“Small hinges swing wide doors”

Eric Bahn, Co-founder and GP at Hustle Fund

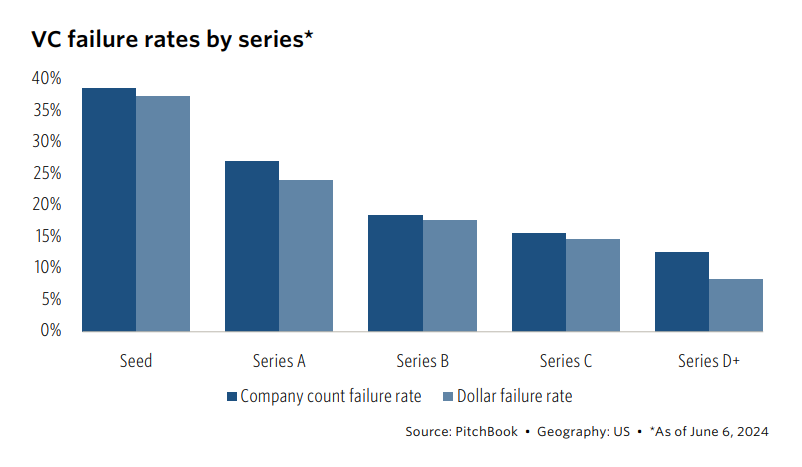

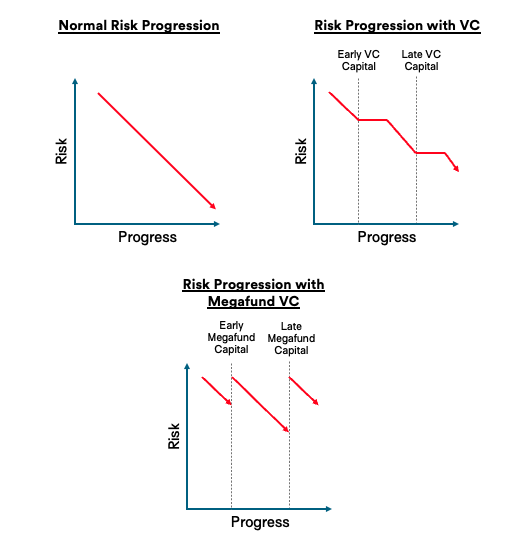

Consider this simple truth: All value created from Series A to exit is downstream of the first check. Without initial belief, the foundation of VC collapses.

This relatively thin slice of venture (by capital) is therefore disproportionately important. All future returns are directly attributable to the industry’s ability to surface new opportunities.

Despite this fundamental importance, venture capital is structurally rigged against origination:

- Origination is inherently a small check pursuit, as these ideas need minimal capital to validate propositions.

- Origination is primarily a small partnership or solo-GP pursuit, versus the consensus-building nature of large firms.

- LPs are biased against highly diversified VC strategies, particularly with the growth of Fund of Funds, which makes scaling an origination strategy more challenging.

