Relying on market efficiency while investing in idiosyncrasy

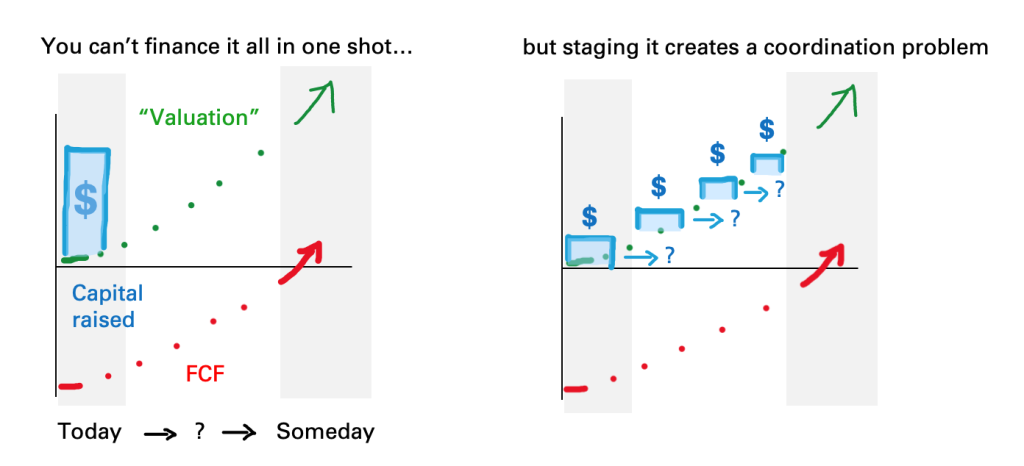

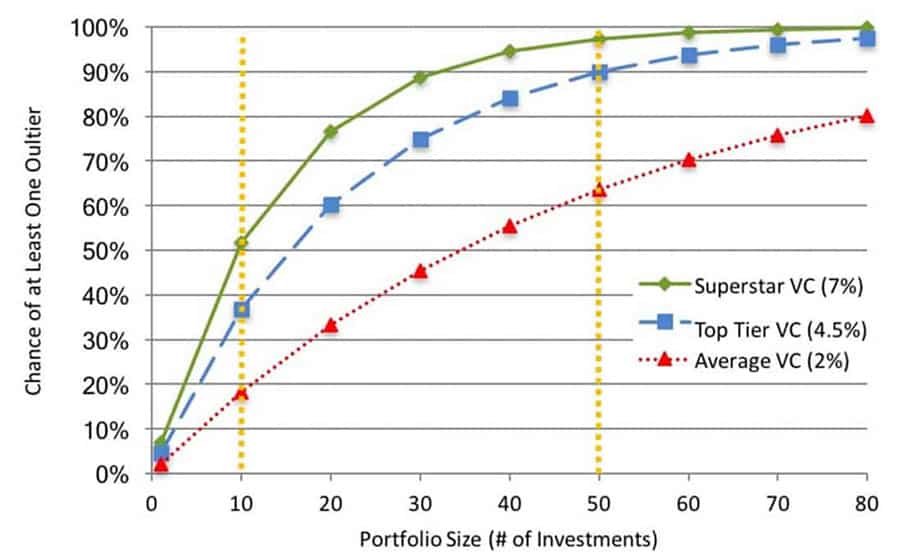

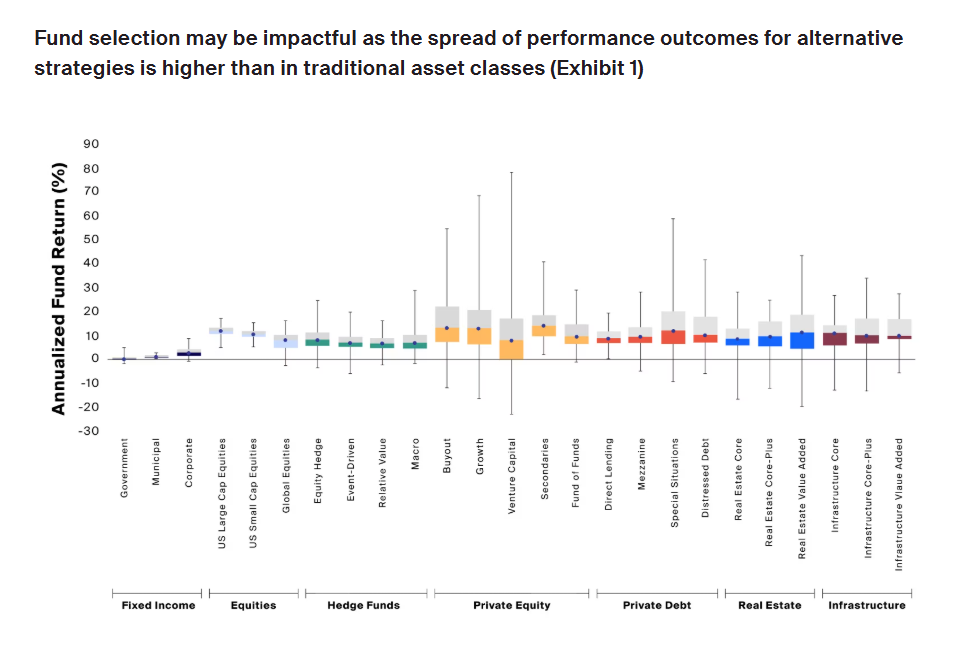

Venture capital is the hunt for outliers; ideas that are not well understood by the wider market. This strategy is rooted in the need for risk capital to finance frontier businesses.

You can see how this played out in previous generations of tech: Amazon, Airbnb, Canva, Coinbase, Dropbox, Google, Shopify, Slack, Uber… All of these companies faced an uphill battle with investor interest, and went on to produce incredible exits for