capital, not even fees on invested capital, never mind fees on actively managed investments.

- GPs are being paid to hold companies when they’d be better off securing an exit, or propping up zombie portfolio companies just to continue harvesting fees.

- Few GPs have a sophisticated view on early returns, with most still focusing on MOIC rather than IRR and assuming late-stage price inflation will continue.

- VCs expect founders to present a coherent pitch covering growth strategy and the implicit capital requirements. The LP-GP relationship is far cruder.

- The whole venture ecosystem knows markups are barely worth the paper they are written on — and yet these incremental metrics continue to drive fundraising activity.

Over the past 15 years, LPs have become so preoccupied with getting into the hottest name-brand funds that there has been little scrutiny given to the fundamental logic of terms.

Today, with the market bifurcated into ‘venture banks’ and traditional venture capital, there is the opportunity to return to first principles.

We can start by examining the extremes:

Ending the charade; 100% fees

In an entirely fee-based environment, without carry as a smokescreen for bad actors, fees would likely be more clearly connected to performance — addressing the concerns laid out above.

This has the benefit of being a more predictable approach to compensation, likely attracting more responsible fiduciaries and level-headed investors. Less swinging for the fences, and more methodical investing and steady DPI.

However, it would also mean losing an important minority of brilliant investors who are genuinely motivated by carry.1

Ending the AUM game; 100% carry

In a scenario where investors only ‘eat what they kill’, performance would matter so much — across so many dimensions — that VCs would have to very quickly develop better practices on portfolio management and liquidity.

Of course, the downside is that compensation would be heavily backloaded, with no compensation for the early years of deploying capital and developing exits. A deeply unhealthy barrier to entry for emerging managers.

What’s interesting about these two edge-cases, on opposite ends of the spectrum, is that both produce the same outcome: a greater level of professionalism, with a more sophisticated view on portfolio management and liquidity than we see today.

Clearly, neither extreme is a good option and the ideal is somewhere in the middle — with both fees and carry in the mix. However, central to incentivising better outcomes is an end the fee exploitation game, with two key realisations for LPs:

- Fees must be connected to performance, in that a GP should not be able to raise another fund if they have not yet demonstrated concrete performance.

- The only meaningful demonstration of performance is DPI. Fortunately, as the market embraces secondaries, it’s possible to generate meaningful DPI much sooner.

Venture capital needs to evolve alongside more distant exit horizons by making better use of secondary liquidity, more cleanly dividing the market into early and late stage strategies — which can each then better play to their strengths:

Indeed, some of the best early stage investors around today are already adapting to this reality:

The times that it’s easiest to sell into these uprounds, are probably the times you should think seriously about it if you’re a seed fund.

Mike Maples, Jr, Parter at Floodgate

We were able to take a 1x or a 2x of the entire fund off [the table] and still be very long in that company. That locks in a legacy, locks in a return, and shortens the time to payback.

Josh Kopelman, Co-Founder of First Round Capital

For funds like [mine], selling stock of private startups to other investors will be “75% to 80% of the dollars that [limited partners] get back in the next five years.

Charles Hudson, GP at Precursor

You’re told ‘illiquidity is a feature, not a bug’ and ‘let your winners ride.’ But when the physics of the model shift, you often need to with it.

Hunter Walk, Partner at Homebrew

I’ve been doing the ‘anti-VC’ strategy of selling my winners […] When a company gets overvalued, and I can no longer underwrite a 10x.

Fabrice Grinda, Founding Partner at FJ Labs

You sell at the B, and you actually — for us, with the way our math worked — could have a north of 3x fund. But I also wouldn’t want to give up the future upside. We actually ran that through the C and the D. The big ‘Aha’ for me was that selling at the Series B, a little bit, was actually very prudent for a couple of reasons.