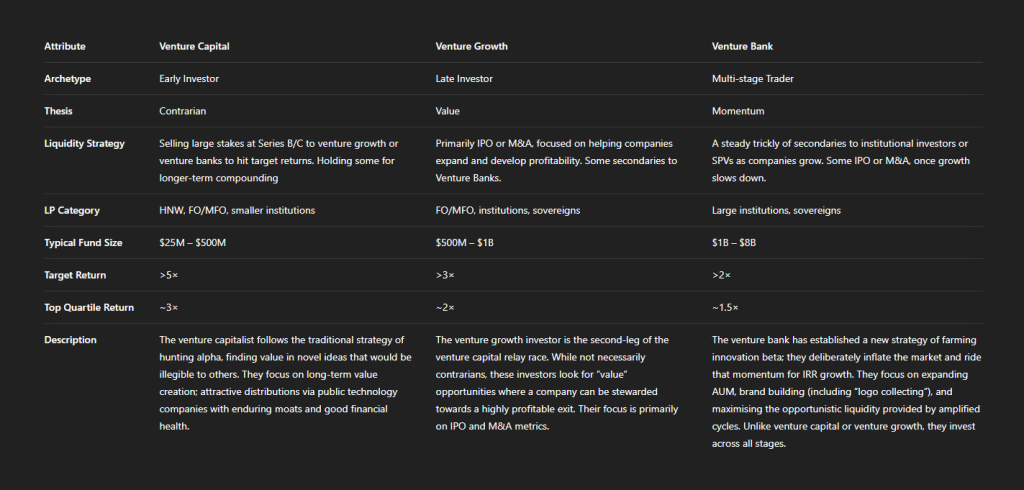

Thus, origination is the domain of smaller firms, with smaller funds. This runs contrary to the compensation incentives in venture capital, which push successful investors to raise larger funds and invest at later stages.

“In exploring its sources, we document several additional facts: successful outcomes stem in large part from investing in the right places at the right times; VC firms do not persist in their ability to choose the right places and times to invest; but early success does lead to investing in later rounds and in larger syndicates.”

The Persistent Effect of Initial Success: Evidence from Venture Capital (2020)

So, in addition to the existing problem of VC’s lack of institutional knowledge and high churn, good investors are often squeezed out of this origination focus if they wish to achieve greater scale.

Origination is the foundation on which all future VC returns are built, yet it is systematically underresourced and underallocated

You should be dubious of any venture capitalist that claims “there’s too much capital, and not enough good opportunities”.

You will never this claim from VCs focused on origination, who have to spend a distracting amount of time on their own fundraising — even when their track record is strong. Again, their size prohibits them from more easily raising from larger institutions.

This chronic misalignment sets the ceiling on what venture capital can achieve in returns and accelerated innovation

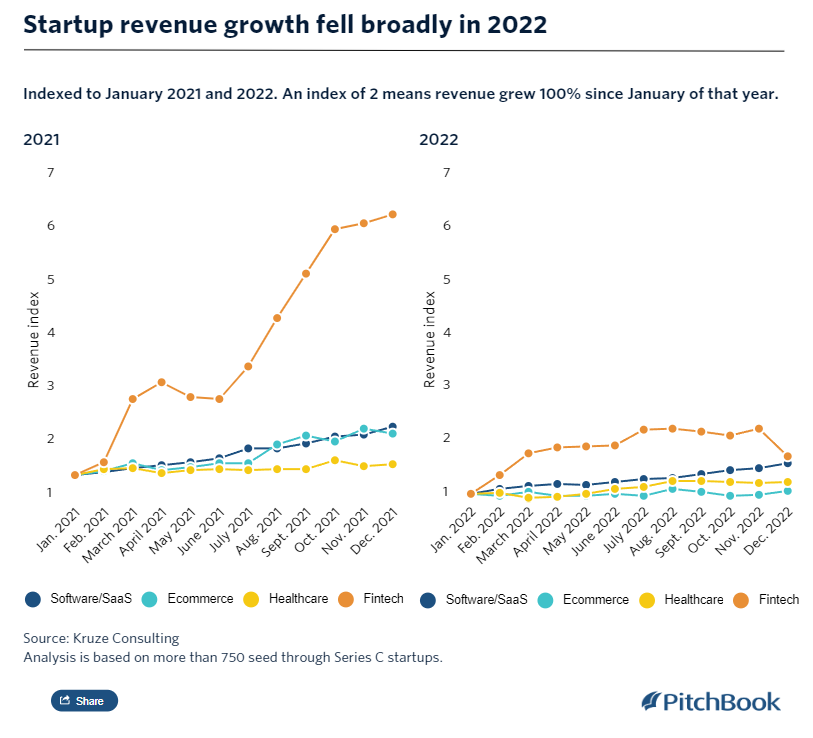

Multiple studies of the innovation ecosystem in Europe, and how funding is distributed by bodies like the EIF, have come to the same conclusion: Capital allocated to later stages does not solve the problem of underpeformance and slow progress.

Instead, shifting allocation earlier, to improve origination, without any increase in capital, has an effect equivalent to doubling the total capital pool.