the early believers. Similarly, there are many examples where the founder’s own capital paved the way: SpaceX, Tesla, Palantir, Anduril…

On the other hand, it seems relatively more difficult to find stories of competitive early rounds leading to great outcomes. Stripe, perhaps?

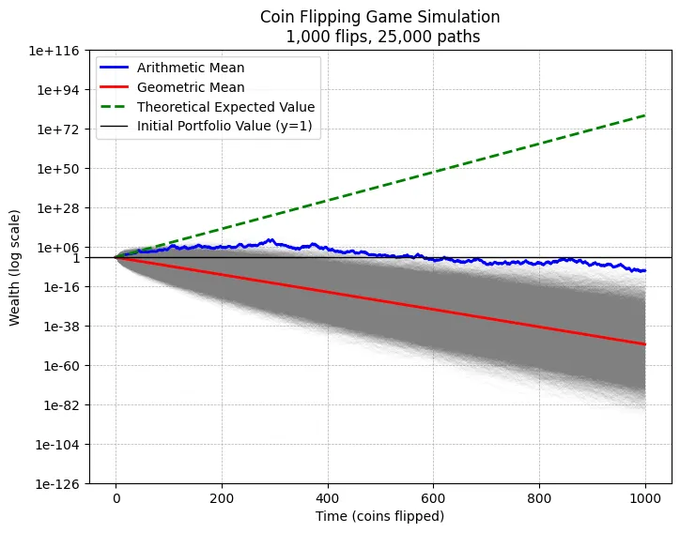

This understanding of venture capital is reinforced by the data:

We find that consensus entrants are less viable, while non-consensus entrants are more likely to prosper. Non-consensus entrepreneurs who buck the trends are most likely to stay in the market, receive funding, and ultimately go public.

