In a strange twist for an asset class built on patient capital and outsized returns, finding liquidity for investors has become a matter of urgency for VCs.

On the surface, this is a story about venture capital’s evolution and fund managers adopting more sophisticated liquidity strategies. Pry a little deeper, and you’ll find LPs reneging on capital commitments, pushing VCs to secondary markets and expressing disappointment with activity over the last few years. Now, some just want to cash out.

Gradually, and then suddenly

The average age of private companies exiting through an IPO has advanced from 7.5 years in the 1980s to 11 years in the 2010s, as both regulatory and macroeconomic factors have brought more capital into private markets.

The cash-rich environment allowed companies to grow into loftier valuations with relatively little scrutiny, while benefiting from the scrutiny of their public peers. For many this seemed like a winning strategy, with projected outcomes that were often jaw-dropping, and some VCs began talking about 15 year liquidity horizons. Significantly, there was no outcry from LPs; distant horizons were the name of the game, and the theoretical scale of returns bought a lot of patience.

Large private firms are thriving in part by freeriding on public company information and stock prices. Such firms’ astonishing ability to attract cheap capital may last only so long as public companies continue to yield vast, high-quality information covering a broad range of companies.

Elisabeth de Fontenay, Duke Law: The Deregulation of Private Capital and the Decline of the Public Company

So why the sudden pivot to seeking liquidity in the last two years? Why are investors now so concentrated on returning capital? Is there more to this story than interest rates?

Overheating the market

The basic proposition of venture capital is that LPs commit a certain amount of capital to a VC fund and are returned some multiple of that over the following decade.

There are two unique considerations for potential investors in venture capital:

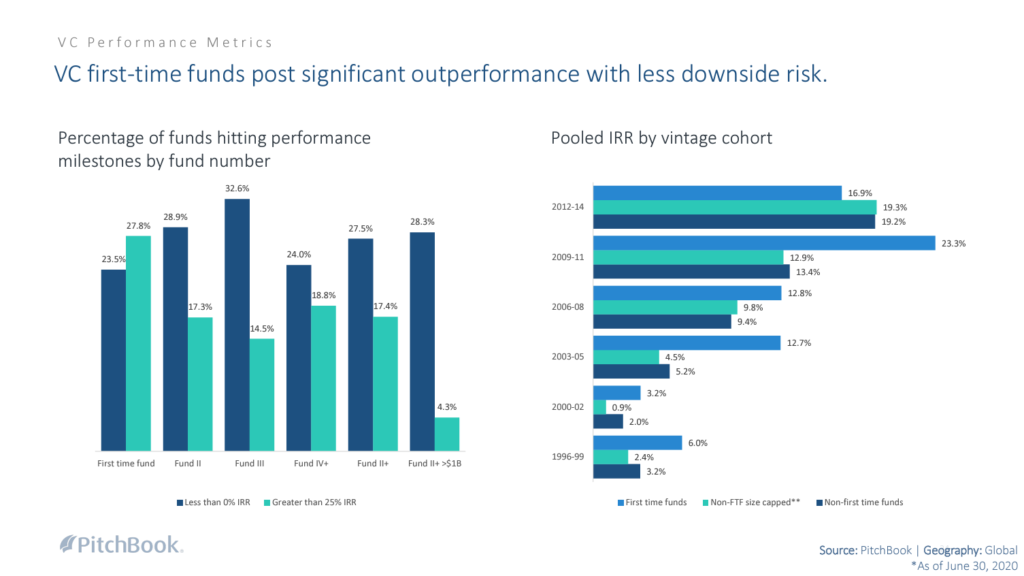

- VC firms will typically deliver weaker returns over subsequent funds, with many top performers being emerging managers with smaller funds.

- The asset class lacks a meaningful standard for measuring current fund performance, with firms ‘marking their own homework’ to some extent.

This combination makes it challenging to identify promising VC funds; track record is unreliable and performance is opaque. What remains for LPs is networks and trust, explaining why so much focus is put on relationships. These relationships, and over a decade of ultra-low interest rates, have allowed VCs to get away with longer periods of illiquidity and slipping rates of return.

