While GenAI can improve worker efficiency, it can inhibit critical engagement with work and can potentially lead to long-term overreliance on the tool and diminished skill for independent problem-solving. Higher confidence in GenAI’s ability to perform a task is related to less critical thinking effort.

source: The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking

This article is broken down into five segments:

- Priorities in venture capital

- The importance of cycles

- Forcing a reset

- The ‘knowledge work’ problem

- Operating from strength

Priorities in Venture Capital

In colder markets, founders just need capital on reasonable terms, and it doesn’t really matter where it comes from. Value-add propositions and brand strength are less important; access to hot companies doesn’t move the needle as much for LPs. Instead they care more about differentiation through strategy.

In hotter markets, the opposite is true. Investors will be chasing the fastest growing companies in the most attractive categories, out on the thin ice of excess risk. LPs, sold the same dream, care only about how GPs can parlay their way into those deals. How you invest is irrelevant, what matters is your network and your brand.

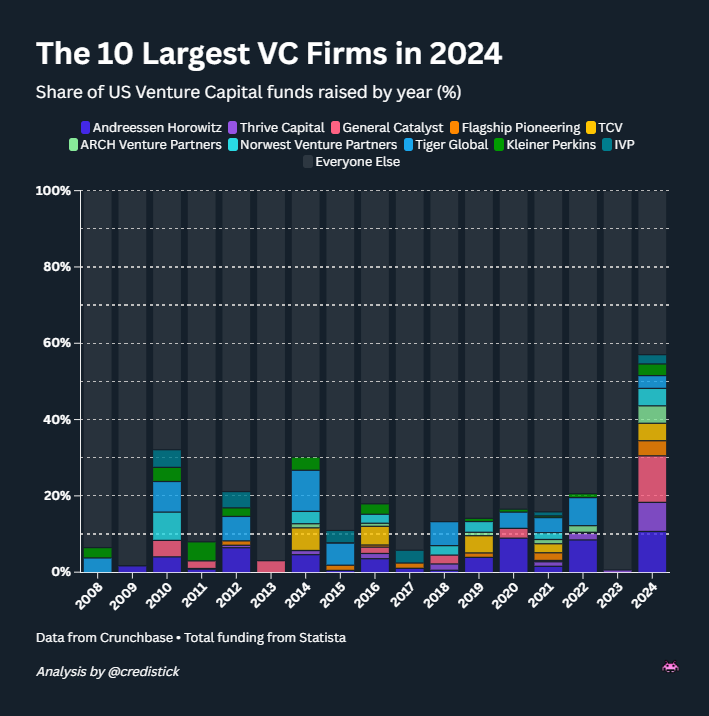

Strangely, at the peak things begin to come full circle. In 2021, when there the incredible amount of capital was spread across a record 1,594 firms, there was a horseshoe effect: with such abundant opportunity for investment, LPs and VCs once again saw the opportunity in strategy-driven alpha.

In normal circumstances, the next stage of this cycle is the crash. The firms that leaned the hardest into chasing heat would be the most exposed, with portfolios that are the most obviously out of alignment with value. What’s left are the firms who chose to focus on solid strategy, who can begin harvesting deals in the down market.