The Non-consensus Entrepreneur: Organizational Responses to Vital Events

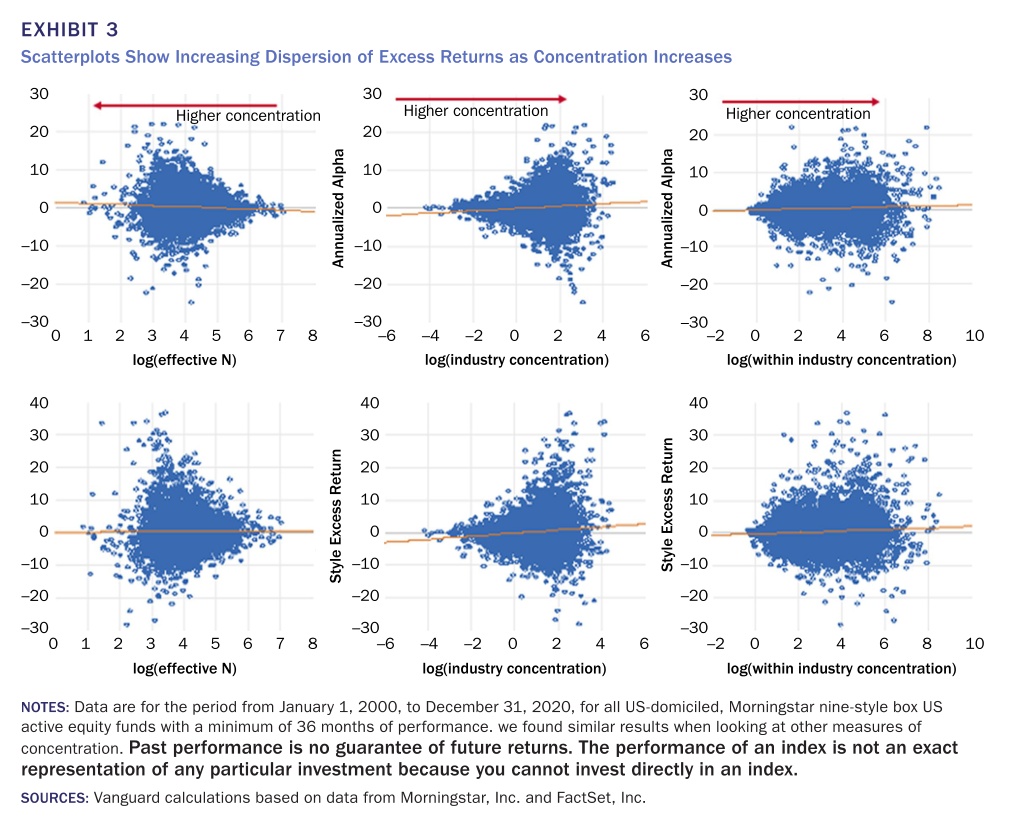

Despite this, today’s venture capitalists have an absurd reliance on the market as their lens to understand value. Herd behavior drives investor attention, and (what passes for) valuation is primarily derived from relative measures like ARR multiples.

Investors set out to generate alpha with their unique ability to recognise novel opportunities, but rely on broad market sentiment as a lens to understand what is worth pursuing.

This paradox has stumped observers.

This heavy reliance on comparable companies in the VC valuation process is perhaps unsurprising, given that relative pricing methods are not uncommon in M&A markets overall. What is less clear, however, is the exact driver behind this method, and the understanding of why a relative pricing methodology will impact startups’ valuations.

What Drives Startup Valuations?

Whether it’s marketplaces, crypto or today’s AI boom, capital herds into the category and drives up prices, and those prices then become “comps” for others.

Ultimately, the surge in deals creates a greater volume of market data for that category, reducing information friction for investment, allowing for more deals to be made more quickly. This compounding influence quickly overheats activity.

In addition to competition driving up prices and compressing due diligence timelines, there’s a further pernicious consequence: while information friction is reduced around the consensus, it is increased elsewhere.

Founders building truly innovative products find themselves facing a wall of blank-faced investors programmed with category multiples. The difficulty of raising capital becomes so great that many simply reorient their ambition to lower quality projects closer to the experience of venture capitalists. This is clearly a fundamental failure:

Information frictions in valuation can lead startups to select projects that align with the expertise of potential venture capital (VC) investors, a strategy I refer to as catering […] where a startup trades off project quality with the informational benefits of catering.

