The venture capital industry, once lauded for its role in fostering innovation and technological breakthroughs, has lost its way. The pursuit of hyperscalable software companies, fueled by incentives tied to management fees and opaque valuation practices, has led VCs to prioritize short-term gains over long-term value creation.

This shift has effectively sidelined deep tech startups in favor of software ventures that, while initially promising high margins, often end up as structurally unsustainable and unattractive in the eyes of public markets and acquirers.

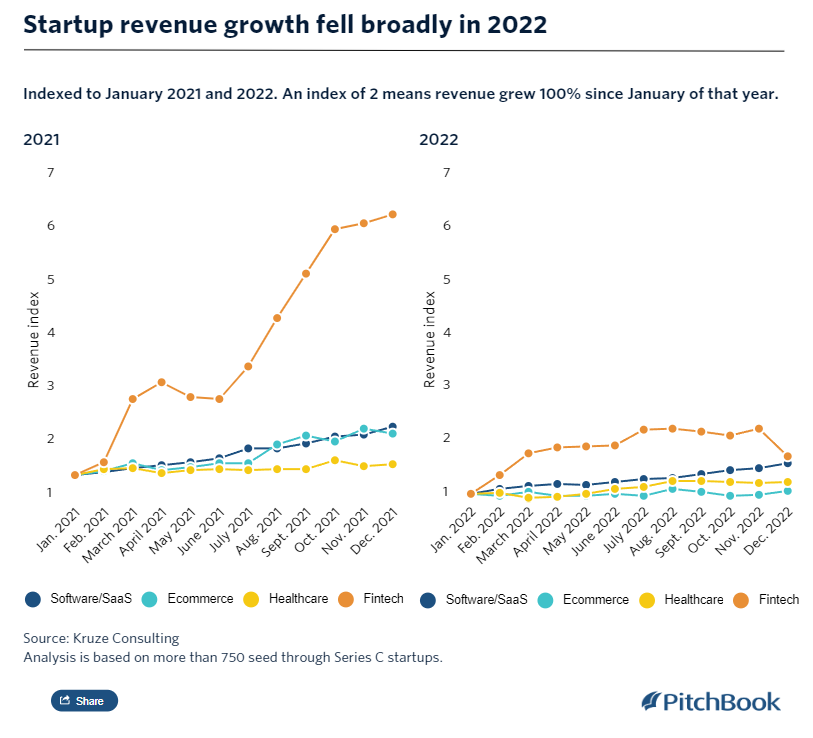

The liquidity crisis and the collapse of valuations post-2022 are, to a large extent, the result of this myopic focus.

Markups, Management Fees, and Misaligned Incentives

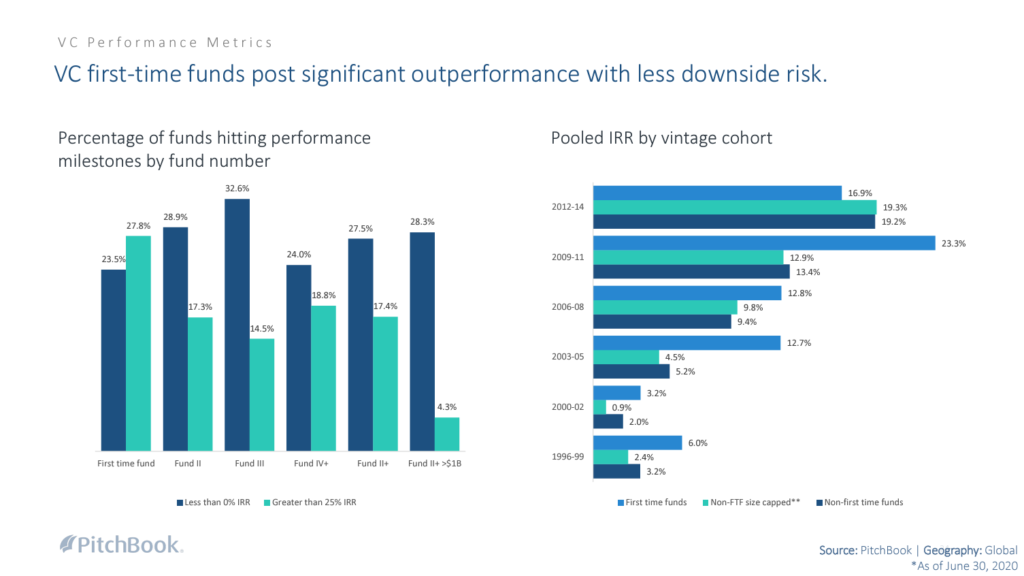

The core problem lies in how venture capital funds are structured. Many VCs earn their income primarily through management fees, which are a percentage of the assets under management (AUM). In this framework, VCs are incentivized to raise as much capital as possible and deploy it rapidly, not necessarily into companies with the strongest long-term potential, but into those that will generate high markups quickly. The logic is simple: markups create the illusion of success, which can then be showcased to Limited Partners (LPs) as evidence of strong fund performance, enabling VCs to raise subsequent funds and further increase their management fees.