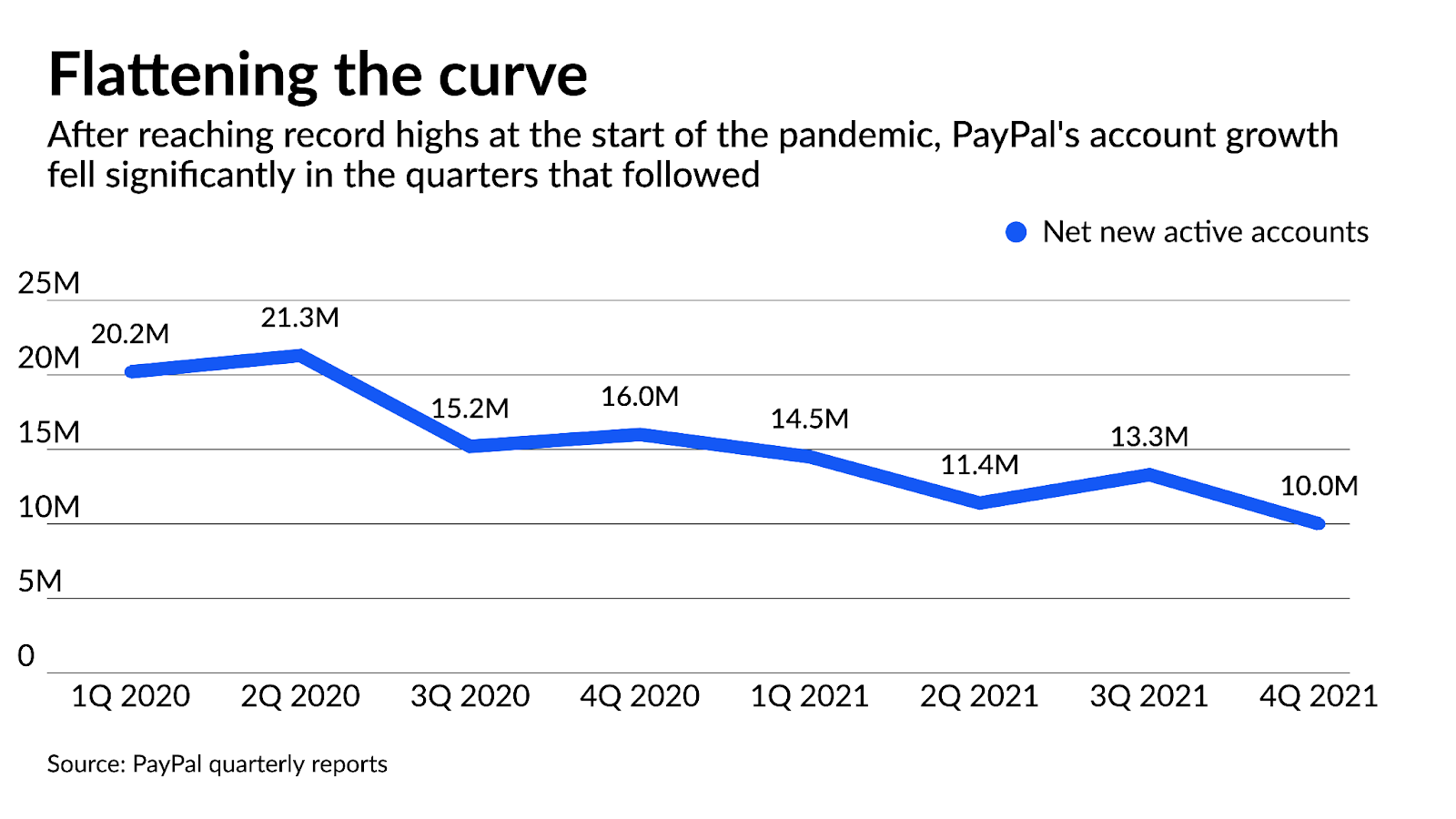

In 2022, this shift was derailed by the emergence of venture banks, designed to escape the typical cycles of venture. The largest firms raised the most capital in subsequent years. Access remained an important part of the story for LPs, especially with the convenient rise of AI.

In fact, you could argue that this was the second time that cycle was disrupted, as many experienced investors called the top in 2016-2018 only to be thwarted by COVID. Two years of intense, irrational enthusiasm for digital only exacerbated the problem.