Charles Hudson, GP at Precursor Ventures

With all of this in mind, it no longer unreasonable for LPs expect something like a 2x return on their capital by year 6, and for VCs to raise new funds based on hitting that 2x target. Ensuring a decent return (on an IRR basis) for their LPs while companies are still within their orbit of influence.2

Unsurprisingly, proposals to fix fee income are unpopular, and not only with those who profit from the status quo. There is a lack of systems thinking which would allow participants to grasp the interconnected factors which shape outcomes, and see the opportunity for change.3

Indeed, many of the objections are based on silly recursive logic, e.g.

- secondaries aren’t a good market ➝ because they’re only used to sell poor quality assets ➝ so they’re not a good market

- returns in venture come from a few giant outcomes ➝ so we hold to IPO ➝ so more value accrues to a few survivors ➝ so most of the returns come from a few giant outcomes

- you can’t get liquidity on markups➝ because they’re optimised for fees not liquidity ➝ so markups aren’t liquid

In essence, power law and illiquidity are both absolutely realities of the venture strategy, but both have also been used to excuse and entrench suboptimal practices.

The Opportunity of Secondaries

A common misconception: the value of investments increases consistently (even exponentially) over time, so GPs should always hold to maturity. This idea has played a significant part in slowing down the use of secondary transactions. It’s not really true.

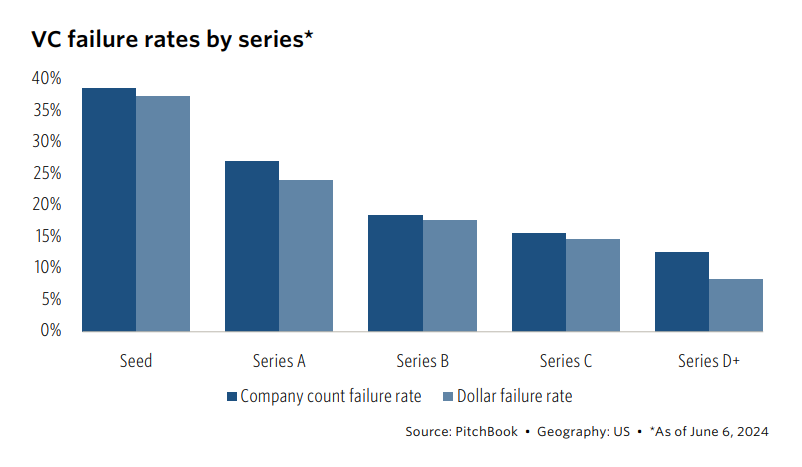

Investments often don’t increase in value. Quite often, they fail outright. Failure rate does reduce over time (39% at seed, 13% at series D), but it remains significant throughout.

To quote the brilliant thread from Rob Go:

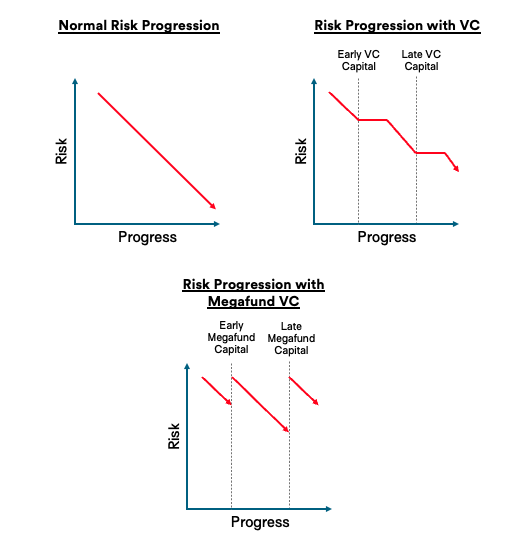

Typically, you think of a series A startup as less risky than a seed startup, and a series D startup as less risky than a series A startup. This is often true, but because VC dollars both add and remove risk, the move down the risk curve is less linear.

This is especially true for ‘the biggest winners’ who are often absorbing huge amounts of capital from the ‘venture banks’:

But in recent years, this picture has been skewed even more, especially if the capital raised comes from a mega VC fund. At each funding round, there is a significant re-risking of the startup, to the point that you are not moving meaningfully down the risk curve for a long long time. And even at a late stage, a mega funding round can bring you right back up to the point of maximum risk.