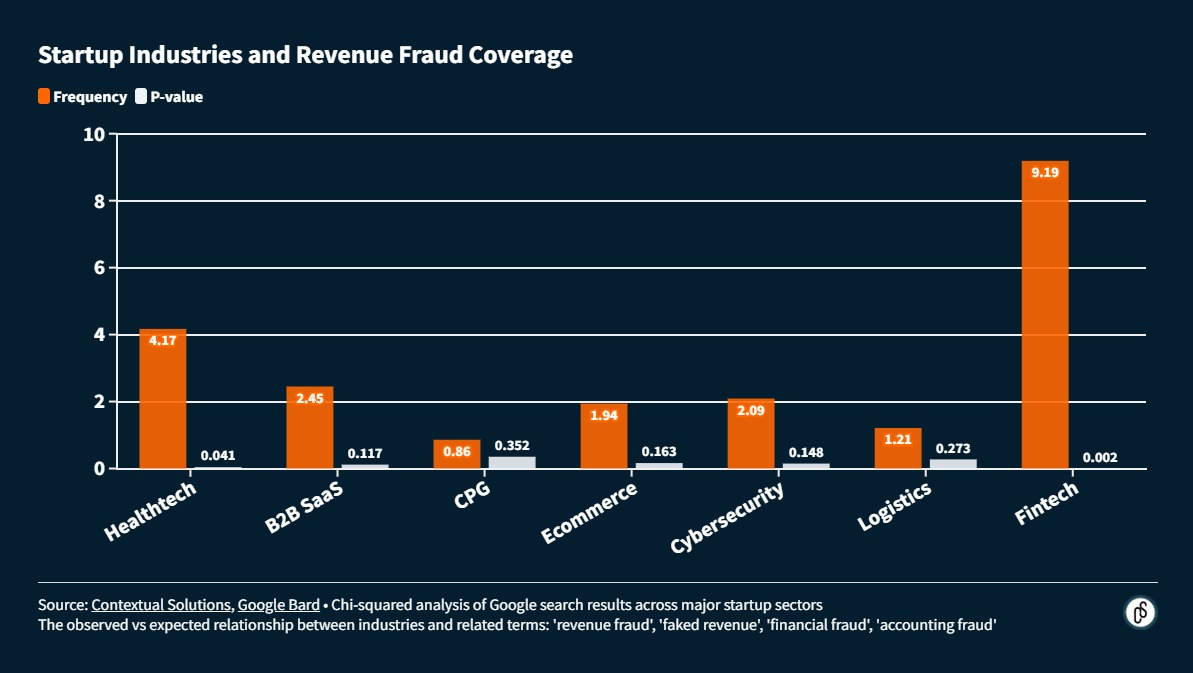

However, the criteria for these markups are alarmingly arbitrary. Without standardized metrics for valuing private companies or clear data collection methods, VCs have significant leeway to set valuations that align with their own interests. The result is an ecosystem that disproportionately rewards companies that raise as much capital as possible, at the highest valuation they can achieve, regardless of their underlying business fundamentals.

This creates a vicious cycle where capital-intensive, rapidly scaling software startups are favored over deep tech ventures. The latter, which often require years of research and development before reaching commercial viability, do not fit neatly into this model. They lack the frequent fundraising rounds that VCs rely on for quick markups and cannot be easily measured using ARR multiples which have become the venture capital industry’s (moronic) North Star.