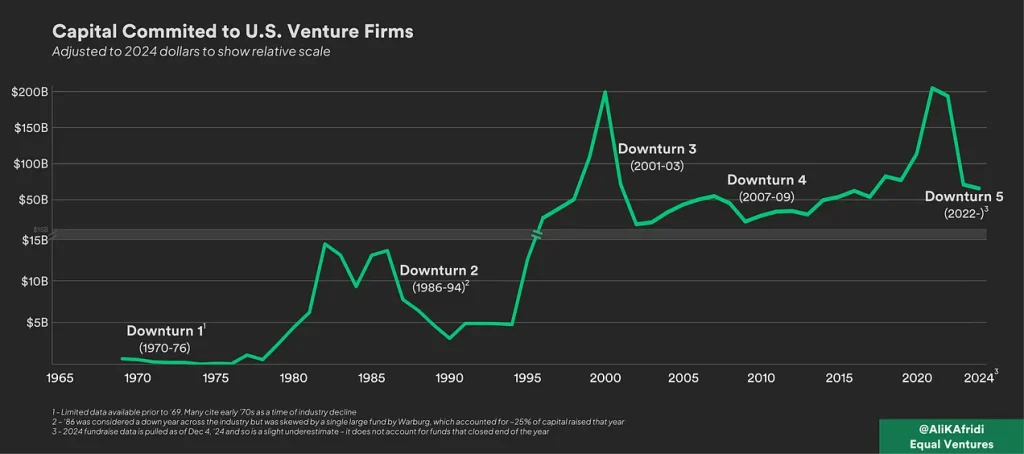

The Importance of Cycles

Consider how much of the natural world has evolved alongside fire. Wildfires serve an important purpose in preventing ecosystems from choking themselves to death on redundant biomass, and there are even species that have evolved to use fire as a mechanism to spread their seeds.

Humanities view of fire as a threat, and the goal of suppressing it entirely in the natural environment, has had disastrous consequences. We have seen the emergence of ‘mega-fires‘, where biomass accumulates to the point where spread is fierce and inevitable.

There are clear parallels here in venture. The extent to which the market is suffering today is proportional to the amount of time it took to hit a correction. What’s worse, for reasons described above we haven’t yet really allowed the full cycle to complete.

Forcing a Reset

While venture banks steam off into the distance, and venture capital tries to figure out how to navigate this environment, there are three signs of change.

- Increasingly, there’s talk of smaller LPs like family offices looking to pursue direct investing strategies. In theory, this affords them a similar level of risk with better economics, but questions remain about their bandwidth to do this properly.

- There’s been a surprising number of high profile GP departures, both launching their own funds and not. In many cases, this means partners are giving up wharever carry incentive they had. This suggests some discomfort in the status quo.

- An increasing number of founders talking about bootstrapping or ‘seedstrapping’ (one and done fundrasing), or other strategies to avoid the problems assocaited with getting on the venture capital treadmill and the expectations involved.

For the GPs that remain, it’s time to consider what the world would look like if the cycle had completed. How would they be forced to act in a truly ‘down market’ environment. Indeed, if you consider that many smaller firms have been priced out of AI, that may already feel like their reallity.

It is clear that the bar for performance is significantly higher in a cash constrained environment with higher interest rates. While that may not change the reality for venture banks, it is existential for traditional venture capital.

