The two faces of what we sometimes call venture capital, and the cognitive dissonance they create.

This blog started out as a place to write about the intersection of science fiction and technology. The first article about venture capital, and the opium of consensus, emerged from watching VCs herd into thinly-veiled crypto scams in the name of “web3“.

The influence of consensus remains poorly understood, and the subject of distracting counterfactuals, despite being widely discussed for as long as “investor” has been a profession.

Words must have meaning

Venture capital is the practice of identifying nascent business opportunities with radical potential; the application of process to extract outsized value from extreme idiosyncratic risk.

In this context, venture capital is clearly not a consensus-oriented discipline. Both theoretical and quantitative perspectives support this reality; the intention, goals, behavior and performance.

We find that consensus entrants are less viable, while non-consensus entrants are more likely to prosper. Non-consensus entrepreneurs who buck the trends are most likely to stay in the market, receive funding, and ultimately go public.

The Non-consensus Entrepreneur: Organizational Responses to Vital Events

Simply look back at the early-days of venture capital’s largest outcomes, where the majority did not have investors competing for access, driving up the price. Fundraising was a struggle for those founders, and in that struggle was the opportunity for those on the other side of the table.

It’s very hard to make money on successful and consensus. Because if something is already consensus then money will have already flooded in and the profit opportunity is gone. And so by definition in venture capital, if you are doing it right, you are continuously investing in things that are non-consensus at the time of investment.

Marc Andreessen, a16z

Indeed, if consensus were to play a meaningful role in venture capital, it would fail on the only two things it sets out to achieve:

- Maximise ROI for LPs through idiosyncratic risk

- Finance the development of novel innovations

In addition, there is no such thing as a downstream supply of “non-consensus capital”. If you fund non-consensus companies then you have to be able to support them to the point where their potential is obvious and larger/later generalists can be convinced. It’s paradoxical to believe that other investors will share your non-consensus viewpoint.

Cognitive dissonance

The root of the confusion about consensus (and entry price, portfolio construction, attention, relationships…) is the mixing of two different private market strategies. One is venture capital, and the other is something else that just falls into the venture capital allocation bucket.

This other strategy emerged in the period from 2011 to 2021, enabled by low interest-rates, as described by Everett Randle in “Playing different games“:

Tiger identified several rules / norms / commonly held ideas in venture/growth that are stale & outdated and built a strategy to exploit the contemporary realities around those ideas at scale.

Everett Randle, Kleiner Perkins

The capital mechanics of this strategy were explained further by Kyle Harrison, in “The Unholy Trininty of Venture Capital“:

So you have massive capital allocators looking for places they can farm yield and they don’t want to be slinging hundreds of $30M checks. Capital agglomerators represent the perfect solution. Hit your 7-8% yield target, be able to park $250M a pop without being the majority of the fund, and sit back and relax.

Kyle Harrison, Contrary

Versions of “bigger/faster/cheaper capital” have since been employed by other multi-stage platform firms, and the consquences are dramatic:

- The platforms pay a premium between 63% and 171%, depending on stage.

- The most active platform led 61 Series A rounds since 2022, compared to 12 by the most active “boutique” firm.

- The platforms both scaling up and increasingly concentrating on “obvious” investments, e.g. AI, or San Fransisco/Software.

If success in venture capital is driven by non-consensus investments, in less competitive ecosystems with more rational pricing, why would an investor pursue a strategy directly to the contrary?

The answer is indicated in Martin Casado’s episode with Harry Stebbings, in which he described missing the category winner as the greatest sin of investing.

This hunger to capture the most extreme “power law” category leaders is a requirement of the exit math involved in multi-billion dollar funds. Consequently, these platforms also raise substantial early-stage funds to index any emerging theme, putting an option on the future of those companies.

A mega-VC with $5-10B annual funds is really searching for only one thing: a company they can pile over $1b into with a potential for 5-10X on the $1b. With this, seed fund is inconsequential money used to increase the odds of main objective.

Bill Gurley, Benchmark

The startup industrial complex that has emerged is not optimised for non-consensus investing, and nor does it need to be. Investors at these platforms are hired to compete and win in known areas — and have attitudes to match:

Successful startups fit into a mold that investors understand, and that more often than not those startups attracted meaningful competition among top investors.

Martin Casado, a16z

If a company has tons of hype and seems overvalued, don’t run away. Run towards it. Hype is good. Means they’ll raise, exit at higher valuation. And the price likely won’t feel overpriced after the startup exits.

Andrew Chen, a16z

The output is a rough index of high-growth private technology companies. The platforms are harvesting the beta from innovation, rather than finding the alpha in outliers. Even the giant outcomes become so well/over-priced that their returns risk converging with benchmarks.

Categorically, this is not venture capital in any meaningful sense.

The only reason we call this venture is because LPs need to call it venture so CIOs can hit annual allocation targets they promised boards. This is venture allocation, not venture returns.

Will Quist, Slow

Venture Alpha and Venture Beta

To repeat a point already well-hammered, the platform strategy is entirely different, with a different LP base, a different return profile, and different rules.

The difference between the Andreessen quote above, and the more recent quotes from Chen and Casado, is simply that in 2014 Andreessen Horowitz was a venture capital firm. Today it is an asset manager, an RIA with a multi-stage platform strategy, perhaps best described as a venture bank.

Many VCs have sought to assimilate “tier 1” multi-stage behavior, acting out what they believe LPs and peers expect to see despite the fundamentally incompatible models. This herding around identity and behavior reflects the extreme level of insecurity in venture capital, a product of the long feedback cycles and futility of trying to reproduce success in a world of exceptions.

Venture Banks

There is no harmony with venture capital, and the behaviors of these platform investors should not be emulated by venture capitalists — whether or not they also call themselves venture capitalists.

To put a point on this: The platforms explicitly benefit from consensus and price inflation. Both are toxic to venture capital.

As long as both strategies are discussed under the banner of venture capital, we’ll keep wasting time on pointless debates about markets and incentives, and investors will keep making dumb, confused decisions.

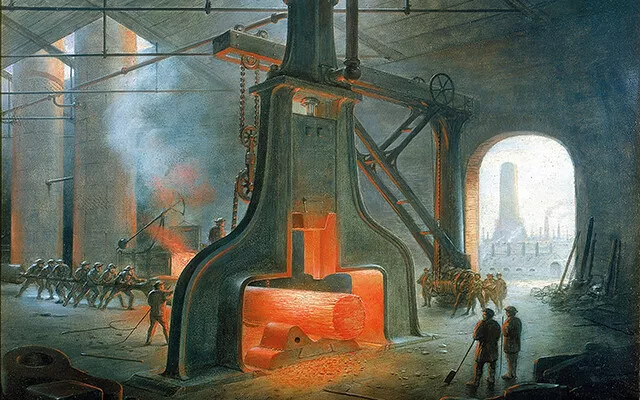

(top image: A Steam Hammer at Work, by James Nasmyth)

Leave a Reply