Startup Catering to Venture Capitalists

Fundamental Value

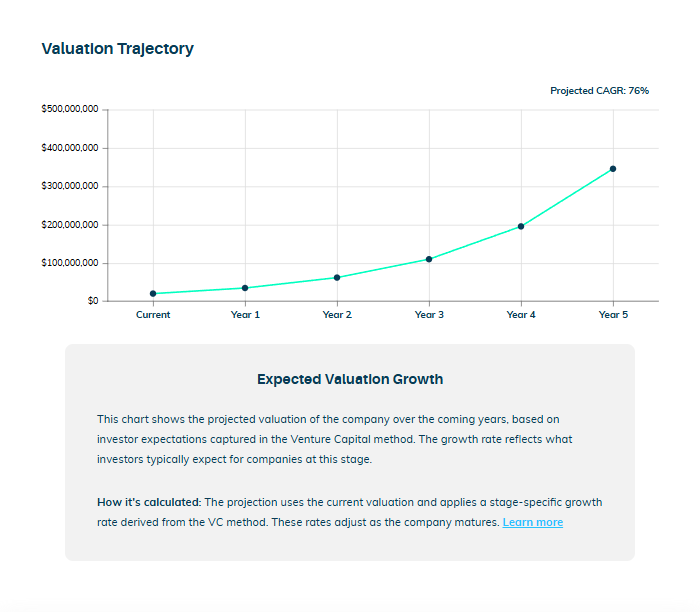

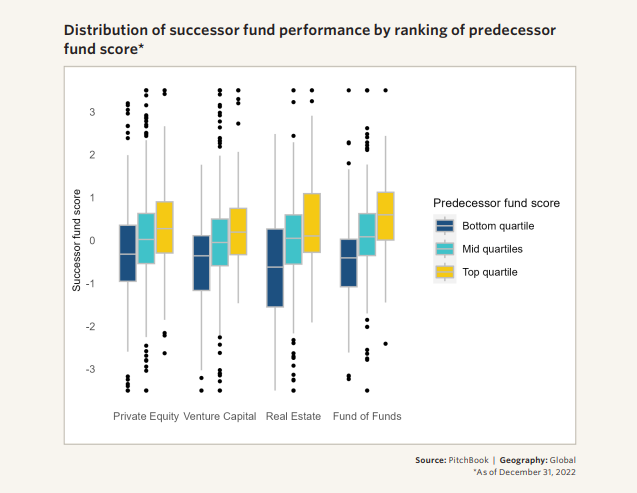

If all of this was to hold true, we should see an increase in performance by the few VCs that maintain a lens on fundamental (rather than relative) value. In theory, these investors would be better able to recognise outlier value and unique opportunities.

Indeed, that does appear to be the case. Multiple studies on venture capital investment performance and decision making processes have reached the conclusion that VCs would benefit from a better understanding of fundamental value:

Venture capital funds who base their investment strategy on fundamental values and a long-term view seem to have a measurable advantage over those who engage in subjective short-term trading strategies.”

How Fundamental are Fundamental Values?

Ideally, a startup would combine a full fledged fundamental cash flow-based approach with a thorough comparable companies analysis to cover both its intrinsic value and a market-based measure.

What Drives Startup Valuations?

So, the paradox is laid bare and the remaining question is why this is the case. There are two potential explanations:

- VCs do not understand valuation. A decade of ZIRP-fuelled spreadsheet investing has destroyed the institutional understanding of risk and the purpose of venture capital.

- There are other incentives at work which explain this phenomenon; reasons why VCs would be reluctant to closely analyse fundamental value.

Explanation 1: Hanlon’s Razor

Unsurprisingly, there’s plenty of evidence to make the case that this is unintentional; a result of simple incompetence and herd behavior. Indeed, herding is a well-studied phenomenon in professional investment, particularly when insecurity is high:

Under certain circumstances, managers simply mimic the investment decisions of other managers, ignoring substantive private information. Although this behavior is inefficient from a social standpoint, it can be rational from the perspective of managers who are concerned about their reputations in the labor market.