A Crisis of Venture Capital’s Own Making

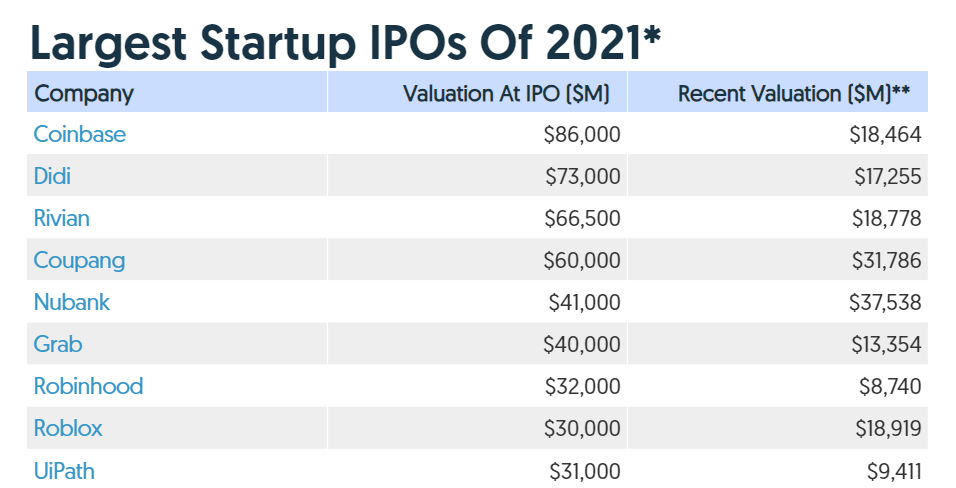

The 2022 downturn in venture-backed company valuations, especially in the SaaS sector, was a long time coming. For years, VCs funneled billions into software companies with the promise of high margins, rapid user growth, and scalable business models. But as these companies matured, the flaws in this strategy became apparent. Many of these SaaS businesses, initially rewarded for their revenue growth, began to reveal cracks in their unit economics and competitive moats.

In the public markets, where profitability, defensibility, and cash flow become the ultimate measures of value, these companies failed to meet expectations. The high-growth software playbook that worked so well in the private markets could not withstand the scrutiny of IPOs or M&A, leading to today’s slowdown in both exits and later stage valuations.

The outcome? VCs are now sitting on portfolios filled with overvalued, underperforming software companies. The lack of attractive exit opportunities has created a liquidity crisis, trapping capital in companies that may never deliver the returns expected.

The Opportunity Cost

Amidst this frenzy for rapid scaling and quick markups, deep tech has been left behind. Yet, ironically, it is these deep tech companies—whether in biotech, space tech, or hardware—that have the potential to deliver outsized returns and societal impact. Unlike SaaS companies that can be replicated with relative ease, deep tech ventures are built on defensible intellectual property, technological breakthroughs, and years of research. Their competitive moats, while difficult to establish, are significantly harder to erode.

Deep tech is fundamentally misaligned with the current VC incentive structure.1 These startups will take much longer to mature. They may not need to raise subsequent rounds until they have proven their solution, which may mean lengthy R&D cycles without easily measurable increase in value. This means fewer markups, less frequent fundraising, and, consequently, less “performance” to show to LPs.

The paradox is that while deep tech may not deliver immediate returns, its potential for outsized impact—both in terms of financial returns and societal benefits—is far greater than the current crop of SaaS investments. If successful, deep tech companies can redefine industries, create entirely new markets, and generate returns that are an order of magnitude higher than those seen in the overfunded software space.

The Return to Venture Capital’s Roots

The original mission of venture capital was to take on the risk of funding transformative technologies that traditional finance would not touch. Semiconductors, biotech, and early internet technologies were all enabled by patient capital willing to bet on the future. However, over the past decade, this ethos has been replaced by a focus on capital velocity, management fees, and the illusion of quick wins.

The solution to the current crisis is not simply more capital or better timing. It requires a fundamental realignment of venture capital with its original purpose. This means rethinking how funds are structured, how incentives are aligned, and how performance is measured. VCs need to shift away from the obsession with ARR multiples and markups toward a focus on genuine value creation, technological defensibility, and long-term impact.

In essence, the liquidity crunch facing the VC industry today is self-inflicted. By prioritizing short-term returns over sustainable value, VCs have created portfolios filled with fragile businesses ill-equipped for the demands of public markets. A return to deep tech, with its focus on defensible, transformative technologies, offers a path forward—not just for the VC industry but for the broader economy.

The future of venture capital should not be in chasing the next SaaS unicorn but in rediscovering the roots that built the industry: funding the innovations that will shape the next century. The hard pivot toward deep tech is not just a strategic necessity—it is a return to the true purpose of venture capital.

- While there are welcome signs of a hard tech rennaisance in places like El Segundo, it remains an uphill battle and is largely misaligned with venture capital incentives. Indeed, the fact that companies like SpaceX and Anduril had to be started by billionaires is evidence of venture capital’s failure. [↩]