The history of human progress is predicated on the history of efficient risk capital formation.

WIll Manidis

The story of venture capital (and its precursors) is a story of risk. You can take this back as far as you like, from ARDC to Christopher Columbus. From whaling expeditions to space exploration.

Risk is the product.

And, essentially, it boils down to this calculation:

The merit of any investment depends on whether the probability of success multiplied by the forecasted return is greater than the cost.

- Investments that are perceived to have a high probability of success attract a lot of competition.

- Investments that are perceived to have a low probability of success attract very little competition.

Venture capital is at the far end of this spectrum, where the ‘skill’ is in recognising when the market has mispriced risk because an idea is unconventional rather than bad.

This brings us to the first category of risk in this conversation: idiosyncratic risk.

Idiosyncratic Risk

(the specific risk of an investment)

Idiosyncratic risk reflects the specific potential of an investment: the probability of success, and the assumed return if it is succesful.

Assuming you cannot change the probability of success or the assumed return, there are two ways to handle idiosyncratic risk:

- Making low probability investments profitable by diversifying away total failure.1

- Making low probability investments profitable by pricing the risk appropriately through valuation.

These are the two main levers of venture capital, which is focused on what Howard Marks refers to as uncomfortably idiosyncratic investments:

The question is, do you dare to be different? To diverge from the pack is required if you’re going to be a superior in anything. Number two, do you dare to be wrong? Number three, do you dare to look wrong? Because even things which are going to be right in the long run, maybe look wrong in the short run. So, you have to be willing to live with all those three things, different, wrong, and looking wrong, in order to be able to take the risk required and engage in the idiosyncratic behavior required for success.

Highlights from a conversation with Howard Marks

Idiosyncratic risk contrasts with the other main category of risk that investors must consider: systematic risk.

Systematic Risk

(broader market-related risk)

If idiosyncratic risk is typified by venture capital, then systematic risk is typified by index funds. Consider the extent to which index fund performance is influenced by individual companies versus major political or economic events.

Nevertheless, systematic risk is a consideration in venture capital, and there are two ways to handle it:

- Avoid consensus, where competition drives up prices without increasing success rate or scale.

- Avoid market-based pricing, where macro factors can drive up prices without increasing success rate or scale.

Exposure to systematic risk essentially destroys an investor’s ability to properly manage (and extract value from) idiosyncratic risk.

Alpha vs Beta

If we consider idiosyncratic risk as the source of ‘alpha’ (ability to beat benchmarks) in venture capital, systematic risk reflects the ‘beta’ (convergence with benchmarks).

A striking shift in venture capital over the last 30 years, particularly the last 15, is the extent to which the balance has shifted from idiosyncratic risk to systematic risk. This is a consequence of prolonged ‘hot market’ conditions, where consensus offers a mirage of success.

Consider a typical VC in 2025. They’re likely to be focused on AI opportunities, guided by pattern-matching and market pricing (aka, “playing the game on the field”). Investing, in this scenario, is reduced to a relatively simple box-checking exercise.

All of this implies significant systematic risk; the firm is riding beta more than they are producing alpha. This creates extreme fragility.

Systematic risk has always been a concern, but it has been amplified in recent years by cheap capital and social media. The herd has grown larger and louder; more difficult for inexperienced or insecure investors to ignore:

- Taking systematic risk means following the crowd. It’s an easier story to sell LPs, and there’s less career risk if it goes wrong as accountability is spread across the industry.

- Taking idiosyncratic risk means wandering freely. It’s tough to spin into a coherent pitch, and there’s more obvious career risk associated with the judgement of those investments.

Despite mountains of theory and evidence supporting idiosyncratic risk as the source of outperformance, it’s just not where the incentives lie for venture capital.

The Jackpot Paradox

There are fundamental consequences of the drift towards systematic risk in venture capital:

- The muscles of portfolio construction and valuation atrophy, as consensus-driven ‘access’ dominates behavior and idiosyncratic risk falls out of favour.

- The typical ‘power law’ distribution of outputs collapses as few genuine outliers can be realised from a concentrated pattern of investment.

- As returns converge on a mediocre market-rate, investors manufacture risk by feeding power law back into the system as an input, trying to create outlier returns.