It’s bad for innovation

Research indicates that origination struggles directly influence which startups are created: Founders who have a hard time finding VCs willing to write their first check end up pivoting to more generic ideas with lower information friction.

It’s bad for returns

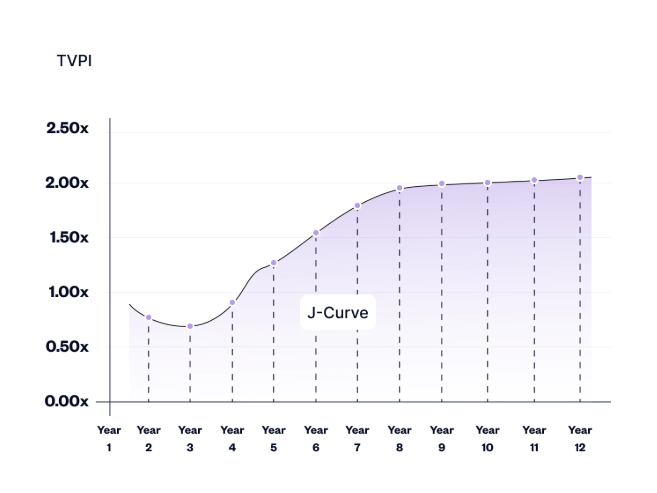

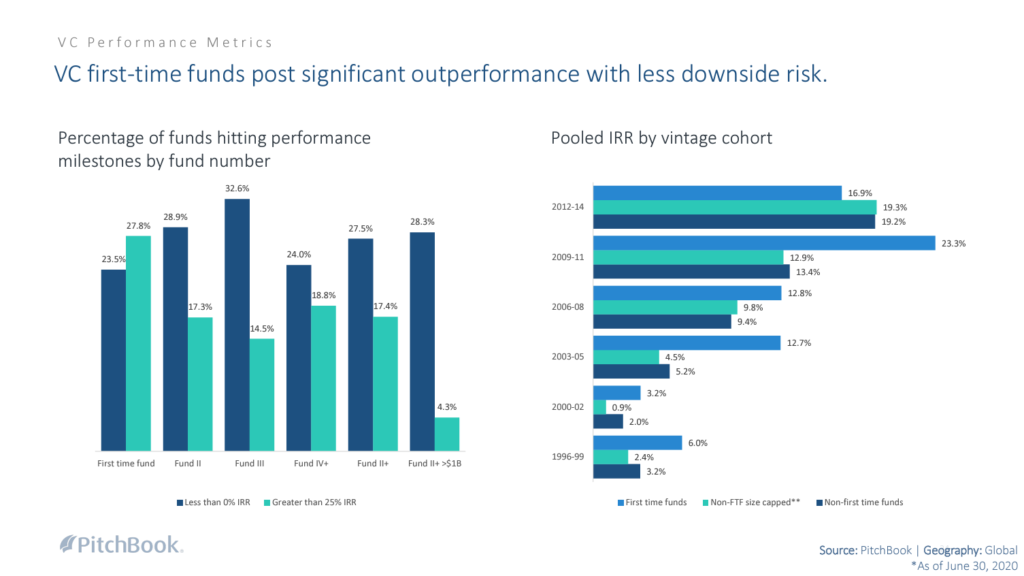

If all venture returns are downstream of origination, you would expect that a specific focus on origination would lead to outperformance amongst VCs. You would be right:

“The consensus in recent literature is clear: proactive deal origination is pivotal for achieving superior outcomes in venture capital investments.”

Where Are the Deals? Private Equity and Venture Capital Funds’ Best Practices in Sourcing New Investments (2010)

You’re not mad enough about VC incentives

Fundamentally, this issue will not be resolved as long as the incentives in VC mean the primary opportunity is to maximise fee income by optimising for proxy metrics.

There is very little intrinsic motivation for VCs to take excessive career risk on highly idiosyncratic ideas, which generate slower markups than consensus startups, in the hope that they may generate some carry a decade down the line.

In summary: Venture capital is structurally set up to pile capital into categories with low information friction, which is diametrically opposed to innovation.

