The role of startup valuation in staged capital deployment

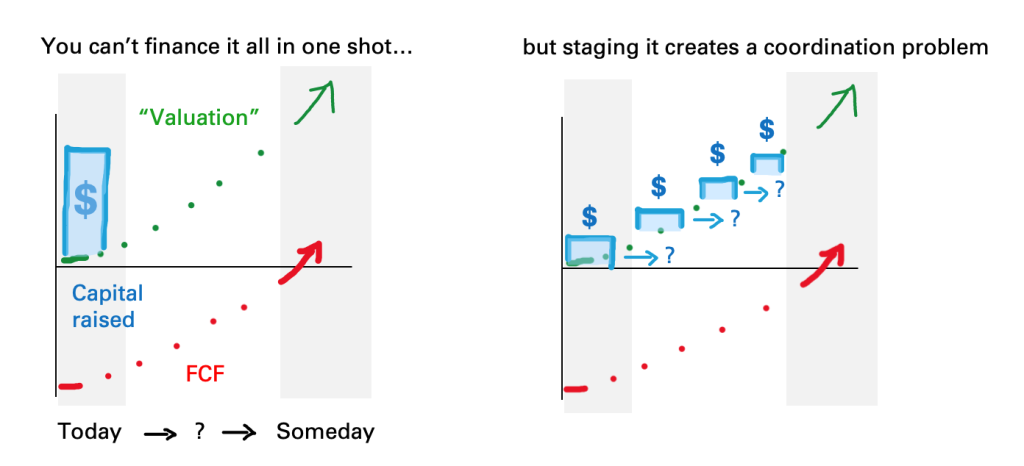

In his article VCs should play bridge, Alex Danco described the Capital Coordination problem in venture capital, created by the staged nature of investments.

I recommend reading the whole piece, but the summary is that investments are de-risked by staging capital over future milestones (with the implied valuation step-ups) rather than investing everything up-front and hoping for the best.

The heart of this strategy is the signalling game where investors offer affirmation of the investment for their capital partners.

“This gives the next investor cover to say, ok, I’ll do the same thing. I’ll invest at $20M, sending a signal: I believe that this price reflects a discount to the next round. This 20 million price, by current convention, means we believe this hand will play out as another X million in GMV run rate”, or whatever it is your signalling for this new round of bidding.”

Danco’s assessment speaks to the oddly myopic perspective of “venture math“: investors are primarily focused on understanding incremental progress (measured with ARR) rather than the ultimate outcome. This has come at a cost to sectors that are slower to start generating revenue but solve much more important problems.

He’s right to frame venture capital as collaborative (Bridge) rather than strictly adversarial (Poker), this also highlights issues like enmeshment and collusion which emerge when so much stress is put on relationship-driven outcomes over objective measurement.

The approach that Danco describes as “convention bidding” is framed as an alternative to the zero-sum attitude of formal valuation — where investors are primarily concerned with securing their own returns rather than participating in affirmative semaphore.

Indeed, this reflects a revealed preference for market signals over conviction which should trouble anyone who still believes venture capital is responsible for risk capital formation.

Discounting the Future

Further to the above, Danco’s article is a good reflection of venture capital’s poor grasp of valuation, characterised by three common misconceptions:

- Valuation is transient, and at each stage a new valuation would need to be calculated — creating uncertainty that threatens signal-driven coordination.

- Valuation is the same as price, and entry points are more a function of market norms and comps than they are of fundamental value creation.

- The practice of valuation is built on too much uncertainty to be practical for early stage companies.

While the first is inaccurate, the second is actually dangerous. The general practice of market-driven pricing has created huge structural fragility in venture capital, exacerbating the already painfully boom-and-bust nature.

The third, however, is just silly. All investments are predicated on valuation, at least in theory (the alternative being mindless momentum investing). The only difference is whether it’s written out with explicit assumptions or a mental calculation with implicit assumptions.

Indeed, valuation is essentially the story of a startup (“What happens if things go right?”) translated into numbers, with some discounting for the cost of capital and risk of failure. You can think of it as the financial source code of a pitch.

Usefully, by calculating a terminal value based on that story and discounting it using the expected rate of return in venture capital, you can also ascertain a healthy entry point for future rounds — assuming the startup remains broadly on track.

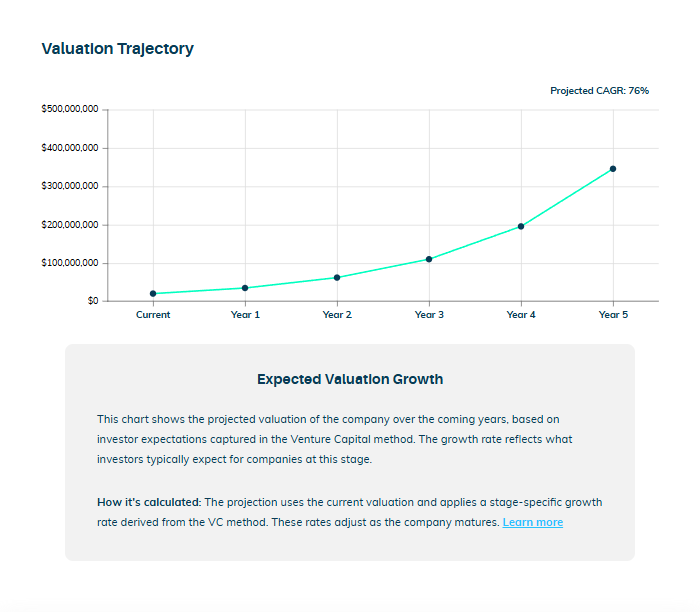

Consider the below: the valuation of a Seed round, calculated on Equidam at just over $20M. As a part of this calculation, and the future it’s predicated on, you can also see the valuation trajectory for the forecasted period. If the company raised a Series A at ~30 months, the valuation would be around $85M.

Of course, all of the usual caveats: the future is uncertain, startups pivot, markets shift. However, it’s fairly easy to built those adjustments into a model and see how they change both today’s valuation and the future trajectory.

Assessing valuation with a higher resolution view of performance enables better judgements: Perhaps top-line revenue is growing on track, but costs are surging. Maybe revenue is lagging, but margins are way better than expected.

The hope is not that forecasts play out precisely, but that they give you a useful relative perspective on performance over time.

If venture capitalists wanted a way to coordinate staged capital in the future, to finance a company efficiently (with minimal time spent agonising over terms) while ensuring a good risk-adjusted return for all investors, this is the logical approach.

Valuation is essentially the process of aligning expectations across market participants by transparently exploring data and assumptions. Typically this occurs between buyer and seller (VC and founder) in a specific transaction, but there’s no reason why downstream capital providers couldn’t benefit from that work.

It also offers the vital benefits of helping investors better understand the value of novel innovation, and limiting exposure to systematic risk of market-based pricing — getting caught in the trap of “money chasing deals“.

(top image: “The Bulls and Bears in the Market” by William Holbrook Beard)