The ‘Knowledge Work’ Problem

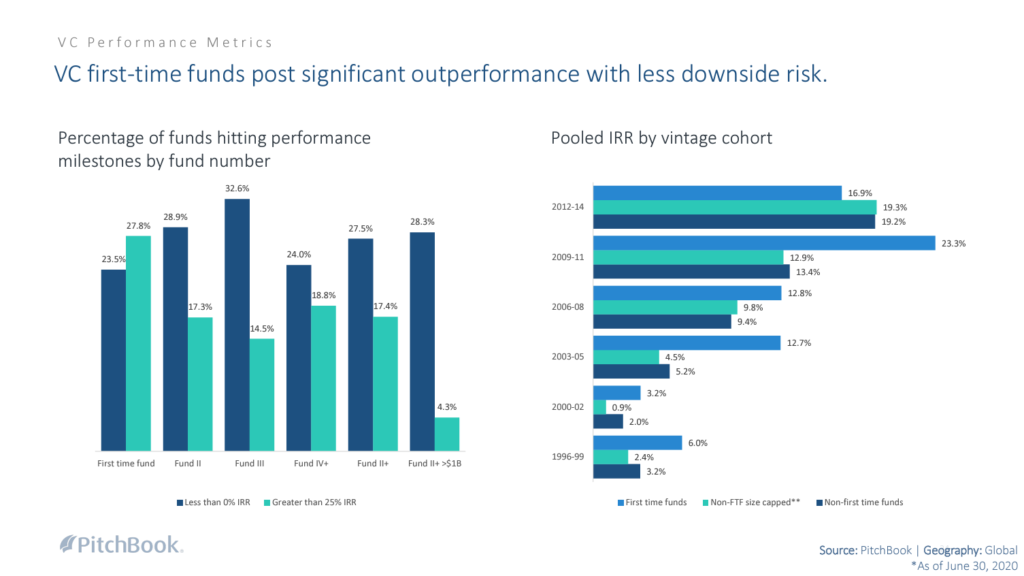

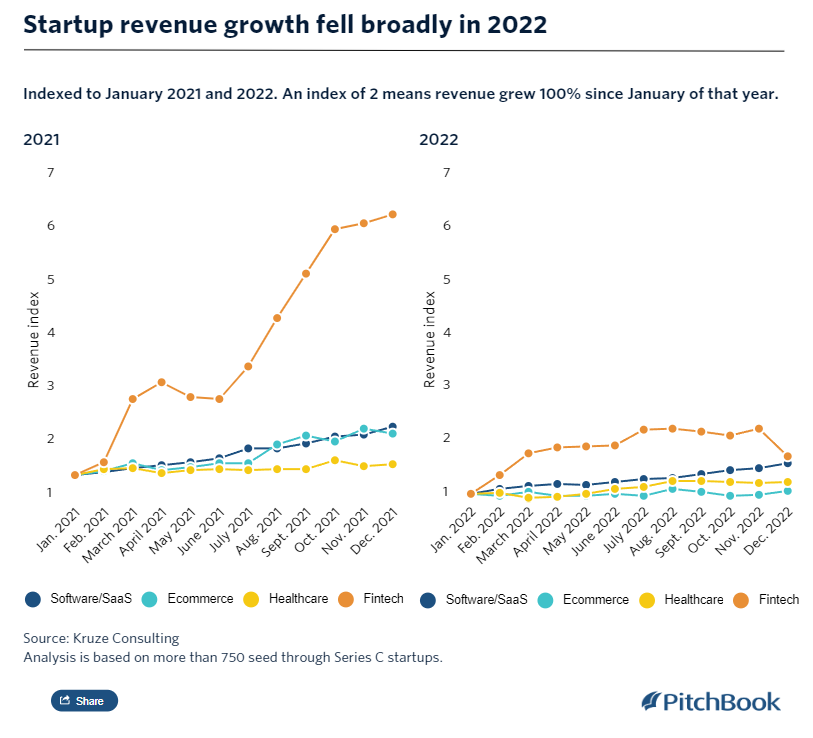

In hot markets, where investors take a prescriptive approach to investment, there is a huge problem with atrophy. Completely separate to the poor investments that come out of these periods, it’s also worth examining the practices they establish.

Investors that spend all of their time chasing hot deals based on a number of set criteria have the same basic problem as knowledge workers that rely on Generative AI solutions: they are not using their critical thinking muscles. Executing orders, not problem solving.