Herd Behavior and Investment

Chronic groupthink, and the atrophy of independent reasoning, further explains why VCs are also often unable to clearly articulate the process that goes into their investment decisions:

The findings suggest that VCs are not good at introspecting about their own decision process. […] This lack of systematic understanding impedes learning. VCs cannot make accurate adjustments to their evaluation process if they do not truly understand it. Therefore, VCs may suffer from a systematic bias that impedes the performance of their investment portfolio.

A lack of insight: do venture capitalists really understand their own decision process?

Many VCs have simply emulated the practices of their peers without fully understanding why. Indeed, those peers probably couldn’t provide a rationale either. It’s an industry of investors copying each other’s homework while pretending to be original thinkers.

Action without understanding purpose naturally erodes standards. Not only does this make VCs bad fiduciaries, it also precludes any learning and institutional development.

Almost half of the VCs, particularly the early-stage, IT, and smaller VCs, admit to often making gut investment decisions. We also asked respondents whether they quantitatively analyze their past investment decisions and performance. This is very uncommon, with only one out of ten VCs doing so.

How Do Venture Capitalists Make Decisions?

Explanation 2: cui bono?

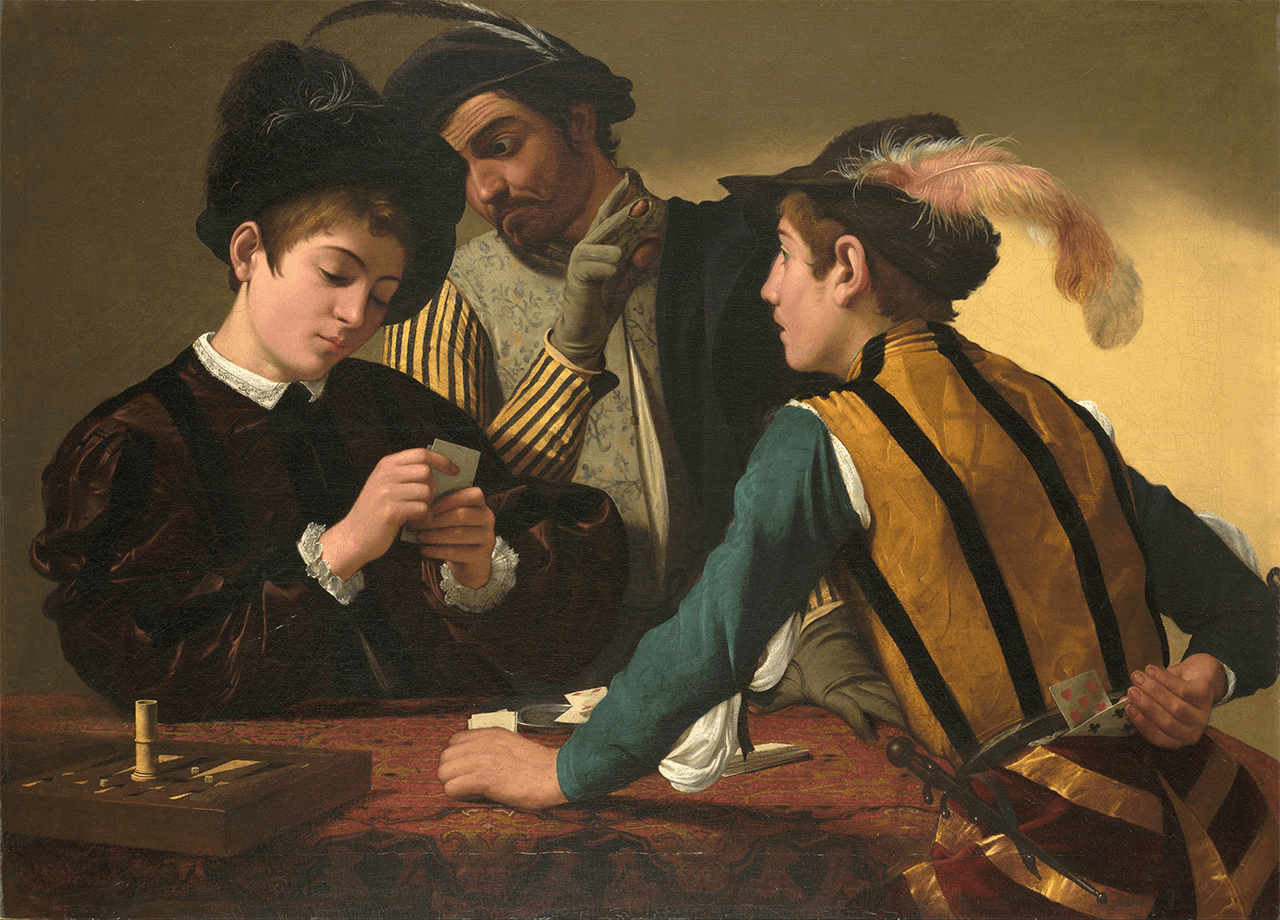

The alternate theory is that there may be some genuine motive for VCs to avoid looking too carefully at fundamental value. That somehow they are able to profit from a reality in which it is not an important driver of activity.

Perhaps it is simply because today’s VCs behave more like traders, rather than investors. That the easier opportunity is to glom onto hot categories and ride the exuberance to an overpriced exit somewhere down the line, rather than trying to find good investments.

This is also not an original accusation:

For those who are holding on to the belief that venture capitalists are the last bastion of smart money, it is time to let go. While there are a few exceptions, venture capitalists for the most part are traders on steroids, riding the momentum train, and being ridden over by it, when it turns.

Putting the (Insta)cart before the Grocery (horse): A COVID Favorite’s Reality Check!

Venture capital, as a discipline, runs an existential risk of invalidating itself by becoming institutionally what crypto is colloquially. If venture capital is just about “[creating] the impression [of] recoupment”, then its no better than the pump and dumps of the crypto bros.

Institutionalized Belief In The Greater Fool

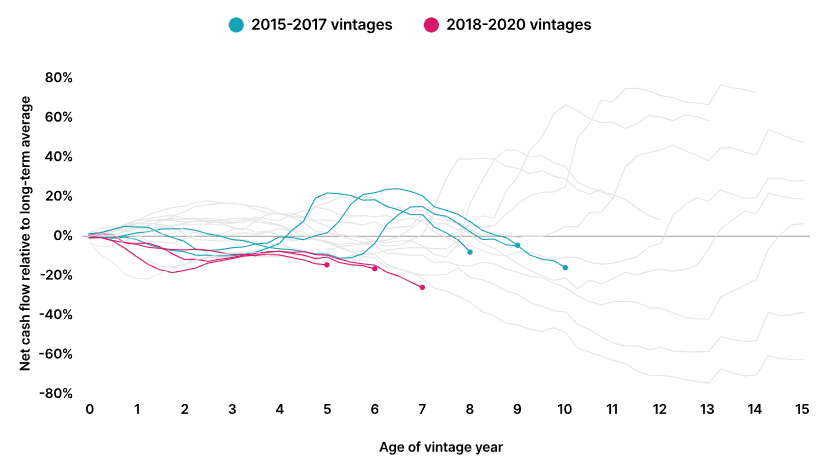

Yet again, there’s evidence that this is the case.

VCs are heavily influenced by market conditions, optimism and FOMO. None of these are original accusations, although it might be interesting to learn this has been demonstrated in research:

The optimistic market sentiments and fears of missing out in hot markets can significantly shift VCs’ attention towards cheap talk, such as promises of high growth. Such conditions may even prompt VCs to neglect costly signals such as the profitability of new ventures.

Venture Capitalists’ Decision Making in Hot and Cold Markets: The Effect of Signals and Cheap Talk

This is confirmed by research looking at this question from the other side, where it is demonstrated that VCs are commensurately less likely to herd in periods with greater uncertainty and less optimistic momentum to channel capital:

The study finds a significant negative relationship between economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and herding behavior, indicating that venture capitalists are more likely to make independent judgments when EPU rises.

Economic policy uncertainty and herding behavior in venture capital market: Evidence from China

Even when a VC talks about wanting to find category winners, they are also implicitly talking about riding a category. Were they hunting for genuine outliers, the category wouldn’t matter. There is a reason, for example, why some VCs widely publicise the categories they invest in as great opportunities, and others choose to keep any alpha for themselves.