- Success is further concentrated in a system that becomes increasingly negative sum overall.

This broadly summarises where we’re at today. A disappointing scenario that represents failure to the actual bag-holders on the LP end, failure to founders, and failure to innovation.

A lot of the blame falls in the lap of LPs. The low fidelity interface with GPs means that LPs have a general bias towards compelling stories which invite systematic risk.

Thus, venture capital is reduced to a wealth-destroying competition for access to the hottest deals, fundamentally at odds with the concept of ‘uncomfortably idiosyncratic’ risk and generating alpha.

Note 1: While idiosyncratic risk can be managed through diversification, diversification doesn’t necessarily produce greater systematic risk.

Note 2: Another way to look at the ‘venture bank’ versus ‘venture capital’ paradigm is that venture banks are deliberately set up to embrace systematic risk.

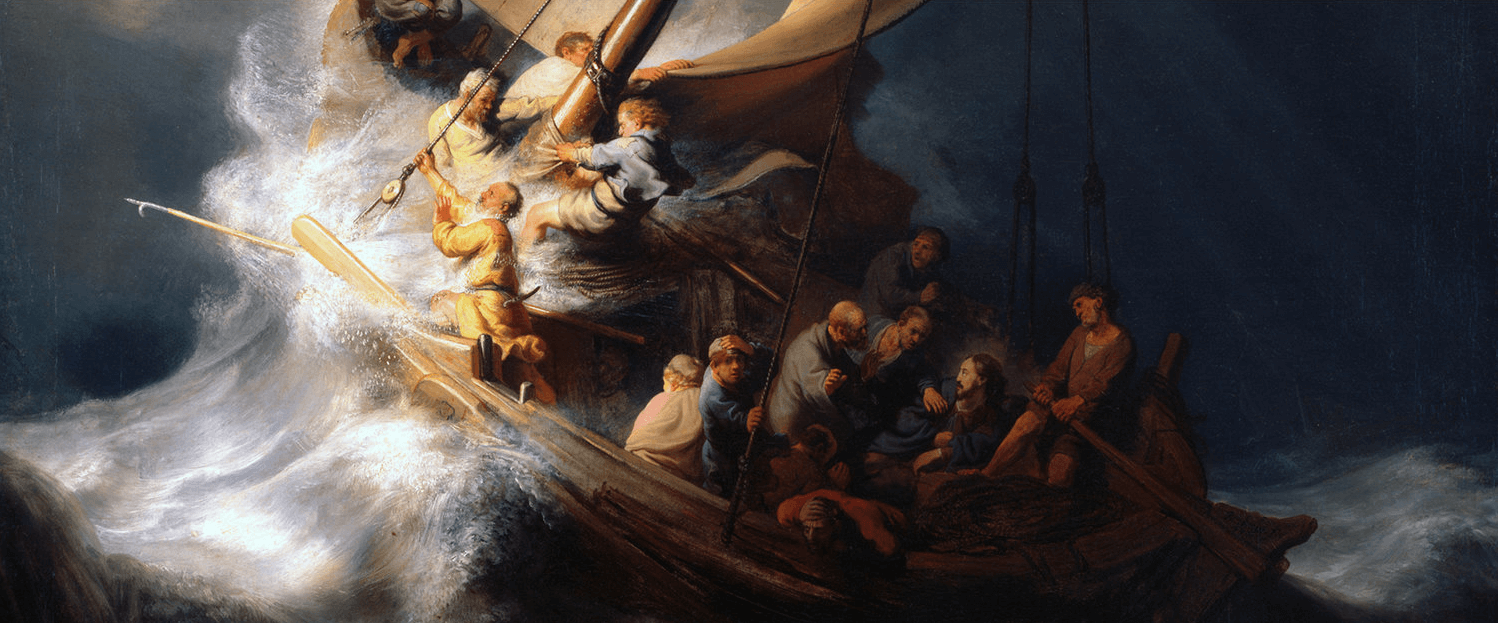

(image source: Rembrandt’s “Storm on the Sea of Galilee”, used on the cover of “Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk” by Peter L. Bernstein.)

Leave a Reply