You’d have to be brave, crazy or stupid to do anything else.

The brilliant exceptions

Fortunately, for everyone involved, there are a few mission-driven firms that have made it their business to focus on origination.

In today’s market, you’re either a lifecycle capital partner to founders, or you’re a niche operator originating unique opportunities for those who can be.

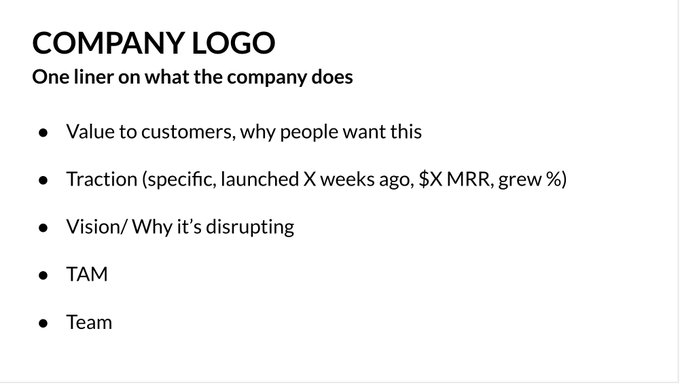

To originate deal flow, one needs some combo of:

– unique networks;

– top tier reputation in a niche; or

– uncommon levels of investment rigor for company stageAll of these help drive signal for the company, which is incredibly valuable in a noisy market.

Mike Annunziata, Founder and GP at Also Capital

They have each developed specific proactive strategies to find high potential opportunities, first — sometimes before there’s even a company to invest in.

- Firms that focus on early conviction and speed, like 1517 Fund and Hustle Fund — who write tiny inception checks to help prospective founders take the first step.

- Firms that focus on research and expertise, like Compound and Not Boring Capital — who find contrarian needles in consensus haystacks by processing vast quantities of information.

- Firms that focus on process and scale, like BoxGroup, Boost VC and First Round — who manage the greater idiosyncratic risk of origination with discipline and portfolio strategy.

- Firms that focus on community and talent density, like South Park Commons, and Entrepreneur First — who allow opportunity to manifest from pools of brilliance.

(They all share the key elements: community, research, process and speed.)

It’s hard to state just how much value can be attributed to these firms, and a few others like them. Relative to their size, they are responsible for a disproportionate amount of founder opportunity and downstream potential.

To understand the potential for these models, Y Combinator and Founders Fund are a good illustration of the same principles at scale. For a range of reasons, these two firms have broken out of the orbit of VC’s structural limitations.

To conclude, a quote from Danielle Strachman on 1517 Fund’s approach to origination, and some links to great conversations with the other firms above:

“We call it turning over rocks. It’s like, oh, I went to this campus and I found an interesting young person; we’re turning over rocks. You go to a hackathon and my favorite thing is to look for the young person who is staring off into space. They’re by themselves because they built their own thing. You go up and you talk to them and you’re like, whoa, okay, you are really super nerded-out on security and you’re talking to me like I should know what you’re talking about, and I have no idea. But we’re gonna talk for a while and we’re gonna figure this out.”

Danielle Strachman, Co-founder and GP at 1517 Fund

Interviews with the other firms mentioned:

- Adam Draper, Founder and MD of Boost VC on the Pathfinder podcast

- Danielle Strachman, Co-founder and GP at 1517 Fund on the Sourcery.vc podcast

- Josh Kopelman, Founder of First Round Capital on the Uncapped podcast

- Greg Rosen, Partner at BoxGroup on the Uncapped podcast

- Eric Bahn, Co-founder and GP at Hustle fund on Jason Levin’s podcast

- Matt Clifford, Co-founder of Entrepreneur First, on the World of DaaS podcast

- Ruchi Sanghvi, Founder and Partner at South Park Commons on the 20VC podcast

- Michael Dempsey, Managing Partner at Compound, on The Peel with Turner Novak

- Packy McCormick, Founder and GP of Not Boring Capital, on the Every podcast

(top image: “Supersonic”, by Roy Nockolds)