The final reason is simple: subjective, market-based pricing is opaque and open to manipulation. VCs can collectively produce and support higher marks regardless of underlying value. They can also choose to be “opportunistically optimistic” about a portfolio company:

During fundraising periods the valuations tend to be inflated compared to other periods in the life of the fund. This has large effects on reported interim performance measures that appear in fundraising documents. We find a distinctive pattern of abnormal valuations which matches quite closely the period up to the first close of the follow on fund. It is hard to rationalize the pattern we observe except as a positive bias in valuation during fundraising.

How Fair are the Valuations of Private Equity Funds?

Indeed, much of the fallout post-2022 involved LPs feeling fairly miffed that managers weren’t being honest about underlying portfolio company value. As long as VCs broadly maintained marks, there was still hope to raise another fund on those mostly meaningless proxy metrics of performance.

In Conclusion,

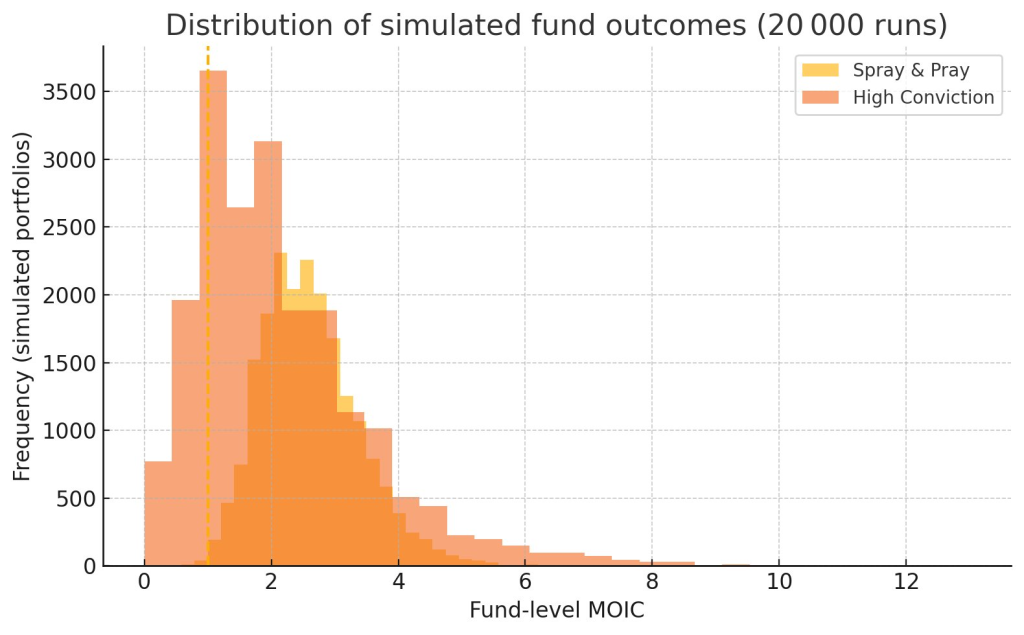

- Many VCs choose to play a short-term trading game

By focusing on market momentum, rather than companies, through relative valuation methods, VCs operate more like traders.

- Most VCs take the path of least resistance when adopting practices

While analysing fundamental value offers outperformance, relative value is easier to understand and offers strategic advantages.

Most VCs identify as investors, and some of them still are. Mostly the smaller, boutique firms who were quick to realise that they could not compete in consensus categories against the multi-stage platforms.

There is value in being a trader if you have multi-billion dollar funds and can both manifest and then coast on the beta of technology markets. They behave like market makers on the way up, extracting opportunistic liquidity, and can aim to concentrate resources into the handfull of winners before the market turns.

This strategy is toxic to smaller investors, many of whom are simply washed out in the boom-and-bust cycles that this amplifies. Instead, these investors, focused on identifying true outliers, need to consider polishing their lens on fundamental value.

(top image: Ascending and Descending by M.C. Escher)