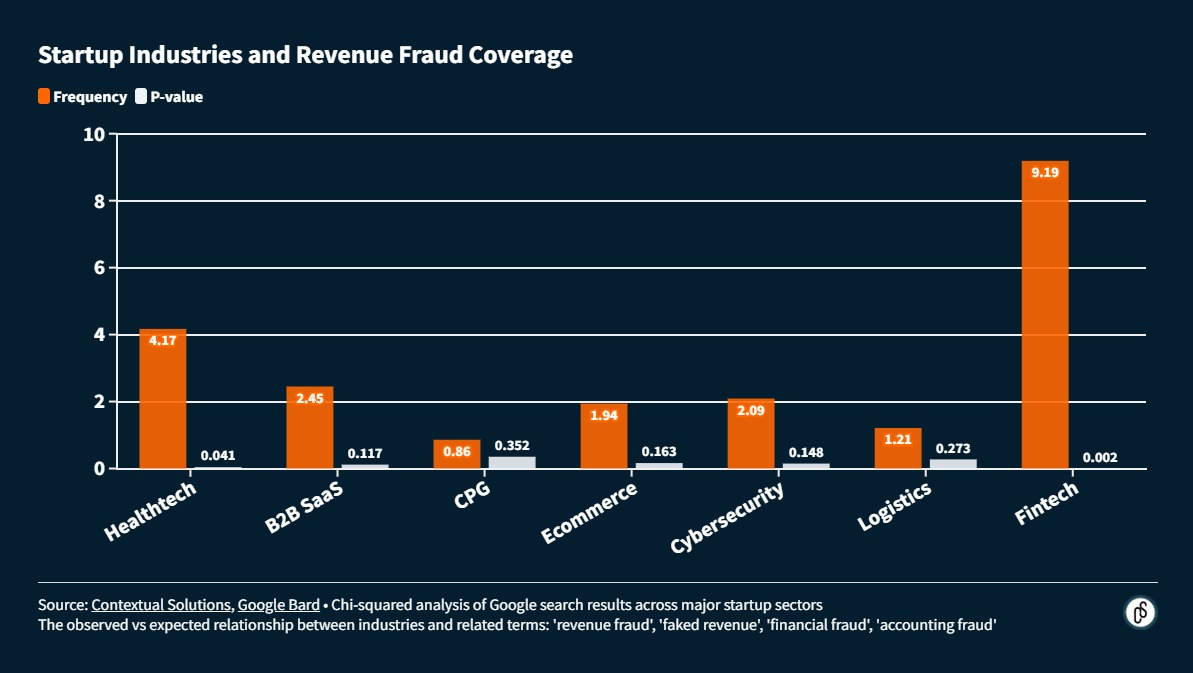

Consider how little actual thinking you have to do about an investment if your process is focused on second-order factors. Is it on an a16z market map, is it on YC’s Request for Startups, are other “tier 1” investors are in the round? Will downstream investors will give you the markups you need, and will LPs will be excited about it?

This behavior, geared towards capital velocity, is focused on second order information and pattern matching. It is a prescriptive approach that informs what gets investment, displacing the first-order considerations about things like team, opportunity, valuation, market and strategy.

This dissertation focuses exclusively on moral hazard, which refers to a venture capitalist’s propensity to exert less effort and shirk their fiduciary duties to the investors to maximize their self-interest; specifically, a VC’s propensity to choose subjective selection criteria over more cognitively taxing objective criteria when faced with multiple options and fewer resource restrictions.

“Venture Capitalists’ Decision-Making Under Changing Resource Availability”, by Noah John Pettit

While this approach might broadly work for venture banks, with an army of low-impact investors looking to index across new technology trends, it will not deliver the returns required by the traditional venture model.

Operating from Strength

The contrary to prescriptive investing is quite literally the hunt for outliers. Backing illegible companies. Being consensus averse. Resisting what have been the loudest models.

This might sound like cowboy investing. A Rick Rubin-esque vibes based approach to venture capital. It certainly can be, and if you happen to be Rick Rubin it might just work — but why take the risk?

The way for these investors to operate from a position of strength is to build process alpha. That is, do everything you can to prevent being wrong for predictable reasons (controlling for bias), and to manage the risk of being completely wrong a lot of the time (portfolio construction). Not to overintellectualise investment decisions, but to give yourself the strongest foundation to embrace the risk of uncertainty.

To take the analogy a bit further, for all that Rick Rubin is a total eccentric, guided by his own taste without the need for external validation, he is not cavalier about it. He pays immense attention to environment and routine in order to help him get the best return on his time.

There’s never a need for investors to stray from this disciplined mode of operation, it just so happens that most are prey to the cycles of venture capital and the temptation to inflate fees when opportunity arises.

Discpline is easy when opportunity is limited.