The assurance offered, in place of returns, centred on the mounting theoretical value of venture portfolios. Venture-backed companies were raising vast sums from investors who thought of valuation as an ‘arbitrary milestone’ in the process. As long as the number kept going up with each new round, the investment looked good. This approach allowed VCs to raise ever-larger funds, extract more in fees, deploy more capital to inflate valuations further… and the wheel kept turning.

In theory, LPs were set for historic returns, as soon as those companies hit an exit.

The venture funding freeze

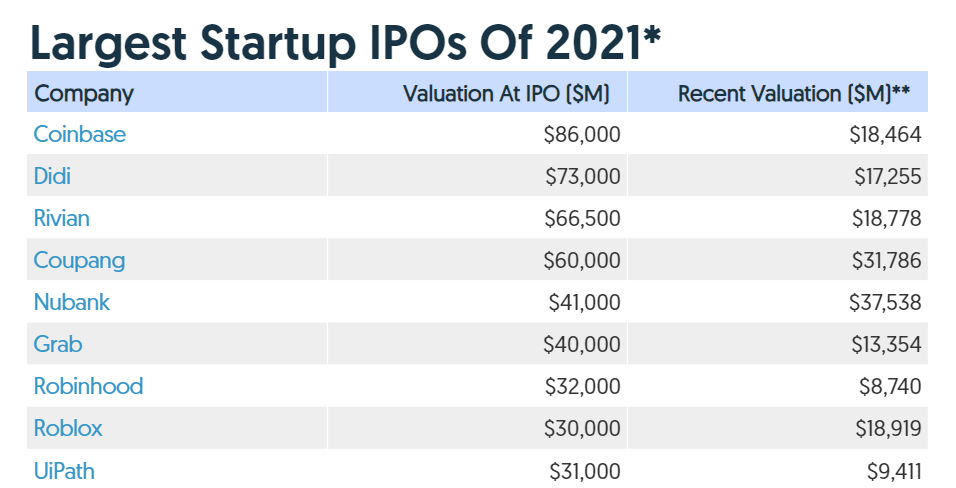

How many poorly-performing tech IPOs does it take to put public market interest on ice? In 2022, we found out.

While some point the finger at interest rates for spooking investors towards the end of 2021, the evidence of a correction was there from earlier in the year as many high-profile tech IPOs saw a rapid collapse in share price. There was a clear disconnect between tech valuations and a public market which no longer had faith in what they were being presented.

This was the consequence of venture capital’s exuberance. Shifting the focus to crude measures of current value had corrupted pricing discipline to the extent that exits were no longer viable. Any path to liquidity required coming to terms with huge markdowns, backtracking on the promised returns and damaging the trust of LPs.

To say that, in hindsight, it would have been a good idea to sell more stock in 2021 is to ignore the underlying irrationality. Had VCs been inclined to sell, valuations wouldn’t have been so high to begin with.

It was not that the strategy was bad, it was that there wasn’t one.

The path ahead for venture capital

VCs created this liquidity squeeze by exploiting an opaque market and increasingly divorcing price from value. This is precisely what needs to change in order to foster a healthy secondary market: greater transparency, discipline on valuation.

Specifically, a secondary market will only work if it is perceived to be where VCs sell their winners at a reasonable price, to account for shifts in risk profile outside of their portfolio focus. In this scenario, the incentives are built on transparency. Conversely, if the perception is that secondaries are for firms to offload companies that investors have lost faith in, then the incentives are built on obscuring or misrepresenting performance. That asymmetry leads to adverse selection and the slow death of any market it touches.

The future of venture capital has to involve greater transparency and stronger standards, to rebuild relationships with LPs, enhance market efficiency and access to liquidity. That vision requires the careful consideration of incentives, built on a fair and rational approach to understanding the value of venture investments. It means eliminating trust from the equation.

Leave a Reply