These rounds are also often highly dilutive; particularly with the proclivity of large firms to ignore pro-rata and cram-down early investors.

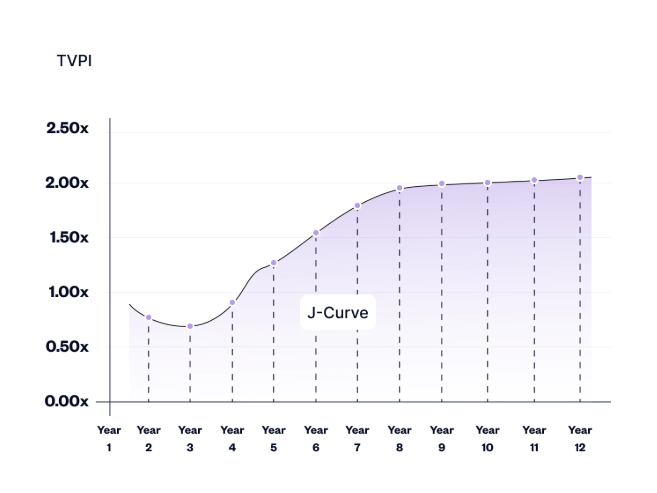

So, in an absolute sense, there is a sustained risk of failure which slowly concentrates portfolio returns into fewer companies over time, which will decelerate TVPI growth (or even turn it negative).

On top of that, there are often terms included in later rounds which mean that shares held by early investors become relatively overvalued. Particularly, IPO ratchet clauses and automatic conversion vetos. Thus, even if the theoretical TVPI of a seed fund remains flat, in reality it may be falling:

“In November 2015, Square went public at $9 per share with a pre-IPO value of $2.66 billion, substantially less than its $6 billion post–money valuation in October 2014. The Series E preferred shareholders were given $93 million worth of extra shares because of their IPO ratchet clause. This reinforces the idea that these shares were much more valuable than common shares and that Square was highly overvalued.”

Squaring Venture Capital Valuations With Reality

Looking at AngelList data, the best time for a fund to sell (on an IRR basis, and ignoring the clauses above) would be year 8 — with value concentrating (but not really net expanding) in years 9 through 12.

That means the typical investment (assuming a 3 year deployment period) would be best positioned for a (partial) sale in years 5-7. Considering this, it’s difficult to make the case that GPs should be holding 100% for the ultimate outcome, every time. If they do, they are concentrating their risk without necessarily improving the portfolio outcome.

To take this a step further, we could assume in a more rational market, less dominated by hype (more secondary activity driving more pricing tension, fewer bullshit markups), the illustrated TVPI would flatten out more gradually — so less of an obvious time to sell.

In short, the story here is not about opportunistic secondaries to drive better IRR. The real case to be made is for a comprehensive secondaries strategy, and opportunistic holding. For too long, there has been ideological friction around secondaries which has held back venture performance and enabled some very bad habits. It’s time to change that.

If there’s a chance to wipe the slate clean for venture capital, for LPs and GPs to return to first principles on compensation, incentives and ideal outcomes — to begin aligning venture capital with a high-performing meritocracy — it’s here, today.

Ironically, innovations in venture capital haven’t kept pace with the companies we serve. Our industry is still beholden to a rigid 10-year fund cycle pioneered in the 1970s. As chips shrank and software flew to the cloud, venture capital kept operating on the business equivalent of floppy disks. Once upon a time the 10-year fund cycle made sense. But the assumptions it’s based on no longer hold true, curtailing meaningful relationships prematurely and misaligning companies and their investment partners.

Roelof Botha, Managing Partner of Sequoia Capital

[EDIT 24/06/2025: Added a quote from Charles Hudson]

- Listening to Jack Altman’s podcast with Josh Kopelman of First Round helped change my mind on this. [↩]

- I believe a 2x return is not an unreasonable target, but the market would adapt if it were. [↩]

- This observation is based on the feedback I had to an initial proposal. [↩]

Leave a Reply